If thou art asked in the spirit-land

To recite thy genealogy

Thou shalt reply

I am but a child

A child of little knowledge

Yet this have I heard

Tainui, Te Arawa, Mataatua

Kurahaupo and Tokomaru

These were the canoes of my ancestors

In which they paddled

Across the Great Ocean of Kiwa

Stretched before them.

Ngāti Raukawa chant, cited in Ranginui Walker, Ka whawahi tonu mātou: struggle without end

As Aotearoa New Zealand is a group of islands in the vast Pacific Ocean, the topic of waka is a poignant and obvious place to begin exploring aspects of our history. In the preface to her book Tears of Rangi, Anne Salmond emphasises the dominance of Tangaroa and the intimate relationship people of the Pacific have with the sea:

Marbled by drifts of cloud, the Pacific covers almost a third of the earth’s surface… The ancestors of Māori invented blue-water sailing… Their explosive migrations … were made possible by a navigation system based on deep knowledge of the sea. (p. 1)

The relationship between land and sea is full of stories, and like the moving tide there are many points of entry. What follows are some possible approaches teachers could take to connect the ocean with Aotearoa New Zealand’s history. While the contexts and resources offered here are intended to be accessible for all year levels, the activities will need to be adjusted depending on the nature of the class. For Years 9 and 10, other curriculum areas beyond the social sciences could be integrated: outdoor education (waka ama), and art, technology and design.

Begin with self

One approach to teaching history is to start with the specific before moving outwards.

Pepeha is an obvious launching point in kura kaupapa, but for mainstream schools this approach is new. For some people waka are a marker of identity, with ko __________ te waka navigating an ocean of whakapapa. For others, whakapapa is hazy. For example, I know some of the names of my ancestors’ ships, but beyond that I have much to learn.

- Family history can also be challenging and for some students this work may be traumatic. Russell Bishop and Ted Glynn’s work offers principles for inclusion.

- We can’t generalise about how connected each of us is to our whakapapa.

- Researching themselves, their ancestors, and their community is a way for students to start practising history.

- Interviewing older folk (in one’s family or community) allows students to feel invested in the narrative. The question, tell me about your childhood, can elicit stories that connect to events, concepts and historical trends. Linda Tuhiwai Smith says, ‘The story and the story teller both serve to connect the past with the future, one generation with the other.’

- Te Takanga o te Wā (Māori History Guidelines Year 1–8) is an excellent resource that supports teachers to approach history from a te ao Māori perspective. The Whakapapa section has a list of interview questions students can use/adapt.

- The Tuia Mātauranga programme suggests the following structure for developing and sharing family stories: Discuss your family history Identify the stories in your family Organise to share these stories amongst family, friends, or as part of a community event Make a record of the stories – a story could be written down or captured in a small video, whatever you decide best captures the story for future generations; and Share your stories with your family, your friends, and possibly at your local library.

- See here for a thorough guide on conducting oral history, including ideas around equipment, preparation, the interview, and processing the interview.

Pacific navigation

Tanenuiarangi Manawatu Incorporated

The Kurahaupō, one of the early voyaging waka, arriving in Aotearoa, together with a taniwha which guided it. This mural is in front of the meeting house on Te Hotu Manawa o Rangitāne marae and could be compared with Charles Goldie and Louis J. Steele’s imagining of the arrival of Māori in Aotearoa.

The Ngāti Raukawa chant at the beginning of this article illustrates the potency of ancestral waka as symbols of ‘tribal identity, mana and territory’ (Ranginui Walker). The power of waka in shaping identity can be seen with Ngātaroirangi, the tohunga priest who was kidnapped and taken to Aotearoa onboard the Te Arawa waka. When he tried to reunite with his Tainui people, he was told by Hoturoa, the captain of the Tainui waka, that after travelling on board their waka he was now considered one of Te Arawa.

There are many excellent online resources that can be used to explore the history of Pacific navigation:

- The He Whenua Rangatira video map beautifully captures the movement and spread of Polynesian voyagers who used the ocean as their highway. Students could work in groups to find out more about these waka – people on board, places visited, iwi links, associated whakataukī, waiata and carvings.

- The NZHistory Encounters page and the Te Ara Pacific Migrations and Canoe Traditions page have a range of information (including audiovisual material) that teachers can use to build content and generate activities.

- He Kōrero Pūrākau Mo Ngā Taunahanahatanga a Ngā Tūpuna/Place Names of the Ancestors, A Māori Oral History Atlas is a great resource for those seeking information and stories about Māori navigation and navigators. It includes maps and explanations about place names. Download the complete pdf

- The National Library has a tremendous amount of content, including images and videos. See here.

