Using this page

This page considers who and what we remember from our colonial past by examining a range of markers that can be described as ‘sites of memory’ for this history. How relevant are these sites to contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand and our sense of identity? This place-based approach draws on stories, examples and perspectives through which students can learn about the history of their local area and of Aotearoa New Zealand. It incorporates stories from iwi and hapū about their history in their rohe.

This context for learning is in three sections:

- The purpose of such sites of memory and how they are perceived in a global context.

- The relevance of such memorials in Aotearoa New Zealand, in particular those built to commemorate colonial figures associated with the nineteenth-century New Zealand Wars.

- The ongoing relevance of place names to our colonial past.

These sections can be viewed separately or combined for a broader learning experience, as appropriate for your class and level.

Curriculum

This page supports an integrated approach to teaching the big ideas of Aotearoa New Zealand histories. It would be particularly useful for Years 7–10 exploring the context of Tūrangawaewae me te kaitiakitanga | Place and environment

Aotearoa New Zealand's Histories – Ministry of Education

Years 7–8 - Know | Aotearoa NZ's Histories – Ministry of Education

Key concepts

This page explores key historical concepts, including:

- mana (power, authority) and whenua (land)

- perspectives/points of view

- tūrangawaewae/place

- mana motuhake

- whakapapa

- historical significance

- change and continuity

- historical empathy.

Teaching ideas

Interrogating memorials and markers from our past | Te Akomanga | NZHistory – provides strategies to analyse historic sites, develop skills around perspectives, and address the big ideas of the Aotearoa New Zealand's Histories curriculum.

Joel MacManus | Where are the women? Wellington’s statues have a gender problem | Stuff – considers the masculine identity of Wellington's memorials, and is a great start for a discussion of memorialisation and identity.

What to do with markers of our colonial past?

The police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020 sparked ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests around the world. These protests highlighted the issue of systemic or institutionalised racism. Questions were asked as to why many societies, including Aotearoa New Zealand, continued to memorialise their ‘racist, imperial histories.’ From the more obvious monuments and memorials to colonial figures, to the names of our communities, schools and streets, reminders of our colonial past are all around us.

Aotearoa petition

In 2021, Te Pāti Māori launched a petition to change the country's official name to Aotearoa and officially restore the te reo Māori names for all towns, cities, and other places. Co-leader Rawiri Waititi believed there was a ‘momentum shift and a mood for change’, while asserting that ‘it's not to change who we are but I think to strengthen who we are as a nation.’ Co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer asked, ‘If not Aotearoa now, then when? When is it OK for us to be Māori and to express ourselves?’ Within two weeks, over 60,000 people had signed the petition.Reconsidering the relevance and place of monuments and place names from our colonial past challenges the very foundations of settler societies such as Aotearoa New Zealand. Some fear the adoption of a ‘cancel culture’ that tries to erase the past by judging the figures and the actions of the past by today’s standards.

Writing in 2020, Giacomo Lichtner (Victoria University of Wellington) maintained that now was not the time to ask for ‘a conversation’ about colonial statues, but a rare opportunity for action. Confronting the ongoing hurt many of our colonial statues still cause was the ‘responsibility of the descendants of those who erected them, not those who suffer because of them.’ Those opposing their removal, characterising such actions as a ‘prelude to burning books’, were in Lichtner’s eyes, wrong.

Black Lives Matter – Wikipedia

Part one: sites of memory

The American historian Jay Winter described sites of memory as places where groups of people engage in public activity to express ‘a collective shared knowledge … of the past on which a group’s sense of unity and individuality is based.’ In Realms of Memory, French historian Pierre Nora acknowledged that ‘archives, monuments and celebrations are not merely the recollections of memory but also the foundations of history’. Statues and other monuments, plaques, place names, and so on, are ‘sites of memory: places and objects through which a society decides to cast in stone (or in bronze) its collective memory’. These memories are ‘never really collective, but simply society’s preferred version of events at a given time.’ Such monuments highlight a dominant set of values and ‘enshrine these so anyone bold enough to question them or offer an alternative view, an alternative memory, might think better of it’.

Statues can reinforce community and group identity. As an art form, they may move those who look at them. Some may serve a social purpose as a place to congregate, for example, on Anzac Day. A common argument made by people supporting the retention of the more problematic memorials of the past is that we can learn from them. Others disagree. Giacomo Lichtner asserts that ‘to suggest statues are there to teach history, or that tearing them down is the prelude to burning books – as National Party MP Simeon Brown rather bizarrely suggested – is lazy. Statues do not teach; teachers teach.’

