The images that frame these learning activities are intended to get students thinking about concepts related to mana, resistance, colonisation, decision-making and historical notions of change and continuity.

They are by no means exhaustive and do not illustrate, for example, the multiple artistic, musical and literary responses to colonisation that enrich Aotearoa New Zealand’s culture and heritage.

The book Protest tautohetohe: objects of resistance, persistence and defiance is a good resource to support this mahi and to uncover more history associated with the kaupapa and history of resistance, persistence and defiance.

Learning intention

Whether you use all these images just one image, or other images, it is hoped that the following activities will support students to understand that:

- Māori have responded in various ways to colonisation and breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi over time

- Recent protest movements and forms of resistance sit within a long tradition of groups and individuals who have worked to secure and maintain mana motuhake.

Key concepts

- mana motuhake

- tino rangatiratanga

- colonisation

- resistance

- action

- change and continuity

- trends

Aotearoa New Zealand's histories curriculum (Years 9–10)

Understand

- Colonisation and settlement have been central to Aotearoa New Zealand's histories for the past 200 years

- The course of Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories has been shaped by the use of power

Know

Tino Rangatiratanga me te kāwanatanga | Government and organisation

- Sovereignty vs rangatiratanga: wars, laws and policies

The Crown asserted its power to establish a colonial state that in consequence diminished mana Māori. Over time, Māori have worked inside, outside, and alongside the Crown to renegotiate the colonial relationship with the Crown and to affirm tino rangatiratanga.

Do

- Identifying and exploring historical narratives

I can construct a narrative of cause and effect that shows relationships between events. By comparing examples over time, I can identify continuity or changes in the relationships. I can recognise that others might interpret these relationships differently.

Definitions/Concept maps

To support this learning it is helpful to clarify key terms by providing definitions and/or getting students to complete concept maps.

- Mana motuhake: self-determination, independence, sovereignty, authority – mana through self-determination and control over one’s own destiny.

- Colonisation: a practice of domination, which involves the subjugation of one people by another.

Concept maps enable students to explore a concept by getting them to think about things like:

- defining the concept

- thinking about what it leads to

- what it looks like

- seeing whether they can come up with historical/contemporary/personal examples of the concept.

Resistance/Mana/Colonisation/Change/Continuity would be good concepts for students to ‘map’ in preparation for the image activity.

Image activity

- Photocopy the images below and enlarge to A3 size.

- Make enough sets so students can work in groups with a set each. You could also laminate a set and pin these to the classroom wall.

- Working in groups, students discuss what they see in the images. Visual Thinking Strategies suggest three simple questions that can be used to explore images:

- What’s going on in this picture?

- What makes you say that?

- What else can we find?

- From this examination, can any of the groups/events be identified?

- Organise the images in chronological order. This will most likely involve guesswork based on what students see in each image.

- Groups brainstorm conclusions about Māori resistance to colonisation? Share ideas.

- Teacher presents the images on a slide show in the order as set out below and including the information about each image. Go through these slides once the students have attempted the tasks above. Discuss and keep a note of any questions.

This activity will generate research questions for students. Each group/student, for instance, could find out more about the history related to an image that interests them. For younger students, this research could begin by finding out the when, what, who and why related to the history of the group/event.

For senior history students, the following could also be attempted:

- Using the Taxonomy of Action sheet, reorder the images and group them according to type of action.

- Write down two or three conclusions that can be drawn about Māori resistance to colonisation. (Consider continuities, trends over time, forces.)