- Tuia Matauranga has a voyaging section that includes a range of conceptual understandings and inquiry questions for further exploration in this area.

- Hemi Bradford likens Māori urbanisation in the 20th century to a ‘second great migration’. His history explores changing Māori identity.

- Video about the revival of waka building by E-Tangata.

Pākehā / Tau iwi migration

‘For whosoever commands the sea commands the trade; whosoever commands the trade of the world commands the riches of the world, and consequently the world itself.’

Sir Walter Raleigh, c. 1552–1618.

I would use this quote with my senior history class when analysing the forces involved in British colonisation. It offers insight into how a small island in the Atlantic came to rule the largest empire the world has ever seen. Raleigh’s quote exemplifies an ideology of expansion, control and domination. Mercantilism was the dominant economic model of the time and this fuelled the race to seize resources from around the globe. But underpinning this empire was ship technology and sea power (‘Whosoever commands the sea…’).

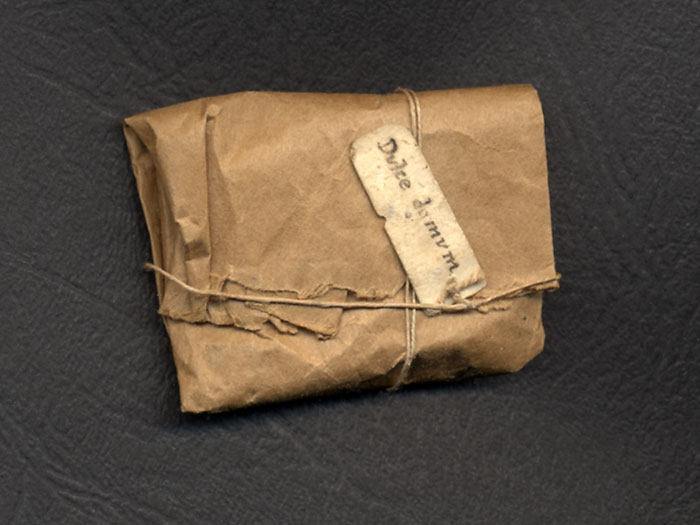

This small packet of English soil was brought to New Zealand in 1877 by Arthur Swarbrick and his younger brother, Harry. It carries the Latin inscription ‘dulce domum’ (sweet home).

‘If it were possible to condense all New Zealand’s early history into one word, it would certainly be the word “SHIPS”, for there is assuredly no country whose beginnings have been so closely associated with ships as our own.’ So begins Fanny Irvine-Smith’s The streets of my city: Wellington New Zealand, first published in 1948. In Wellington, as elsewhere, street names bear the mark of settler ships and offer an opening into stories and student inquiries.

- Getting students to inquire into the street names outside their school gates is a powerful way to begin to connect them with history and colonisation.

- Voyage Out has personal stories related to tau iwi migration to Aotearoa New Zealand and is useful for students exploring perspectives and ideas around the hopes, fears and aspirations of these migrants. Consider, for example, Arthur and Harry Swarbrick, who brought with them a small package of English soil, labelled dulce domum (sweet home). Students could be asked what they would take with them on a voyage to a new country that would remind them of Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Scandinavian stories https://teara.govt.nz/en/community-contribution/4302/a-scandinavian-story

- Papers Past is a treasure trove of information. Reading diary entries or primary accounts of ships is a fascinating eye-opener and can provide opportunities for students to make critical judgments about evidence (see Legit for a framework for analysing information).

- Surprising fact: this entry is the most frequently viewed page on the nzhistory.govt.nz website.

Women and waka

History is full of silences – people, places and events that have been overlooked, forgotten, or obscured. As teachers we need to be alert to this.

The book My hand will write what my heart dictates (edited by Frances Porter and Charlotte Macdonald) challenges the primacy of male-centred history and offers instead ‘the view from the beach, and to the women and girls who stood among groups both on the sand looking from the shore, and on the deck looking towards land.’ The overarching theme that emerges from this historical study is unsettlement – the upheaval and dislocation brought about by migration and contact. This unsettlement acted upon Māori too, especially as the 19th century wore on and war and laws were used to alienate them from their whenua and tikanga. Chapter 2 of My hand will write concentrates on the hopes and fears of Pākehā women leaving home and embarking on a new venture in a distant land.

Charlotte Macdonald offers further insight into the lives of single women coming to New Zealand in the 19th century in her book, A woman of good character: single women as immigrant settlers in nineteenth-century New Zealand. Chapter 3 focuses on the voyage from Britain and explores both the excitement and the drudgery of such a trip. Trips could last between 70 and 130 days (171 in the case of the Adelaide) and the experience was, like the ocean swell, full of ups and downs.