Tom Mockaitis, Professor of History at DePaul University, Chicago also maintains that ‘statues … don’t teach history. They commemorate individuals and celebrate a romanticized vision of the past. They provide neither context nor an explanation of events. They elevate representatives of some groups while ignoring others. For these reasons their place in the public sphere is highly problematic.’ Monuments and memorials create a link between three different situations: the event or person being memorialised; the building of the monument; and the ‘now’ – standing in front of the marker and ‘learning’ from it.

Jay Winter | Sites of Memory – JSTOR

Remembered Realms: Pierre Nora and French National Memory – History Cooperative

Tom Mockaitis | Statues do not teach history – The Hill

Removing memorials: international examples

United States

Black Lives Matter protestors in the United States tore down statues of Confederate leaders as well as the explorer Christopher Columbus. Pressure mounted on authorities to proactively remove monuments connected to slavery and colonialism. President Donald Trump said it was ‘sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments.’ Trump maintained that while you cannot change history, you can learn from it. He also expressed concern as to ‘where it will all end? Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson – who's next, Washington, Jefferson? So foolish!’ Virginia decided to remove its statue of Confederate general, Robert E. Lee from the US Capitol, where it had stood for more than a century, and replace it with a statue of civil rights activist Barbara Johns. Mockaitis saw this decision and the accompanying social media backlash as revealing a need to ‘consider how American history is being commemorated and taught and what, if any role, iconography should play in the process’.

Confederate and Columbus statues toppled by US protesters – BBC News

Canada

Another argument in defence of the statues and memorials of the past is that as we ‘can’t change history’, pulling them down will achieve nothing. In August 2020, activists in Montreal pulled down a statue of Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald. Remembered by some for his nation-building policies, Macdonald is remembered by others for creating the residential school system under which some 150,000 Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to state-funded boarding schools. A government report in 2015 called the practice ‘cultural genocide’. Nevertheless, key political figures were united in their opposition to the attack on the Macdonald monument. Prime minister Justin Trudeau described it as ‘vandalism.’ François Legault, the premier of Quebec, contended that in fighting racism, ‘destroying parts of our history is not the solution.’ He concluded that ‘vandalism has no place in our democracy and the statue must be restored.’ Montreal’s mayor, Valérie Plante, stressed the importance of placing problematic historical figures ‘in context’ rather than ‘simply removing them from our history.’

Trudeau condemns toppling of Canada's first PM as 'vandalism' – BBC News

Belgium

Belgian protesters defaced statues of King Leopold II due to the deadly legacy of his rule in the former colony of Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo). A Belgian of Congolese descent described how walking ‘in a city that in every corner glorifies racism and colonialism … tells me that me and my history are not valid.’ Others commented on Belgium ‘waking up from a sleep’ and facing ‘a reckoning with the past.’ A petition calling for the removal of a statue of Leopold II near the Royal Palace in Brussels received 74,000 signatures. Those opposed to these proposals defended these monuments as ‘part of our history.’

Leopold II: Belgium 'wakes up' to its bloody colonial past – BBC News

United Kingdom

Similar debate was sparked in the United Kingdom when a statue of seventeenth-century slave trader Edward Colston was pulled down and dumped in Bristol harbour in June 2020. Colston’s case was complicated for some by what they saw as the risk of judging him by today’s moral standards. His legacy can be seen on Bristol's streets and in its memorials and buildings. On his death in 1721, Colston left his considerable wealth to a range of charities, leading some to describe him as a philanthropist. Others pointed out that he had accumulated his riches as a slave trader. Home Secretary Priti Patel called the tearing down of the statue ‘utterly disgraceful’. Historian David Olusoga disagreed, believing the ‘statue should have been taken down long ago’, and observing that statues proclaim, 'this was a great man who did great things.' After a London statue of the slaver Robert Milligan was removed, mayor Sadiq Khan initiated a review of all of London’s monuments.

Edward Colston statue: Protesters tear down slave trader monument – BBC News

Sadiq Khan orders review of London’s landmarks including slave trader statues – TimeOut

Daphné Budasz approached this debate by reflecting on the relation between commemoration, national identity and the social role of history. ‘As many historians claim, statues are not history. Nor are they material sources, archaeological artefacts fortuitously preserved through time. They instead are objects of commemoration: the political constructions of certain narratives from the past, and an expression of the ruling power who decided to put them there.’ Budasz highlighted how many of the public statues under attack were from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a time when history was ‘first and foremost the story of “great men” credited for nation-building.’ They highlight the ‘notion of nation grounded in a claim of a shared past, with members allegedly connected by a common history, or, rather, by the collective memory of it.’ The memorials in question promoted a shared identity which ‘tended to exclude minority memory.’ War memorials are common examples of monuments designed to promote a ‘notion of nation grounded in a claim of a shared past. They are typically one-sided, erected by the victors to commemorate their dead. Until recent years, such as the centenary of the First World War, they have rarely mentioned or acknowledged the ‘enemy’.