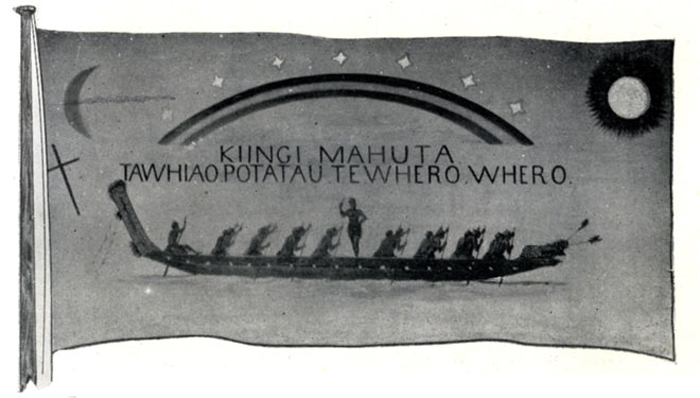

1858—present day: The Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) was founded in 1858 with the aim of uniting Māori under a single sovereign. Waikato is the seat of the Kīngitanga. Seen on the flag is the name Kiingi Mahuta Tawhiao Potatau Te Whero Whero – the full name of the third Māori king, Mahuta.

1862: Te Ua Haumēne founded the religion known as Pai Mārire. The rituals of Pai Mārire (good and peaceful) focused on niu (news) poles, constructed from ships’ masts. The cracking of the ropes, along with the flags, were believed to convey messages from God on the wind. Pai Mārire influenced Tāwhiao, the second Māori King, as well as Tītokowaru and Te Kooti.

Mid-1860s—present day: Tūhoe did not sign Te Tiriti and over generations have continuously demanded mana motuhake (self-determination/autonomy). Repeated and brutal invasions of the Urewera district from the late–1860s partly reflected its status as a place of sanctuary for Māori from elsewhere who were seeking to elude government forces.

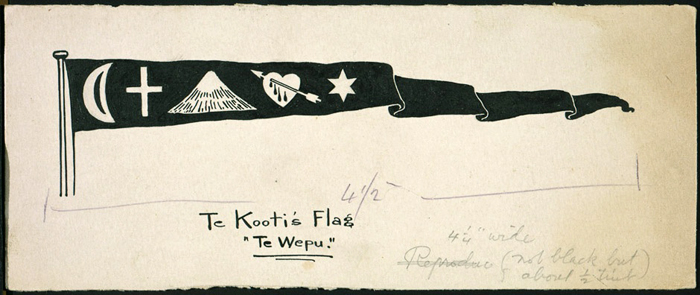

1868—1883: Te Kooti was a Māori leader and founder of the Ringatū religious movement. He was exiled to Rēkohu/Wharekauri (the Chatham Islands) in 1866 but escaped two years later and successfully evaded government authorities in the central North Island and East Coast regions. He was eventually pardoned in 1883.

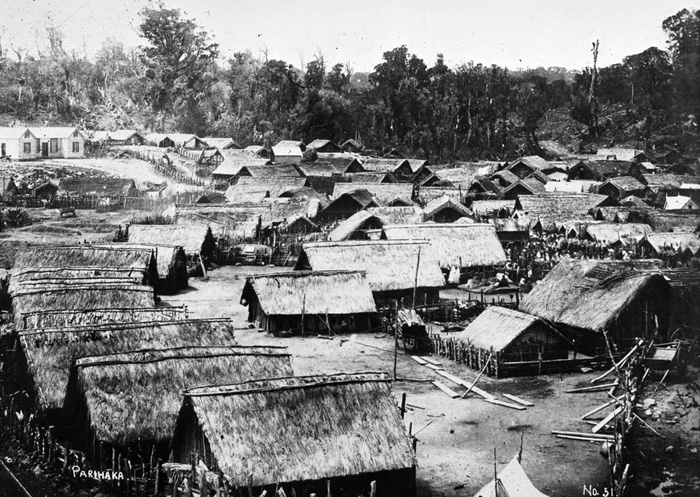

1860s—present day: Parihaka is a living community that was established by Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi in the 1860s. It became a centre of peaceful resistance and a rallying point for many Māori. The village was ruthlessly invaded in 1881, known as Te Rā o te Pāhua (the day of plunder). Men were arrested without trial and taken to Te Wai Pounamu. Those who remained experienced a terrifying period of looting, ransacking and rape.