For teachers and senior history students interested in social history and the experience of Pākehā women, these letters and diary entries are of immense value.

The Venus and Charlotte Badger

Who isn’t keen on a pirate story? Badger’s story is fascinating and sheds light on a range of ideas, such as:

- Crime and punishment in early 19th-century Britain

- The role of evidence in history

The Black Sheep podcast has an episode dedicated to looking at the life and mystery surrounding Charlotte Badger.

Ko Hūria me te kaipuke – Hūria and the shipwreck

‘Hūria and the shipwreck’ is a compelling story that has recently been published in a wonderful book called Maui’s taonga tales aimed at children aged between seven and eleven. The book, which contains a number of stories associated with taonga held in the Te Papa museum, is linked to the TV series He Paki Taonga i a Maui.

Hūria Mātenga’s dramatic efforts to save the lives of men on board the Delaware is featured in this Roadside Story.

An image of Hūria’s funeral procession illustrates the esteem in which she was held and the significance of her life to those living in the Nelson region.

A Nelson artist recently decided to paint Hūria bare-breasted, a depiction that was seen as offensive by local iwi. This depiction could be used to generate discussion with students around perspectives, artistic expression, respect and cultural appropriation.

Hūria’s direct action of bravery and strength recalls the kōrero associated with Wairaka and the Mataatua waka. Māui’s taonga tales also features Kahe te Rau-o-te-rangi, one of at least five wāhine who signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi, who was a remarkably strong swimmer. Students could be encouraged to research and present the history of someone they regard as a wāhine toa.

A conceptual/thematic approach

If one approach to teaching history is to start with the specific before moving outwards, another approach is to begin with an overarching idea before exploring that idea through specific contexts.

A conceptual approach allows students to form connections between information and ideas. The contexts and examples through which to weave concepts are important. Using waka/ships it is possible to connect concepts like voyaging, discovery, colonisation, adventure, settlement, invasion, war, resistance, and peace.

Example: Three ships that pulled the British empire into New Zealand

The Elizabeth, La Favorite, and the Tory are three ships that link to concepts such as economics, ideology, colonisation, empire, and law/lawlessness.

Note: At Year 13 history these ships can be used when analysing forces that influenced the trend of British colonisation of Aotearoa New Zealand (Achievement Standard 3.6). In this case, the concepts are simply taught as forces.

Focus question: How did the Elizabeth, La Favorite, and the Tory contribute to the British colonisation of Aotearoa New Zealand?

Key historical relationship: Causation

Ship #1: The Elizabeth 1830

Māori were protected from political ambitions across the Tasman by the British government’s lack of enthusiasm for acquiring more formal empire. But British subjects were already making their way to these islands, and the British government could not afford to ignore New Zealand entirely.

The Elizabeth Affair illustrated a major problem that was developing in Aotearoa: how would Pākehā lawbreakers be dealt with? Captain Stewart was an accessory to murder. Kai Tahu attempted to have him tried in a New South Wales court, but the court had no jurisdiction over New Zealand. This event highlighted the need to establish British law in New Zealand to cover these British subjects.

Concept: law/lawlessness

Ship #2: La Favorite 1831

The presence of the French ship La Favorite reminded Māori of earlier violent Māori–French exchanges during the visit of Marion Du Fresne. This prompted 13 Māori chiefs from the Bay of Islands to write a letter to King William IV seeking his protection. La Favorite also acted as a warning to the British that France might colonise New Zealand. There were other instances of French interest in New Zealand (e.g., Baron De Thierry and the French settlement in Akaroa). Despite their reluctance to become officially involved in New Zealand, the British Colonial Office didn’t want their rivals, the French, to take New Zealand.

Concept: empire, nationalism

Ship #3: Tory and Cuba 1840

The Tory and Cuba left England in 1839 with shiploads of surveyors and settlers. These settlers had paid a lump sum in order to migrate and have land set aside for them in Wellington. The New Zealand Company organised this systematic migration, which forced the British Colonial Office to present the Treaty of Waitangi. These settlers had no intention of living in Māori communities, which further worried the Colonial Office about potential conflict between Māori and Pākehā.

Concept: economics, ideology

Resistance and peace

The sea has been a theatre of protest in Aotearoa New Zealand. As Anne Salmond points out, ‘Protest at sea is deeply entangled with national identity, and a concern for environmental issues.’ Much is known about the Rainbow Warrior. Less well known is a ship that is bound up with the same history, HMNZS Otago. The Otago and the Rainbow Warrior connect Aotearoa with the politics of the Cold War, nuclear armament, international relations, the role of government, and the way groups and individuals respond to political and social issues. This page has links to further information that could be used to teach a topic related to this history. And this Taxonomy of Action helps students identify actions as well as think about what kinds of action they might take in response to a social/political issue.

