Students may find learning about history emotionally difficult for a wide range of reasons. Incorporating emotional literacy in teaching can help manage that difficulty and promote students’ personal, social and emotional development.

Using this page

This page begins with a discussion about the importance of attending to students’ emotional responses when learning history, before offering suggestions and approaches about how this can be done in the classroom.

The ideas here are applicable across a wide range of year levels, junior to senior. Teachers should feel free to adapt the activities for their specific class.

Key concepts

- Difficult histories

- Emotional literacy

- Head, hand, heart

The difficulty throughout our history

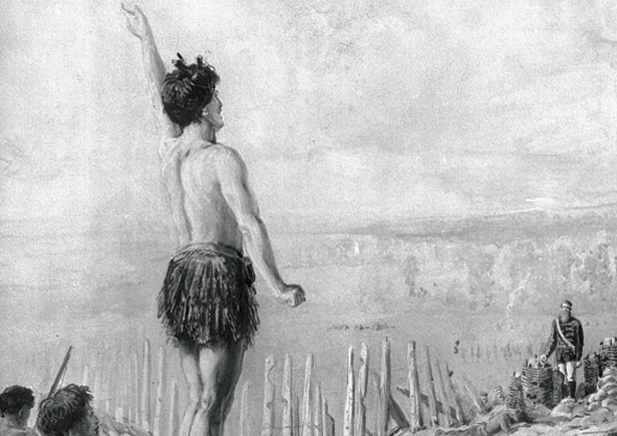

‘Difficult histories’ has emerged as a label to describe the teaching and learning of Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa, the New Zealand Wars of the nineteenth century.

I find myself grappling with this label, not because it’s inaccurate but because it feels incomplete. Yes, this history can be difficult – it feels uncomfortable, unsettling, challenging and confrontational, a thing to be avoided. But the term ‘difficult histories’ doesn’t really articulate what is difficult, let along how to respond to these difficulties.

Learning about this country’s colonial past is hard, but war is only one part of that past. And there are plenty of difficult histories beyond colonisation, such as a pacifist student learning about war and gas chambers, a Pasifika student learning about the Dawn Raids, a queer student exposed to homophobic views as they study Homosexual Law Reform.

Teaching history can be difficult, full stop.

The gap at the heart

Finding a balance

Remain alert and sensitive to the relationship between the head and the heart. At Pukeahu National War Memorial Park, one of our educational principles is to balance critical and emotional responses.

Teachers who are aware of this balance can discuss it with their students. They can deliberately design learning experiences that encourage genuine care about the people – past and present – who have experienced the trauma of war or other stressful events.

At the same time, teachers can help students remain critically engaged with the kinds of emotions they experience or encounter at sites of national significance.

My teaching used to emphasise what people thought and did, rather than what they felt. As a result, my students were denied a more holistic and accurate understanding of people’s perspectives and related actions.

I’m not the only one to notice this absence. In Head, hand, heart: the struggle for dignity and status in the 21st century, David Goodhart argues that Western nations suffer from a societal condition he describes as ‘Peak Head’, where cognitive achievements take precedence. He suggests that technical and practical abilities (hand) and social and empathetic skills (heart) have been devalued.

Head, Hand, Heart by David Goodhart review – Guardian

The educationalist Ken Robinson argued a similar point when he said that the system of public education was to produce university professors – people who typically “live in their heads… [and] look upon their body as a form of transport for their heads.”

Do schools kill creativity? | Sir Ken Robinson – YouTube

Why such focus on the head? Are feelings harder to identify than thoughts? Two whakataukī attest to the fact that both are difficult:

He aorere ka kitea, he huatau e kore e kitea.

The passing clouds can be seen, but passing thoughts cannot be seen.

Edward Shorthand, Traditions and Superstitions of the New Zealanders – Early New Zealand Books

He kokonga whare e kitea, he kokonga ngākau e kore e kitea,

A corner of a house may be seen and examined, not so the corners of the heart.

Connecting the head to the heart to the hand

Teaching colonisation (and the other examples above) is deeply emotional. There is pain and intergenerational mamae, there is shame, guilt and anxiety.

Acknowledging these emotions, identifying and examining them, allows students to understand them. From there, they can begin expressing other emotions they experience when studying history, such as curiosity, pride, and the joy that comes with feeling informed and empowered.

Before leaving the classroom in 2020 I started paying more attention to the emotional aspect of teaching, he kare-ā-roto.

The idea of linking the head, hand, and heart caught my attention as a simple articulation that mapped the hinengaro, ngākau and tinana, showing the intersection of cognitive, affective, and active spheres of learning.

