Looking at our experiences of two pandemics a century apart provides an ideal opportunity to explore a number of important historical thinking concepts that those of you familiar with Peter Seixas and Tom Morton’s Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts will recognise. These are intended to provide pathways for students to achieve a greater understanding of what has happened in the past, rather than just remembering ‘stuff’ like dates and people. If you are unfamiliar with this work, you can read more about these historical concepts here: Historical Thinking Project.

In summary, the ‘big six’ concepts are:

- historical significance

- the use of primary source evidence

- cause and consequence

- historical perspective-taking

- continuity and change

- the ethical dimension of history.

Comparing our experiences of the 1918 ‘Spanish’ flu pandemic with that of COVID-19 a century later provides a meaningful context in which to explore historical significance, perspective, and continuity and change.

We can view significant events as those that result in great change over long periods of time for large numbers of people. A person or event can acquire historical significance if we link them or it to larger trends and stories that reveal something important for us today. The significance of the 1918 flu isn’t confined to the few months that the disease ravaged the population here and the several years it raged around the world. It is not just about the number who became ill or died as a result of the pandemic.

What were the longer-term impacts on New Zealand and its people? What, if anything, did we learn from these experiences? How did the experience of 1918 shape our response to COVID-19? Were the effects of the pandemic felt equally across the country? What was the experience like for iwi and hapū, for instance? Asking students to explore the similarities and differences between the events of 1918 and 2020 can also help them to understand their own place in history. What, if any, seem to be the things that have stayed the same, and what is different about the two experiences? What explanations can they think of for why things have changed? What similarities and differences are there between the way people reacted to events in 1918 and in 2020?

Significance can also depend upon your perspective and personal circumstances. People react differently to such events on the basis of a number of factors, including the extent to which they were impacted negatively by the experience. The reactions and attitudes of parents may vary greatly from those of their children. Likewise, the experiences of people whose livelihoods have been affected severely by the circumstances surrounding a pandemic may vary from those who have been less affected. What were the perspectives of the politicians or medical experts who responded to the situation?

By looking at examples in history to identify and question change and continuity, students can be encouraged to acknowledge the vast and multiple continuities that underlie change, and which contribute to the human experience. It can be easy to misunderstand history as a list of events. Helping students to understand history as a complex mix of continuity and change allows them to gain a fundamentally different sense of the past.

Using their own experiences of living through the impact and consequences of COVID-19, students can use the activities that follow to explore these important historical thinking concepts.

The following links will help you and your students tackle these tasks:

- The 1918 influenza pandemic

- Comparing pandemics a century apart

- Epidemics

- Te hauora Māori i mua – history of Māori health

- Unite against COVID-19; the page on health data is especially useful

A. Comparing pandemics a century apart

— Refer to the Classroom Conversation, Comparing pandemics a century apart, and your own knowledge, to help you with these activities:

- Draw up a chart with two columns.

- In one column list, what you see as being some of the main differences between what happened in 1918 and 2020.

- In the other column list what you see as being some of the main similarities between what happened in 1918 compared with 2020.

— Dr Warwick Brunton is a health historian and former public health administrator. In April 2020 he wrote an imaginary letter from the perspective of Dr Joseph Frengley, acting head of the Department of Public Health, Hospitals and Charitable Institutions in 1918, to Dr Ashley Bloomfield, the Director-General of Health in 2020. You might find it interesting to read his letter here.

— Imagine you could write a letter to someone your own age, alive at the time of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Describe to them what life has been like for you during the time of COVID-19.

- Explain to them the alert system introduced to battle the pandemic and what life has been like in levels 3 and 4, in particular.

- Describe some of the things you have found the easiest and the hardest to cope with during these alert levels.

- Write about some of your feelings at this time, or some of the things that have been happening at home and in your community.

B. Eyewitness to history a COVID-19 time capsule

People have reacted differently to, and have had varied experiences of, the period of lockdown and restricted movement and activity in response to COVID-19. We have all been eyewitnesses to this history. In years to come, people studying this event will rely on our accounts to better understand what happened.

One way of recording your experiences of living in the time of COVID-19 is via a time capsule. This is a container storing a selection of objects chosen as being typical of the present time that is buried for discovery in the future. It could be something intended to be discovered at some point in the future by a stranger, a descendant or even your future self. Imagine that your COVID-19 bubble has decided to prepare a time capsule to give a sense of life in your bubble in 2020.

— What sorts of things – objects, images, etc. – would you include in your time capsule?