Historians have long debated the appropriateness of judging past behaviour by contemporary moral standards. History Extra asked six historians whether we should judge historical figures by the morals of today. Andrew Roberts of King’s College London argued that while it is ‘completely illogical, ahistorical and unfair to natural justice to judge the people of the past by today’s morals, it is also very hard not to.’ Charlotte Riley, from the University of Southampton, said that while ‘a historian’s primary aim is rarely to make a moral balance sheet of the past’, she was ‘wary of the idea that people from the past should escape our moral judgement. Historians can never approach the past as neutral observers.’

Daphné Budasz | Colonial memory and the social role of history – EUIdeas

Should we judge historical figures by the morals of today? – History Extra

Part two: memorialising the New Zealand Wars

In Aotearoa New Zealand, much of this debate has centred on events and figures from the New Zealand Wars of the nineteenth century. What to call these conflicts, spread over time and place, has been a source of much debate. Several thousand people died in these battles, the great majority of them Māori. Their consequences, in particular the raupatu (confiscation) of significant quantities of Māori land, had a profound and long-lasting impact on Māori society and economy.

There are more than 60 memorials in Aotearoa New Zealand to the dead of the New Zealand Wars. As well as formal monuments and memorials to some of the leading colonial figures of these conflicts, other memorials take the form of the names of towns and cities and street names. Few of these names recognise or acknowledge Māori. For iwi and hapū they remain as painful reminders of hurt and loss. In considering the impact of such markers of our colonial past, it is worth asking:

- How much have we collectively thought (or cared) about such markers and their impact on people today?

- Are they to be revered or reviled; honoured or ridiculed; or co-opted for a new purpose?

- Do these markers only have the meaning people give them?

- What difference would it make to remove certain memorials or change place names?

We will examine a couple of New Zealand Wars memorials to initiate a debate about their appropriateness and ongoing relevance. Put simplistically, do such memorials do more harm than good? You may want to consider how these examples might be used as templates for inquiry into similar debates in your own rohe.

New Zealand's Internal Wars – NZHistory

Commemorating and naming the New Zealand Wars | Te Akomanga – NZHistory

Land confiscation law passed – NZHistory

New Zealand Wars memorials – NZHistory

The Nixon memorial, Ōtāhuhu

In June 2020, The Spinoff asked five New Zealanders to nominate the local monuments, statues and place names they thought should be removed. One of the suggestions was to toss the ‘Colonel Marmaduke George Nixon monument in Ōtāhuhu into the ocean’.

Of their time

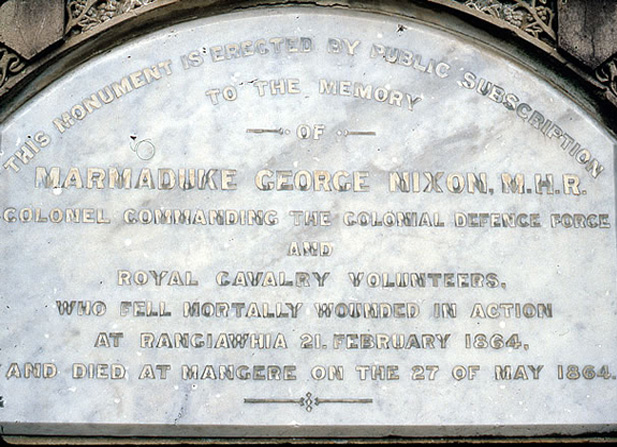

The Nixon memorial is one of three memorials erected in New Zealand during the New Zealand Wars. The others are the Moutoa memorial in Whanganui and the memorial to the 57th Regiment at Te Hēnui Cemetery in New Plymouth. These and later New Zealand Wars memorials exemplify Pierre Nora’s assertion that memorials represent society’s preferred version of events at the time they were erected. Read more about New Zealand Wars memorials.The memorial in question stands on a triangular reserve in Ōtāhuhu, at the busy junction of Mangere and Great South roads. It commemorates the Ōtāhuhu settler and Franklin Member of the House of Representatives, Colonel Marmaduke Nixon.