Supporting emotional exploration with the Wheel of emotions

Resource: Wheel of emotions

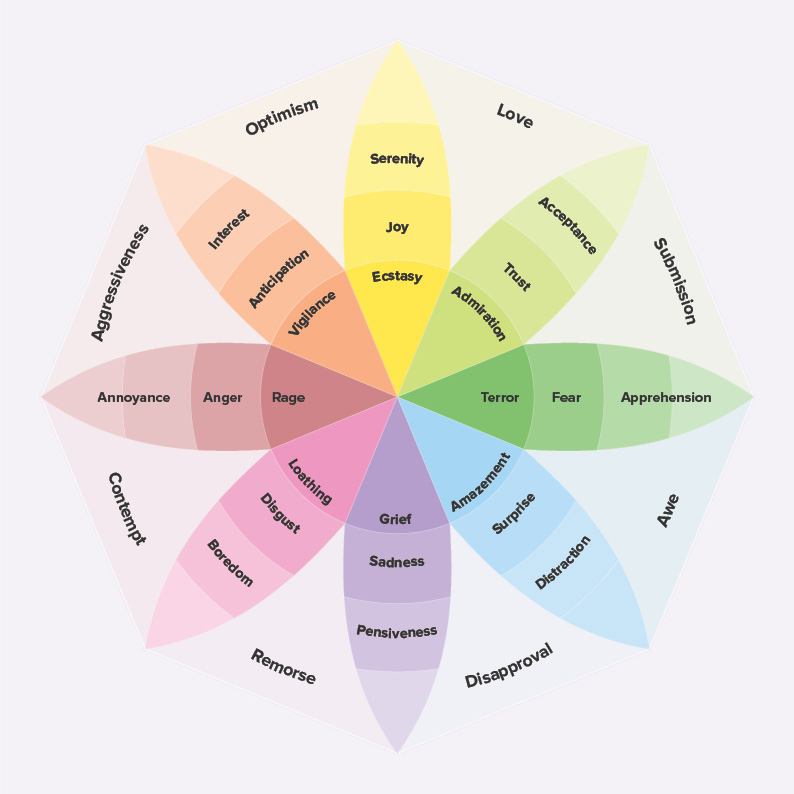

Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of emotions can support student discussions and lead to growing awareness and understanding of how emotions influence people’s views and related actions.

Wheel of emotions resource and prompting questions (PDF, 181KB)

When I was teaching Year 13 history, the analysis and articulation of emotions enabled my students to understand different narratives about Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki. A class learning about so-called ‘difficult history’ became curious and empowered.

In a multi-cultural Year 10 Social Studies class, the Wheel was effective in supporting students to communicate more detailed and nuanced explanations of people’s perspectives related to contemporary issues.

But it is difficult – I remember being strongly challenged by a Pākehā student in response to the concept of shame. I had introduced the concept badly, but in hindsight I think the student appreciated the opportunity to think about these feelings – something had ignited their interest and we continued to discuss our views for weeks.

Teaching suggestions

Prompt: Ways to teach emotions and history

The Wheel of emotions resource can get students attending to their own and others’ emotions. Use it and the following resources to get them talking about, identifying, and articulating emotions.

Directly focus on emotions with read-alouds

Trace Moroney’s Feelings series cover several emotions students will be familiar with. Use one for a new read-aloud each week.

Stories about emotions

Stories are central to children’s developing understanding of the world around them and its history.

Inside Out is a film that explores emotions as relatable characters and works well across a range of year levels.

Whakataukī

Whakataukī encapsulate traditional knowledge in a concise way, providing guidance on how to understand and manage life.

This rauemi is a taonga – it is a selection of whakataukī related to Māori emotions. Each one is paired with an image and explanation that can easily be printed out.

He Kare-ā-roto – University of Waikato (PDF, 11.6MB)

Oral history

The lived experiences of your students and their communities are valuable and deeply personal, adding specificity and emotional resonance to histories.

Find local people with experience of the topics your students are exploring and ask them to speak with your class.

Using oral history projects to boost social engagement learning – Edutopia

Primary sources

As Vincent O’Malley says, sources like letters, diaries and newspaper accounts give “a real sense of the range of emotions and feelings that people experienced.”

If studying Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa, use the first-hand accounts in O’Malley’s recent book.

Voices from the New Zealand Wars – Bridget Williams Books

Making difficult emotional terrain safer

Exploring all our difficult histories could come crashing down if healthy and safe relationships are not established. Teaching emotive and controversial history requires both teachers and students to engage in an emotional way with the subject matter.

Staying connected

Avoid the pitfall of students feeling like they’re just learning ‘dead history’ by shuttling between the past and the present.

The historical concept of change and continuity reveals the relevance and humanity of the past, helping students understand how the past influences the present – and how it can be very different.

Everyone in the classroom needs to feel comfortable about this, and able to say whether something they are learning about makes them feel angry or sad.

Emotionally secure classrooms where this can happen are good places to learn and promote students’ personal, social and emotional development. It is crucial to attend to the tikanga of the class and the wider school.

Then, this history of intolerance and resistance, pride and prejudice, legal injustice, of prophetic proclamations and earth-shattering displays of mana and loyalty, can become charged and transformational.

Whāia te iti kahurangi; ki te tūohu koe, me he maunga teitei

Seek the treasure that you value most dearly; if you bow your head, let it be to a lofty mountain.

Ricky Prebble, Educator–Historian

Community contributions