Sea Shepherd is an organisation whose activities in sub-Antarctic waters could serve as a contemporary example that would provide students with an interesting project and could lead to questions like, how has action on the high seas evolved through time?

Economics and ethics

New Zealand is the world’s largest exporter of dairy products and sheep meat. Agriculture, forestry and fishery exports accounted for $13.5 billion in 2020.

This year the Gulf Livestock 1, travelling from Napier to China, sank with the loss of most of the 43 crew members and all of the 5800 cows on board. This disaster could be used as a way into the history of trade as well as debates around animal rights and the ethics of live exports.

A significant turning point in the history of New Zealand’s agricultural industry was the departure of the sailing ship Dunedin in 1882. The Dunedin was fitted out with a coal-powered freezing plant that allowed about 5000 carcasses to be exported. The industry grew quickly: in 1895 New Zealand exported 2.3 million sheep carcasses; in 1900, 3.3 million; and in 1910, 5.8 million.

The Dunedin made another nine voyages before disappearing in the Southern Ocean in 1890.

New Zealand in Samoa

While the landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 witnessed the birth of the Anzac legend, the first Australian–New Zealand military operation of the First World War was actually the capture of German Samoa in August 1914. New Zealand soldiers were shipped to Samoa aboard the Moeraki and Monowai. This moment extended New Zealand’s own empire in the South Pacific.

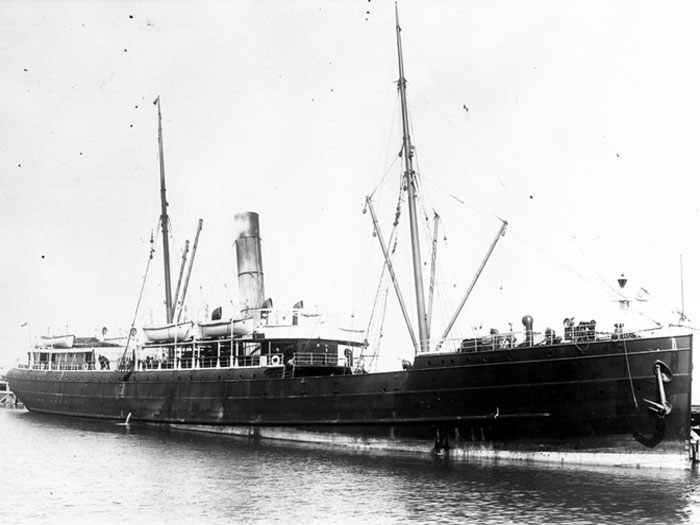

While the Monowai and Moeraki brought soldiers and administrators to Samoa, the arrival in 1918 of the Talune (pronounced ta-loon) brought sickness and death. The Tiki Lounge production 1918: Samoa and the ship of death offers the following description: The Talune is a story about ‘the deadly decision that brought death to paradise and sowed the seeds of revolution that led to independence.’ Full episode here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ohjrZjIItAw

In November 1918, Samoa’s New Zealand military administration failed to quarantine the Talune, which was carrying passengers infected with influenza. The administration also refused an offer of help from neighbouring American Samoa, which enforced a strict quarantine and escaped the pandemic unscathed. It is believed that approximately 22 per cent of the Samoan population died from the disease – a scale of loss that no other country experienced. Michael J. Field, in his influential book, Mau: Samoa’s struggle for freedom, says that ‘Politically it marked something of a turning point, for the epidemic exposed New Zealanders as bumblers and people not fit to run somebody else’s nation.'

The Mau (the Samoan nationalist movement against the New Zealand administration) arose in the wake of the influenza catastrophe. New Zealand authorities were quick to suppress this movement, culminating in what is referred to as Black Saturday, when eight peaceful demonstrators (including High Chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III) were shot dead by New Zealand forces, and as many as 50 were wounded. Field makes the point that ‘As with all colonialism, racism was at its ideological foundation. New Zealanders could not, or would not, accept that the Samoan point of view was a valid one.’ This shameful history is not well known. Tapu Misa speculates why: ‘Given our tendency to ignore history that shows us as less than heroic, it's probably not surprising that so few Kiwis know about New Zealand's administration of Samoa, from 1914 to 1961.’

There is much to learn from the Mau movement, not least of all the steadfast commitment to non-violence held by Tupua Tamasese, whose emotionally charged dying words were:

My blood has been spilt for Samoa.

I am proud to give it.

Do not dream of avenging it, as it was spilt in maintaining peace.

If I die, peace must be maintained at any price.

See the skills and historical concepts sections of the Classroom for more ideas and strategies related to teaching and learning.

Ricky Prebble, Educator–Historian

Community contributions