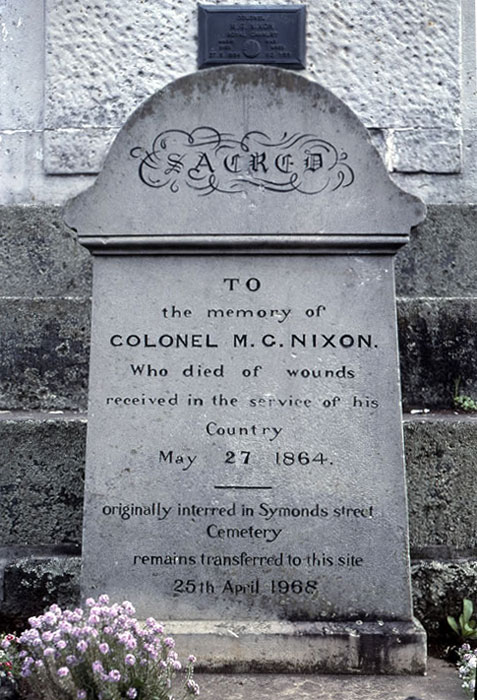

Nixon commanded the Colonial Defence Force Cavalry during the Waikato War (1863–4). He died on 27 May 1864 from a wound he had received three months earlier at Rangiaowhia. The memorial acknowledged ‘the brave men who served their Queen & Country in the Maori War, Waikato Campaign 1864’. Nixon was originally buried in Auckland’s Grafton Cemetery. His remains were transferred to the base of the memorial on Anzac Day 1968, and a headstone was erected.

In 2017, commentator, Shane Te Pou (Ngāi Tūhoe) expressed surprise ‘that modern New Zealand commemorated this guy (Nixon)’, believing his actions at Rangiaowhia made him ‘unworthy’ of such a public memorial. Given that the memorial itself had been there since 1868, it could be debated whether ‘modern’ New Zealand had commemorated Nixon or was largely oblivious as to who or what was represented by this stone obelisk. Te Pou challenged Auckland mayor Phil Goff and his council to begin a conversation about removing the Nixon memorial from its current site. While agreeing that the memorial was part of our past, Te Pou maintained that it needed ‘to be put in a museum, and we need to have a debate and discussion about it.’

‘Stop immortalising a legacy of murder’: Which NZ statues need to be toppled? – The Spinoff

Nixon memorial, Ōtāhuhu – NZHistory

Marmaduke George Nixon – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

The fight at Rangiaowhia – NZHistory

Call for Ōtāhuhu colonial leader memorial to go – RNZ

Who was Marmaduke Nixon?

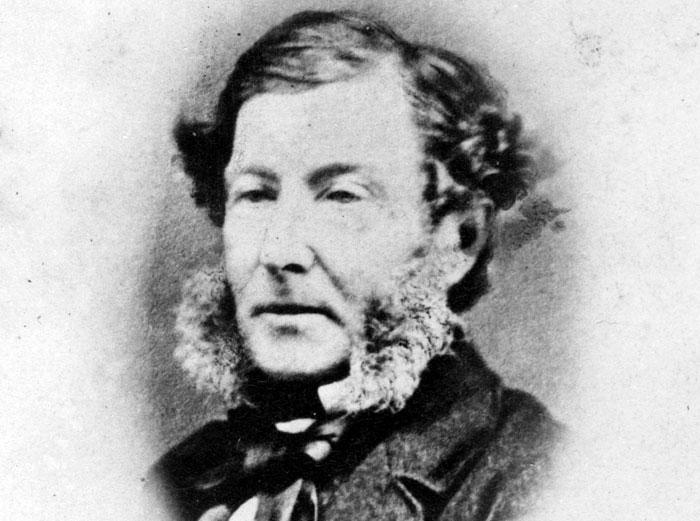

Marmaduke Nixon, a former officer with the British Army in India, arrived in New Zealand in 1852. He purchased a farm near Māngere, where he advocated for local settlers to have access to ‘waste land’ owned by Māori in the Waikato and Thames regions. When war broke out in in Taranaki in 1860, he was appointed as lieutenant colonel of the Auckland Militia and the Royal Volunteer Cavalry, who's role it was to protect the line of communications and supply between Auckland and the South Auckland redoubts and outposts. In May 1863 the Colonial Defence Force Cavalry was formed, with two troops from the Auckland district; Nixon became its commandant in June. At Otahuhu in July 1863 nearly 200 volunteers, mainly young farmers from the district formed what became known as ‘Nixon's Horse'. They joined Lieutenant General Duncan Cameron's invasion of the Waikato.

Fighting begins | War in Taranaki 1860–63 – NZHistory

The invasion continues | War in Waikato – NZHistory

What happened at Rangiaowhia?

General Cameron bypassed the Māori defensive position at Pāterangi and ordered an attack on the Kīngitanga supply base at Rangiaowhia, a kāinga near Te Awamutu. The events that unfolded on the morning of Sunday 21 February 1864 have been hotly debated by historians and the descendants of Ngāti Apakura, the primary inhabitants of the settlement.

Nixon’s Colonial Defence Force Cavalry led the assault and caught the inhabitants by surprise. They took cover in their whare and other buildings, including the village’s two churches. One cavalryman, Sergeant McHale, was shot as he advanced on a whare. His comrades, led by Nixon, attempted to recover his body while firing at the defenders. Nixon was shot during this action, suffering severe chest wounds to which he would eventually succumb on 27 May. Nixon's men dismounted and poured concentrated fire into the whare, in which defenders had gathered. After this was either set on fire deliberately or ignited by sparks from musket fire, a number of Māori who attempted to surrender or escape the flames were shot dead. The British and colonial force lost five men, either killed outright or mortally wounded. Twelve Māori men, youths and women are known to have been killed, although some estimates are higher.

