Place-based teaching has a lot of traction right now, and for good reason. Talking to students and their teachers about where they physically live is a great way to start an engagement with wider historical concepts and ideas.

I always begin teaching a class by asking students what they know about the name of the place I teach from — Pukeahu, the Sacred Hill. I say to the students that it is a place named by Ngāi Tara, an early iwi in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. We can then start a conversation about mana whenua over time — the genealogies and connections of people over hundreds of years who have called Pukeahu and its surrounds home. Ngāi Tara, Ngāti Ira, Ngāti Mutunga, Te Āti Awa, Taranaki Whānui o te Upoko o te Ika — all have their stories about Pukeahu, the National War Memorial Park site at Buckle St in Wellington. After European settlement, clay works reduced the height of the hill by 25 metres, but that is a story for another day.

Honiana Love’s history of Te Āti Awa tells us that her people did not ‘own’ land, but rather ‘belonged to the land’. [1] This is where the concept ‘mana whenua’ emerges from. For some students, understanding this concept requires entering the upside down, as it were. In the world view with which they have grown up, the land and the objects in it are owned by individuals. For others, belonging to the land makes perfect sense because of who they are and how they have been raised. If I can communicate a little of Te Āti Awa’s experience and relationship to the land I live and work on, spark students’ desire to learn more, to ask more, I’ll think I’ve done pretty well. However, I’m really aware of the importance of not speaking for others — I am a Pākehā educator, and I have no interest in whitesplaining. It’s important to acknowledge the limits of my experience and knowledge, and encourage students to seek out voices or reflect on their own knowledge of a place, based on their whakapapa or genealogy.

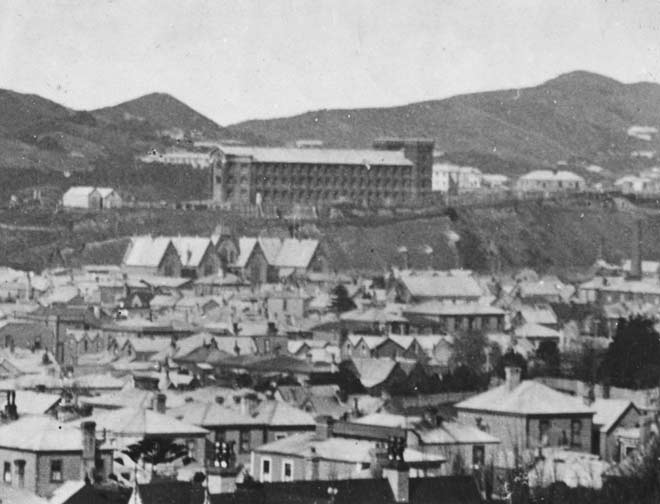

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-019606-F

Mt Cook Prison, 1896.

What else is this place called? I ask the students. Mt Cook (or Cook’s Mount as it was first called by surveyors) is something else again, and that name imposes a very different layer of ideas and values onto the site. The Deed of Settlement signed with the New Zealand Company in 1839 promising the retention of the Pukeahu site by mana whenua was undermined a year later when Lieutenant-Governor Hobson signed off on a prison for the top of the sacred hill. From that time, it was referred to as Mt Cook by the settlers who were arriving in their thousands. And, with cruel irony, it became the place where Taranaki iwi were imprisoned without trial before being sent to the South Island for protesting against land confiscation (or raupatu).

Massey University, which now sits atop the hill, has been compiling stories about Pukeahu for a number of years. These stories cover many facets of its history, and this is a great source for students’ research.

And of course discussing ‘Raupatu’ is always a good segue into a mention of Alien Weaponry’s Te Reo Māori metal track of the same name. This is, depending on the group and the aim of the lesson that day, an opportunity to introduce a discussion about the New Zealand Wars. Vincent O’Malley’s new book The New Zealand Wars: Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa (Bridget Williams Books, 2019) is a good starting point, offering area-specific descriptions of battle sites and context for discussion wherever you are in the motu.

Emma Jean Kelly

Taranaki St, Te Aro, Wellington.

Finally, I ask ‘What is the name of the street you just walked up?’, because many have come, up Taranaki St from the Gallipoli exhibition at Te Papa Tongarewa. You see lights go on in some eyes as they realise the street name still reflects the mana whenua of the area.

