On 2 November 1868, New Zealand discarded its numerous local times in favour of a standard time nationwide. In a decision which was a triumph for convenience and economic rationality over tradition and local identity, the colony became the first country to regulate its time in relation to Greenwich mean time (GMT).

This was the first step towards an international order of time. It was also a symbolic moment of unity for a colony less than three decades old and divided by internal conflicts, not least the wars currently raging on both coasts of the North Island.

What's the time?

Sundial (Te Ara)

Before the development of broadcast media, establishing the time required a bit of legwork. In the mid-1860s you could ask a neighbour with a reliable clock, listen for the town bells or a cannon, wait for the time ball to drop, or make a trek to view the nearest public clock. If it was daytime and sunny, you could read the apparent local solar time on a sundial. By applying the ‘equation of time’ to adjust for the Earth’s axial tilt and orbital eccentricity, you had the local mean time (local solar time averaged out over a year of 24-hour days).

Local watch and clockmakers supplied timekeeping services, and some displayed the local mean time on a clock at their premises. Three were particularly noteworthy: Joseph McGregor in Wellington, Alfred Bartlett in Auckland and Arthur Beverly in Dunedin. A respected clock and watchmaker, mathematician, optician, astronomer and photographer, Beverly led the campaign for a common time, first for Dunedin and later for the whole colony.

Each city and town organised daily life according to its own clock time. But in the last week of January 1868, the status quo was upset. People using the post office or sending telegrams from their local telegraph office found that the clocks in these buildings showed a different time — Wellington mean time, or ‘telegraph time’ as it was commonly known.

Who decided, and why?

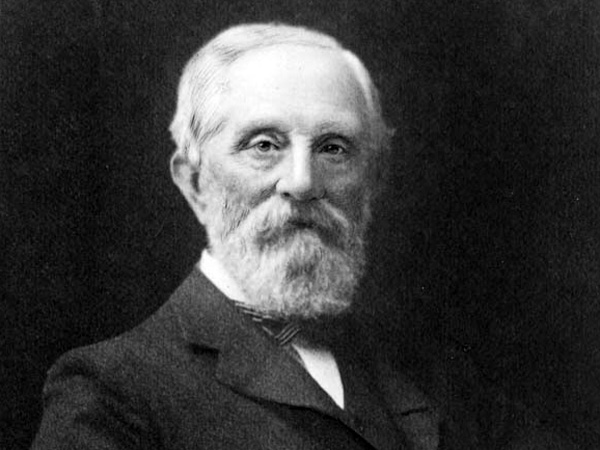

John Hall, c1880. (ATL, PAColl-3768-4-02)

The Postmaster-General, John Hall, had become aware of growing frustration among his staff and the general public that the country’s hundreds of post and telegraph offices opened and closed according to local mean time. With a time difference of 34 minutes between Invercargill and Napier, many an urgent message was not received until the following day. Invercargill’s postmaster had recognised this problem and adopted Wellington mean time in September 1867.

Hall could not force the self-governing provincial councils to adopt Wellington time, but he held sway over post and telegraph offices. In January 1868 he instructed all telegraph offices to open and close according to Wellington mean time. Post offices, many of which shared the same building, were to do likewise.

Making it possible

New Zealand's telegraph network in 1868 (Te Ara)

Hall’s edict was only practicable because of the extensive groundwork that had been laid since 1862, when the first telegraph lines had been erected between Christchurch and Lyttelton, and Dunedin and Port Chalmers. By January 1868, about 74% of the 220,000 non-Māori New Zealanders had access to the telegraph.

In 1863, the Wellington provincial government established the country’s first ‘official’ observatory — the Provincial Observatory — which provided the first publicly funded timekeeping service.

Battle of the clocks

- Auckland (correct)

- New Plymouth (fast three)

- Picton (fast three)

- Nelson (fast six)

- Christichurch (fast eight)

- Hokitika (fast 15)

- Dunedin (fast 17)

- Invercargill (fast 25)

- Napier (slow nine)

- Wellington (correct).

Parliament began sitting in Wellington in 1865. The General Government had recognised the need for a more central location than Auckland, its previous base. In 1864, 62% of New Zealand’s non-Māori, non-military population lived in the South Island, principally because of the Otago gold rushes and the unsettled state of much of the North Island.