Historian Vincent O’Malley described Rangiaowhia as the scene of ‘one of the most painful and contentious incidents of the Waikato War. To call the British raid on the settlement … a ‘’battle’’ would be misleading.’ Acknowledging that there are ‘multiple and often contradictory accounts’, all of which need to be carefully handled, O’Malley observed that the ‘pain and anguish caused by the British attack remains all too evident a century and a half later.’ In Voices from the New Zealand Wars, O’Malley examined first-hand accounts from Māori and Pākehā who either fought in or witnessed the New Zealand Wars. He argues that one such account of a Māori woman who ‘survived the torching of a whare karakia at Rangiaowhia’ confirms other oral histories that counter ‘a longstanding claim that it (Rangiaowhia) never happened.’ Writing in the online magazine, E-Tangata, Hazel Coromandel-Wander of Ngāti Apakura shared kōrero handed down from her great-grandmother, Te Mamae Pahi, a teenager at the time of the attack.

150th anniversary

At the 150th commemoration of Rangiaowhia, in 2014, a plaque was unveiled at the site to commemorate the events of 21 February 1864. Tom Roa (Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato) expressed the ongoing pain and grief for the local iwi, Ngāti Apakura: ‘I pāhuatia ō mātou tūpuna i Rangiaowhia – our ancestors were killed unguarded and defenceless at Rangiaowhia.’

Māori viewed the assault on Rangiaowhia as an act of treachery. Following the battle at Rangiriri in November 1863, Kīngitanga leaders had been criticised for keeping women, children, and old men inside the pā instead of sending them to a safe place. As the British invasion drove deeper into Waikato, Rangiaowhia was selected by the Kīngitanga as a place of refuge for their most vulnerable people, a decision which was conveyed to the British nine days before the eventual attack. As a consequence, O’Malley and others maintain that those killed in the attack were not victims of war but ‘non-combatants who had been brutally murdered.’

Vincent O'Malley | Remembering Rangiaowhia: 150th Anniversary – The Meeting Place Blog

Hazel Coromandel-Wander | Rangiaowhia: Voices from the embers – E-Tangata

Māori King movement origins – NZHistory

What to do about the Nixon memorial?

Shane Te Pou argued that the best way to facilitate a conversation about the role and relevance of memorials such as Marmaduke Nixon’s was to place them in a museum. But it is worth thinking about who typically visits or accesses such cultural institutions. Would relocating a memorial to a museum simply make it less accessible and therefore reduce the chances of its relevance and significance ever being critically debated? It could be argued that its current location at a busy intersection is not a convenient one either. Should we make such monuments more visible to foster discussion about them? Monuments such as this one can recede in the rear-view mirror as we navigate from point A to point B. How might we use such memorials to become more observant of our built heritage and environment?

Professor Tom Roa (Ngāti Maniapoto, Waikato) of the University of Waikato believed removing the memorial would not improve New Zealanders’ understanding of our past. Professor Paul Moon (Auckland University of Technology) likened such action to ‘burying our heads in the sand.’ While Nixon was directly involved, Moon noted that there was no evidence he personally committed any atrocities. Such actions might be repugnant to people now, but this was ‘how things were done’ at that time. Moon argued that the Nixon memorial would serve to spark curiosity about why it was erected in the first place.

Auckland mayor Phil Goff convened a council team to consider how best to address the concerns of all parties. One suggestion was to add a plaque or interpretative panel presenting the iwi view of the events at Rangiaowhia. This met with widespread approval, including from a descendant of Nixon. Tainui historian Rahui Papa ‘applauded’ the suggestion and recommended seeking advice from Māori on the wording, to ensure ‘that the other side of the story is actually told.’ Nixon’s descendant agreed that iwi should decide on their account of events for the memorial.

If the monument was removed, Nixon’s descendant was adamant that his ancestor's remains should stay where they were – a view that was shared by Te Pou. A small poll conducted by the Manukau Courier found little support for removing the memorial, with only 11% of those who responded believing it should go. For 52%, ‘it was part of our history and should stay’. A number of those who supported leaving the memorial where it is thought that ‘both sides of the story should be told’.

At the time of writing the Nixon memorial remains in place and no additional plaque has been added.

Thinking critically about historic monuments

Ewan Morris suggests applying the ‘language of basic arithmetic’: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division, when thinking about monuments like the Nixon memorial.