I still have a lot to learn about this place myself. I attended the MEANZ (Museum Educators Aotearoa New Zealand) day at Te Papa on 22 May 2019. Bianca Elkington (Te Puna Matauranga, Ngāti Toa) and Kawika Api (Pātaka Art Gallery and Museum) talked about the work they do in Porirua to ensure mana whenua voices are heard both inside and outside the museum. This includes having Ngāti Toa interns working with the current Ngāti Toa exhibition at Pātaka — if you haven’t seen it, I urge you to go.

Also at the MEANZ conference, Chris Arcus from the Ministry of Education emphasised the importance for teachers and other educators of putting Te Tiriti o Waitangi front and centre in our teaching if we want a ‘well-functioning society’ to emerge from our schools. Moving towards nuanced, educated conversations about the past is one way we can do that.

As I walked back up Taranaki St to Pukeahu, pondering how I could do better to make space for mana whenua voices in my work, I stopped to look in the shopfront which has become the Te Aro pā historical information site.

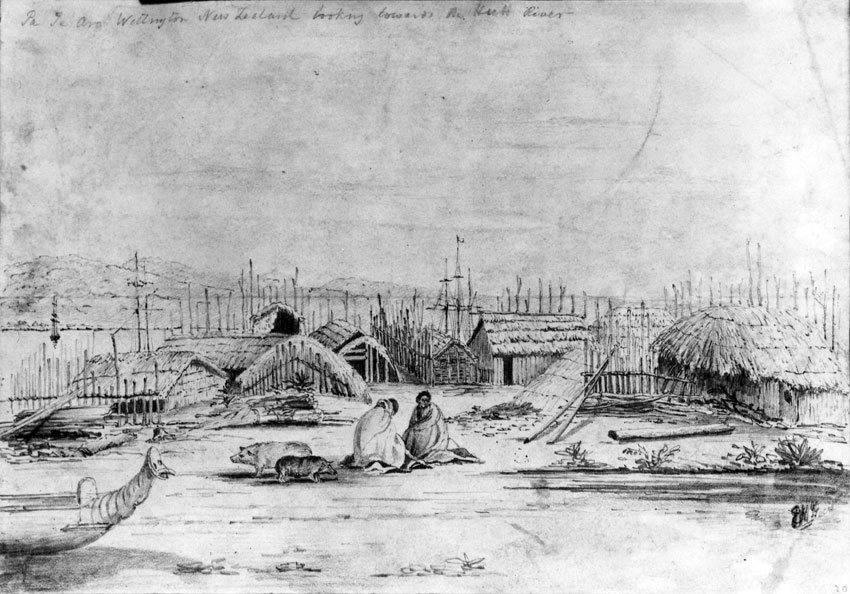

Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Aro pā historical site, Taranaki St, Wellington.

This has information about the ponga house (whare ponga) and other materials found during archaeological digs at 39 Taranaki St. They are evidence of iwi life in Te Aro and around the city before European settlers arrived. There are also layers from later European settlement to see.

Alexander Turnbull Library, A-049-001

Te Aro pā, 1840s.

In her brilliant book The Parihaka album: lest we forget (Huia Press, 2009), Rachel Buchanan has written about her feeling of connection to the Te Aro site as a Te Āti Awa woman, seeing the evidence of her people and their place in the middle of the city. As a Pākehā woman who has only lived in Wellington for a few years, I do not have the deep connections Rachel feels to that specific site, but I do feel fascinated by the evidence of past lives layered below the tarmac, and highlighted by these carefully preserved remnants of Te Aro pā. I remind myself to tell teachers about the Te Aro pā site so they can take their students to it before or after visiting Pukeahu.

Evoking the plethora of experiences and world views students bring to their learning seems central to teaching history which remembers the foundations of Te Tiriti, and also of the ground beneath our feet. Whether we are aware of it or not, the past is buried just below the surface, waiting to emerge when a new road is created, when a street name is considered, when an old story is retold.

Emma Jean Kelly, Educator

Find out more about our Pukeahu the place education programme

Notes

[1] Honiana Love, ‘Waitangi Tribunal Findings and Settlement Act’, Te Tira Whakaritorito Educating Ourselves, Book 6, pp. 2-3.

Community contributions