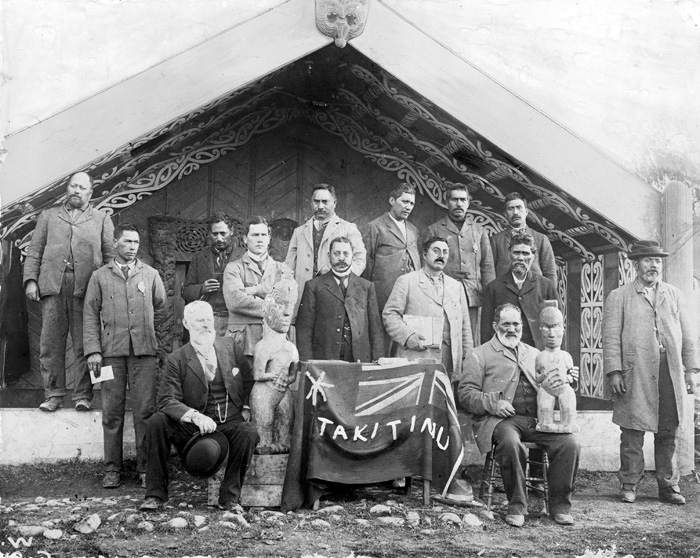

1900: The Māori Councils Act set up councils in Māori districts all over the country. They acted as local authorities and reported to the government on issue of concern to Māori. This image shows the Takitimu Council (Gisborne) set up in 1902.

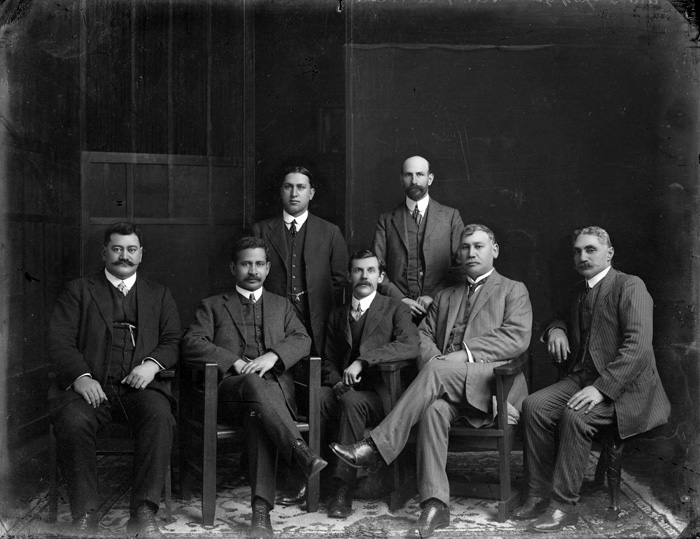

1909: The Young Māori Party: this group of Māori men were interested in improving Māori health and welfare. The members of Parliament who have been identified in this photograph are (front from left) Māui Pōmare, Apirana Ngata, and (fourth in row) James Carroll. They played important roles in the Young Māori Party, an early 20th-century Māori organisation which sought to improve the well-being of Māori through parliamentary politics.

1918—present day: Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana founded a Māori religious movement which, in the late 1920s, also became a major political movement. He challenged the government and the British Crown to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi. In January each year politicians still travel to Ratāna, near Whanganui, to engage with Māori.

1951—present day: The Māori Women’s Welfare League was set up as a national organisation to promote the health, education and general well-being of women and children. It received support from the government.

1970: Members of the activist group Ngā Tamatoa sit on Parliament’s steps in late 1972. Ngā Tamatoa played an important role alongside other organisations in revitalising the Māori language, and represented a growing number of young urban Māori involved in protest movements. Some members of Ngā Tamatoa also pushed for greater representation of Māori in the union movement.