Interrogating historic memorials and markers – Skills | Te Akomanga

Captain John Hamilton statue

Another monument to a colonial figure deemed worthy of removal in The Spinoff article was that of Captain John Hamilton, described by Vincent O’Malley as a ‘relatively minor historical figure’. Like Marmaduke Nixon, Hamilton died from wounds received in battle, in his case at Pukehinahina, Gate Pā, in April 1864. In 2018, Waikato kaumatua Taitimu Maipi took a claw hammer and red paint to the statue of Hamilton located in Civic Square in the city named in his honour. Maipi described Hamilton as a ‘murderous asshole’ and called for the city to rid itself of its colonial title and be renamed Kirikiriroa, its original Māori name. He also argued that Bryce, Grey and Von Tempsky streets should also go, as they honoured men who had waged war on iwi (more on this debate later).

Correcting colonial history

Te Pāti Māori co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer (Ngāti Ruanui, Ngā Ruahine, Ngā Rauru) argued that the removal of such statues and street names was not about ‘wiping out New Zealand's colonial history but correcting it. It’s actually about agreeing that we can’t be blind to racism’. Their removal didn’t mean they would be forgotten, but by giving them prominence on ‘the main street, you’re glorifying them.’Gift to the city

Hamilton never set foot in the town which was founded after his death. This is not unusual. Many towns and cities in Aotearoa New Zealand are named after imperial figures who never visited the country, let alone the settlement named in their honour, but what is particularly interesting (or perhaps perplexing) about the Hamilton statue is that it is not a relic from the nineteenth century. It was gifted to the city in 2013 by a prominent Waikato businessman, Sir William Gallagher of the Gallagher Group, ‘to celebrate 75 years in business’.

Questions as to the sentiment behind Gallagher’s gifting of the statue erupted following a speech he gave to business leaders in Hamilton in 2017. In it he declared that the ‘Treaty of Waitangi papers on display at the National Library were fraudulent documents’ and went as far as to describe the Treaty itself as ‘a rort.’ He asserted that Māori ‘gave up sovereignty’ and ‘now we have these bloody reparations going on.’ Some walked out in protest, with one local businessman describing Gallagher’s comments as ‘disheartening’. Taitimu Maipi marched into the Gallagher Group Limited office in Hamilton dressed in a white supremacist costume with KKK on it and declared, ‘enough is enough … there are some racist people [here] that are just as bad as those ones over in America’. Waikato-Tainui chair Parekawhia McLean described Gallagher’s remarks as ‘outdated, privileged and sad’. Facing a considerable backlash, Gallagher issued an apology ‘for any offence taken and in particular for any inference that my views somehow represented an anti-Māori sentiment.’ Noting that he was a businessman, not a historian, he acknowledged that he needed ‘to seek more research and understanding on this topic from various viewpoints.’

In 2019 Waikato-Tainui formally asked for the removal of the Hamilton statue, arguing that glorifying colonial-era figures in statue form was a reminder of the devastating effects of British injustice. In mid-2020 the statue remained in place. In the build-up to a planned Black Lives Matter protest in the city in early June 2020, Taitimu Maipi made known his intention to remove it. Hamilton mayor Paula Southgate accepted that many people found it ‘personally and culturally offensive.’ Hamilton, she believed, could not ignore what was ‘happening all over the world and nor should we. At a time when we are trying to build tolerance and understanding between cultures and in the community, I don’t think the statue helps us to bridge those gaps.’ Concerned also at the prospect of wilful damage to public property, the council consulted with Waikato-Tainui, the Gallaghers and other councillors and then removed the statue on 12 June before the planned protest march.

John Bryce – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

George Grey – Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

Gustavus Ferdinand von Tempsky - Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

Gate Pā | War in Tauranga – NZHistory

Sir William Gallagher's 'outdated, privileged and sad' view of history – Stuff

Opposition to removing statue

Not everyone agreed with this decision. Mayor Southgate observed that she had witnessed the ‘worst arguments put on both sides of the debate’ and had received personal abuse on the matter. Deputy mayor Geoff Taylor suggested prosecuting those threatening to tear the statue down, an action Southgate compared to ‘throwing oil at the fire.’ Taylor expressed concern that the decision to remove the statue was ‘some woke response to the outrage in the US’. While conceding that there was an awful lot ‘we shouldn't be proud of in our colonial past’, there were things he was proud of about his European forebears, who ‘came here with nothing.’ He was not prepared to wipe this heritage away ‘because of some crazy US cop.’