In 1866, the need for a solution to the problem of ‘local time’ became more urgent with the successful laying of a submarine telegraph cable across Cook Strait. The South Island’s telegraph network was now linked to Wellington. However, much of the North Island, including all of Auckland Province, remained cut off from the rest of the colony, in large part because Māori opposed to the expansion of Pākehā settlement controlled the central North Island.

Hall anticipated some disagreement from provincial leaders. One of the first newspapers to comment was Nelson’s Colonist, which on 24 January supported Hall’s decision. ‘The necessity has arisen for having one time for the whole of New Zealand, the same as in Great Britain, where Greenwich time regulates the clocks and watches of the entire country.’ [1] It was mistakenly believed in New Zealand that Britain had universally adopted GMT. In fact, GMT was not legally enforced on the island of Great Britain until 2 August 1880.

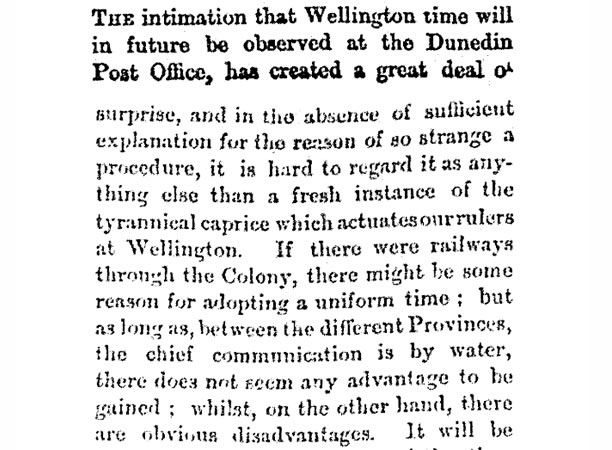

Public debate in Otago

Extract from article in the Otago Daily Times, 12 March 1868. (PapersPast)

While most provinces accepted the new clock time, Otago, then the most populous, richest and proudest, saw it as an attack on its autonomy and identity. In March 1868 there was intense debate in its newspapers. In the Otago Daily Times on 12 March, it was argued that ‘in the absence of sufficient explanation’ the decision seemed to be ‘a fresh instance of the tyrannical caprice which actuates our rulers at Wellington’. [2] To make matters worse, Dunedinites had been told to adjust their clocks by 20 minutes, not the correct 17 minutes.

A letter by ‘Meridian’ (probably James Hector) published in the ODT on 23 March — the day the term ‘battle of the clocks’ was first used — cautioned the local authorities against making a hasty and possibly ill-formed decision. ‘Before the meridian of any place is selected as the regulator for the whole Colony, it should be inquired into how such place is situated with respect to the chief towns of the Colony, so that as little difference as possible may be made in the real time of these centres of population.’ [3] Basing a standard time on the Christchurch meridian, which was said to bisect the country, would result in much less inconvenience in the principal towns of the colony than the adoption of Wellington time. Dunedin took this advice and continued to use two times.

On 27 May 1868, the Otago Provincial Council debated a motion and an amendment on the matter without reaching agreement. The last man to speak, William Hunter Reynolds, the council’s Speaker and Member of Parliament for Dunedin City, expressed the hope that the motions would be withdrawn. Acknowledging the depth of feeling in Dunedin on the matter, he promised to have the issue debated in the General Assembly. The motion and the amendment to it were withdrawn.

The general government debate

On 2 September 1868, Reynolds kept his promise, instigating a debate in the House of Representatives during the third session of the fourth Parliament. He argued that Christchurch time should be observed, as the city ‘was nearly the centre’ of New Zealand. This ‘would equalize the time … throughout the Colony.' Reynolds moved ‘that Christchurch mean time be observed throughout the Colony, and that the Government introduce a Bill legalizing the same’, before traversing the issue in some detail.

Only three other speakers rose to the occasion. Major Charles Heaphy VC, the MP for Parnell, took the traditionalist position that ‘Wellington, Christchurch, or any other place should have no other time but their own.’

John Hall then explained his reasons for enforcing Wellington time on his post and telegraph offices, adding that ‘in a good many parts of the Colony the inhabitants, knowing that this time was kept with great punctuality at those offices, regulated their own clocks by those at the telegraph stations and the post offices.’

Hall proposed an amendment to Reynolds’ motion: that ‘“Christchurch” be struck out for the purpose of inserting “New Zealand.”’ He wanted to seize back the initiative from Reynolds by making the motion a government measure. He was also anxious, as the representative of a Canterbury electorate (Heathcote), to avoid any hint of parochialism that might antagonise southern and North Island members. Reynolds had no objection to this amendment.