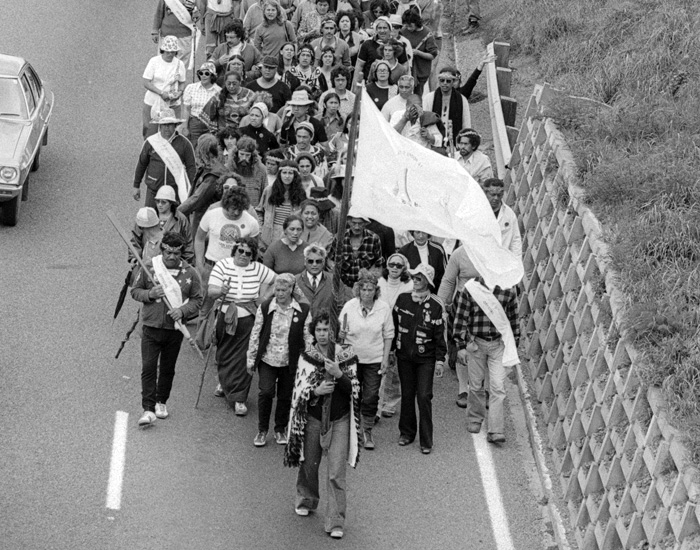

1975: In the early 1970s, growing Māori anger over land alienation led to activism. Te Rōpū Matakite o Aotearoa (those with foresight) was led by Whina Cooper. This famous hīkoi travelled the length of Te Ika-a-Māui, visiting many marae and raising awareness about Māori land alienation.

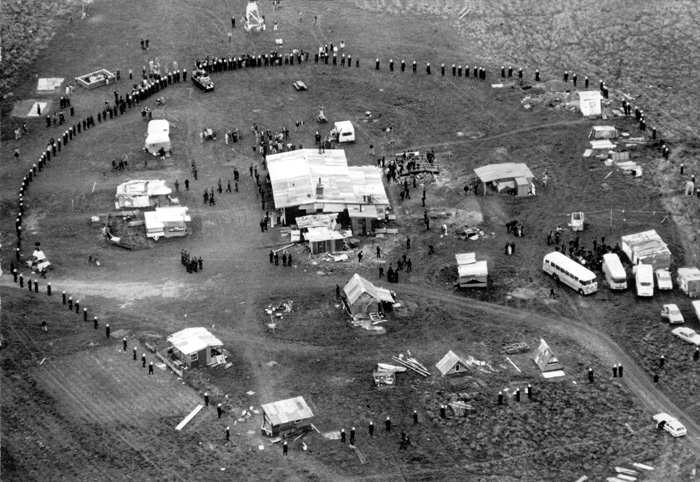

1977: In 1976 the government proposed selling part of Auckland’s Bastion Point reserve for luxury housing. Led by Joe Hawke, the Ōrākei Māori Action Committee occupied Takaparawhā (Bastion Point reserve) in January 1977. The occupation lasted for 506 days. It ended on 25 May 1978, when the government sent in police to remove the protesters and demolish their makeshift homes. The new housing was never built, and much of the land was returned to Ngāti Whātua under a Treaty of Waitangi settlement.

1980–2005: Founded by Matiu Rata, who split from the Labour Party, this movement and political party promoted ‘mana Māori motuhake’. The fundamental purpose of the party was to retain and regain Māori land. At the 1981 general election Mana Motuhake won over 15% of the Māori vote. Mana Motuhake members Sandra Lee, Alamein Kopu and Willie Jackson later entered Parliament as list MPs representing the leftist Alliance grouping.

1995: The 79-day occupation of Moutoa Gardens was intended to restore the mana of the Whanganui people over the site. Te Rūnanga Pākaitore claimed that it had been set aside from the purchase of Whanganui in the 1840s; the local authorities denied this.

2004: The foreshore and seabed hīkoi began in Northland and ended in Wellington. Its purpose was to protest against proposed legislation confirming the Crown’s ownership of New Zealand's foreshore (the land below the highest high-tide mark) and seabed.

2004: The Māori Party was formed to represent Maōri interests. It contests Māori electorates. In 2005 it won four of the six Māori electorates and from 2008 to 2017 its co-leaders served as ministers in the National-led government.

2016: In response to Fletcher Building’s planned housing development on the Oruarangi block, near Auckland airport, the protest group SOUL (Save Our Unique Landscape, led by Pania Newton and others) set up camp beside Ihumātao Quarry Road on 4 November 2016. In 2019 opposition grew, with hundreds of people occupying the area. Following intervention by King Tūheitia, the government bought the land from Fletchers’ for $30 million in 2020.

Ricky Prebble, Educator–Historian

Community contributions