History of controversy

A University of Otago study released in June 2020 stressed that controversy over public statues is nothing new. This research examined 123 statues of named individuals identified on outdoor public land in New Zealand and found almost a quarter had been attacked at least once. Six of the statues had been decapitated a total of 11 times. The Otago research confirmed that the statue subjects were overwhelmingly Pākehā men (87%). Only 6% of the statues were of Māori, who now comprised 15% of the population. One per cent each commemorated people of Asian or Pacific ethnicity, despite these groups making up 12% and 7% of the population respectively.As with the Nixon memorial, it was suggested that the Hamilton memorial be relocated to a museum. Mayor Southgate thought there was no point putting the statue back up on its original site, as it would undoubtedly be vandalised. In her eyes, Civic Square ‘had to be a place where all people feel welcomed, and nobody feels offended.’ The museum was ‘not a bad solution,’ as it was a place where the ‘proper story could be told, where there’s a balanced history.’ Southgate acknowledged that the city needed to have an ‘urgent and brave’ discussion about its colonial past. Mayor Southgate indicated that the statue would be stored in a ‘secret council facility’ while there were urgent discussions with councillors and the wider public about what they would like to see happen to it long-term.

The National MP for Pakuranga, Simeon Brown, labelled the Hamilton City Council as ‘incredibly weak’ for giving in to the demands of ‘vandals’. Brown used Twitter to ask, ‘once we have finished tearing down statues should we start burning books?’ This action, he believed, set a ‘dangerous precedent’ for other councils. Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters chimed in, asking why ‘some woke New Zealanders’ felt the need to ‘mimic mindless actions imported from overseas?’ A self-confident country, he argued, ‘would never succumb to obliterating symbols of their history, whether it be good or bad or simply gone out of fashion.’

Hamilton mayor suffers from abuse after Captain Hamilton statue removal – RNZ

Shane Te Pou | Statues belong in Te Papa, not in our public places – Stuff

Hamilton City Council 'weak' for pulling down colonial statue – Stuff

Part three: Hamilton continues to grapple with its colonial past

Proposals for the renaming of Hamilton as Kirikiriroa and for Von Tempsky, Bryce and Grey streets to also be renamed were addressed in a report commissioned by the Hamilton City Council in 2019. Vincent O’Malley’s research was intended to help the mayor and councillors consider such matters. O’Malley’s report summarised relevant historical information but made no recommendations on Hamilton street names or other issues. O'Malley, identified three street names as being ‘particularly egregious to Māori’, namely Grey, Bruce and Von Tempsky.

Who decides place names?

New Zealand Geographic Board Ngā Pou Taunaha o Aotearoa is New Zealand’s national place-naming authority. It is responsible for official place names, maintains the New Zealand Gazetteer, and provides advice on place names that are part of cultural redress in Treaty of Waitangi settlements. Public consultation is part of their decision process. Students interested in finding out how to make a place name proposal or have their say on a proposal can go here for guidance.Despite his previous admission that he was ‘not a historian,’ Sir William Gallagher described O’Malley’s report as ‘biased’ and ‘fake history’. Gallagher maintained that Māori weren’t the original inhabitants of New Zealand, claiming that ‘several civilisations’ had lived here before them. This view has long been expressed by some of those who can be described as ‘Treaty deniers’. Such beliefs do not stack up in the face of a broad range of evidence that New Zealand’s first permanent settlements were established between 1250 and 1300 AD by people from East Polynesia. This evidence includes radiocarbon dating, analysis of pollen (which measures vegetation change) and volcanic ash, DNA evidence, genealogical dating and studies of animal extinction and decline. Historian Scott Hamilton, writing for The Spinoff, has described Treaty of Waitangi denialism as having ‘a long, dark and absurd history.’

Gallagher’s views were dismissed by a number of scholars as ‘wacky’ and ‘racist nonsense’. O’Malley described them as ‘an attempt to delegitimise Māori as tangata whenua of New Zealand’. Matthew Tukaki, executive director of the New Zealand Māori Council, called claims that Māori were not the country’s first inhabitants ‘racist nonsense’, and argued that the ‘retelling of history in a distorted way confuses people … and emboldens the racists.’

Historical report released – Hamilton City Council

Scott Hamilton | Treaty of Waitangi denialism: a long, dark and absurd history – The Spinoff

About the New Zealand Geographic Board – Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand

Changing street names

Richard Wolfe, writing in New Zealand Geographic magazine in 1996, highlighted how travellers in some parts of New Zealand could be excused for thinking they had taken a wrong turn somewhere, with so many of the names of our streets ‘pointing somewhere else,’ namely to the British Empire. ‘New Zealand couldn’t avoid this influence, and our unswerving allegiance inspired many of the names now imposed on the landscape. Individuals – and their deeds of valour which secured this once mighty Empire – may have been forgotten, but their names endure, immortalised and enamellised on street signs.’

The apparent ‘deeds of valour’ associated with prominent figures associated with the New Zealand Wars have become a particular focus for change. In March 2021, a petition with around 1600 signatures called for the renaming of four streets – Bryce St in the central city, and Hamilton East’s Grey St, Von Tempsky St and Cameron Rd. The petition argued that ‘all New Zealanders residing in Kirikiriroa/Hamilton City are affected by the problem of living on streets named after individuals who have committed violent crimes of theft and murder’.