The fourth speaker, MP for Clutha James Macandrew, ‘did not see any necessity for debating the propriety or otherwise of adopting one uniform time throughout the Colony’. Reynolds’ ‘Motion, as amended, [was] agreed to.’ [4]

Dr Hector sets the time

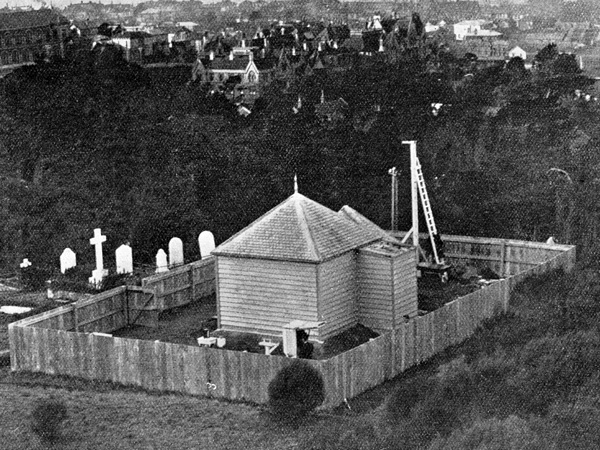

Colonial Time Service Observatory, Wellington (ATL, 1/2-044047-F)

Government scientist Dr James Hector was tasked with resolving the matter. His advice was that while ‘the absolute longitude of any place in the colony has not yet been determined’, it would be best to adopt the meridian of 172˚30΄ E for New Zealand mean time; this ‘would cause the least inconvenience’. This meridian runs just west of Christchurch, Cape Farewell and Cape Maria van Diemen.

The Government approved Hector’s recommendation and laid it before the House of Representatives. On 31 October 1868, it was announced in the New Zealand Gazette that New Zealand’s clock time would be 11 hours 30 minutes ahead of GMT.

At noon on Monday 2 November 1868, all well-regulated clocks in the North and South Island that were either connected by the telegraph to Wellington, or regulated by a telegraph office clock, struck 12 at the same moment Wellington’s town clock did. Although this was not recognised at the time, this was a significant moment of union for a fledgling and divided colony.

Hector’s reasoning stood the test of transnational debate in 1884, when world leaders assembled in Washington DC for the International Meridian Conference voted overwhelmingly to accept Greenwich as the Earth’s prime meridian. The conference in effect endorsed Hector’s decision without being aware of it.

On 1 January 1946, New Zealand formally adopted a standard time set 12 hours ahead of GMT, or 180° east of Greenwich. This meridian lies well to the east of New Zealand’s main islands, about two-thirds of the way from Banks Peninsula to the Chathams. Its adoption simplified the relationship between NZST and GMT. However, it means that dawn arrives very late in midwinter, especially in south-western parts of the country. Around 1 July, the sun rises above the horizon in Invercargill after 8.30 a.m. but still sets after 5 p.m. Today GMT is known as UTC (Universal Time Coordinated or Coordinated Universal Time).

Notes

[1] 'Telegraphic Time', The Colonist, 24 January 1868

[2] 'Inveniam viam aut faciam', The Otago Daily Times, 12 March 1868

[3] 'To the Editor of the Otago Daily Times', The Otago Daily Times, 23 March 1868

[4] All quotes in this section are from 'Christchurch Mean Time', New Zealand Parliamentary Debates, vol. 3 (1868): 106-108

Further information

This web feature was written by Gerard S. Morris and produced for the web by David Green and the NZHistory team.

Links

- The Vogel era (NZHistory)

- Timekeeping (Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

- World Time & Convertors (GreenwichMeanTime.com)

- John Hall biography (DNZB)

- James Hector biography (DNZB)

- Arthur Beverly biography (DNZB)

- Charles Heaphy biography (DNZB)

- James Macandrew biography (DNZB)

Books and articles

- George Eiby, 'The New Zealand government time service: an informal history', Southern Stars, no. 27 (1977)

- Gerard S. Morris, 'Time and the making of New Zealand: a theme on the development of a settler society 1840 to 1868', MA thesis, University of Canterbury, 2012

- Eric Pawson, 'Local time and standard time in New Zealand', Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 18, no. 3 (1992)

- A.C. Wilson, Wire & wireless: a history of telecommunications in New Zealand 1860-1987, Dunmore Press, Palmerston North, 1994

Community contributions