In April 2022, a Hamilton City Council community committee voted in favour of changing Von Tempsky St to Puutikitiki St, and nearby Dawson Park was renamed Te Wehenga Park. Bryce St and the name Hamilton itself were left untouched – for now. Tukoroirangi Morgan of Waikato-Tainui described the Prussian soldier of fortune Gustavus von Tempsky as a ‘reminder of a past filled with despair and anguish and injustice. We did not want to have a name on our street which commemorates that man’s hand in the invasion of Waikato.’ Naming a street in his honour was akin to ‘celebrating murder.’ Dawson Park was named after Captain Thomas Dawson, another figure involved in the invasion of Waikato, who eventually settled in Hamilton and served on the Hamilton Borough Council before becoming mayor.

Wiremu Puke (Ngāti Wairere) did not believe these changes were about ‘punishing early settlers’ but more a case of ‘giving people an understanding of what was on the ground originally.’ Puutikitiki references the name of the gully behind Hamilton East School that Ngāti Parekirangi, a subtribe of Ngāti Wairere, occupied prior to 1864. Te Wehenga Park. acknowledges the historic Ngāti Parekirangi – Ngāti Hānui urupā (burial ground) that was destroyed when a road cutting went through.

A ceremony was held in November 2022 to mark the changes. Local pharmacist Ian McMichael, who had applied for the name change, wanted more recognition of the history of tangata whenua in Hamilton. His own ancestor had fought alongside von Tempsky in his final battle in Taranaki in 1868.

Committee chairperson Mark Bunting said the case for change was supported by mana whenua along with the Hamilton East School, residents, and businesses. Some councillors disagreed. Deputy mayor Geoff Taylor acknowledged that ‘you’d be stupid to dispute that Von Tempsky caused Māori hurt’, but as with the earlier decision to remove the statue of Hamilton, he did not support ‘extinguishing the signs of our history.’ Fellow councillor Ewan Wilson was of a similar opinion, arguing that informative signs about the atrocities of von Tempsky would be more appropriate. He also acknowledged that ‘what happened in those times, were unforgivable by today’s standards’ – but these events occurred, and historical injustices could not be resolved by ‘ripping out or cancelling monuments and street signs.’

It is worth revisiting some of what was discussed in Part One in considering the appropriateness of judging past behaviour by contemporary moral standards. Andrew Roberts argued that while it is ‘completely illogical, ahistorical and unfair to natural justice to judge the people of the past by today’s morals, it is also very hard not to.’ Charlotte Riley, from the University of Southampton, said that while ‘a historian’s primary aim is rarely to make a moral balance sheet of the past’, she was ‘wary of the idea that people from the past should escape our moral judgement. Historians can never approach the past as neutral observers.’

Vincent O'Malley acknowledges that many monuments around the country ‘reflect the era in which they were built and it's high time for a clean-up. They're problematic in many respects so I think it's healthy to have a dialogue and conversation around this difficult history and how we want to move forward.’ O'Malley believes ‘there are a range of options for addressing the issue, but iwi and hapū must be at the forefront of the conversation’. A key step is how to ‘contextualise monuments by providing information panels from today's perspective. History is never fixed, it's a constant process of our understandings which evolve and change over time ... these monuments are a reflection of another time really.’

Ian McMichael believes that, given time, future name changes ‘won't be so controversial as maybe this name change was.’ He did not believe people would ‘forget about [von Tempsky] because of the change.’ Mark Bunting agreed. Immortalising the likes of von Tempsky in this way was no longer necessary, ‘now we had documentaries and online resources to remember their impact.’ The names of Grey St and Cameron Rd are unchanged at the time of writing.

The nearby Waipā District Council has been grappling with similar issues. In 2021 the council sought public feedback on its naming policy for streets and public reserves. One submitter, Dan Armstrong, told the council it needed to immediately remove names like Bryce St and Grey St from Kihikihi. Governor Grey was one of the key figures in the invasion of Waikato, and there was ‘no excuse in 2021 to memorialise’ someone who shaped New Zealand for the worse. He described John Bryce, the minister for native affairs from 1879 to 1884, who led the attack on Parihaka, as ‘a fundamentally awful person,’ yet ‘we and other communities around the country name streets after him, to honour him.’

Richard Wolfe | On the streets where we live – New Zealand Geographic

Hundreds sign petition to rename Hamilton streets named after 'assholes' who fought Māori – Newshub

Street name in Hamilton changed from Von Tempsky to Putikitiki – Stuff

Pride of place: Hamilton's colonial past makes way for names honouring Māori heritage – RNZ

Von Tempsky killed at Te Ngutu-o-te-manu – NZHistory

Steve Watters, Senior Educator–Historian

Community contributions