— During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, oral historians have been discussing how to continue their work from their home offices. Around the world, people have been interviewing others about their experience of COVID-19. Ministry for Culture and Heritage Historian (Audio-Visual Content) Emma Jean Kelly has prepared a really useful guide for conducting such interviews. You can view this here. Emma has also produced a more advanced guide which could support senior students conducting more in-depth research into this topic. She has been talking to experts and experimenting with gear at home to create the best possible recordings via online recording platforms. Emma has some excellent suggestions here: How to record oral histories at home in your bubble.

— Consider some of the suggestions from these resources to help you record your experiences of life in the time of lockdown. You could:

- keep a diary and use this as a script for an audio-visual recording. Think about some of the highs and lows of your experience of COVID-19.

- interview the other people in your bubble.

C. Iwi responses to COVID-19

During the 1918 flu pandemic, the Māori death rate was more than eight times that for Pākehā. Many iwi were determined to do all they could to avoid a repeat of such devastation in 2020. One response as New Zealand moved into alert level 4 in March 2020 was the establishment of iwi-organised and -led checkpoints to enforce level 4’s key requirement of avoiding any non-essential travel. Just as New Zealand had closed its borders to international travellers, some iwi adopted a similar response to safeguard those living within their own rohe (area).

Te Whānau-ā-Apanui in the Bay of Plenty and Ngāti Porou on the East Coast worked with local decision-makers and police to support limits on travel, protect at-risk communities, and uphold public health controls. Tina Ngata, one of the organisers of a checkpoint on the East Coast, explained that those running these checkpoints in areas with significant Māori populations were acutely aware that Māori were particularly affected by past epidemics. The checkpoints established in 2020 have precedents. During the influenza pandemic of 1918, entry points to manage traffic were set up to limit the spread of influenza, for example at Coromandel and at Te Araroa on the East Coast.

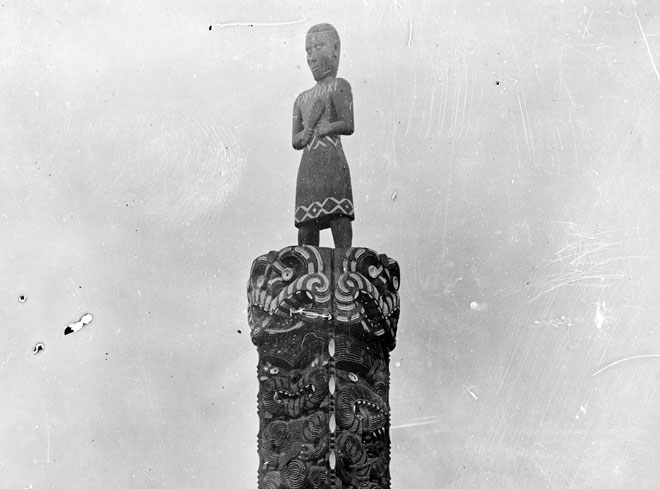

Alexander Turnbull Library, APG-0786-1/2-G

This memorial at Te Kōura marae, between Ōngarue and Taumarunui, was made by renowned carver Tene Waitere of Ngāti Tarāwhai as a memorial to those who died in the influenza epidemic of 1918.

This Spinoff article, Community checkpoints are an important and lawful part of NZ’s Covid response, presents the case for why these checkpoints are a valid response to the threat of COVID-19 in 2020.

Not everyone has agreed with these actions. The lobby group Hobson's Pledge started a nationwide petition calling for the end of iwi-led ‘vigilante’ checkpoints. The group's main concern was that iwi were taking the law into their own hands. If iwi felt entitled to do this, then what was to stop other citizens doing the same? Some opposed to these checkpoints spoke to local media and talkback radio to complain about what they called ‘roadblocks’ and how they had felt intimidated by some of the volunteers at these checkpoints. Photos appeared in the press of a checkpoint at Murupara, of two volunteers were shown in full gang regalia A spokesperson for the checkpoint, Te Akauroa Miki, highlighted that their ‘volunteers came in all shapes and sizes’ and that they did not ‘sugar coat things when our community is at risk.’ When the all went out for volunteers, three different gangs put aside their differences to help. Miki believed that how these volunteers dressed was ‘up to them’ but maintained that all volunteers approaching vehicles were ‘kind, have a smile and donned in a hi-viz reflective vest.

Those initiating the petition felt that the police and others in authority were turning a ‘blind eye to lawbreaking’ by ‘vigilante iwi-gangster road-blockers’, which ‘looks like one law for Maori and another law for everyone else.’ The Commissioner of Police, Andrew Coster, wrote that the iwi checkpoints were about ‘safety and discretion’. Either way, these actions provoked much comment on talkback radio and social media.

It is worth noting other areas where locals pushed back on those from outside their area travelling on non-essential business during levels 3 and 4. Residents of the small Wairarapa beachside communities of Riversdale and Castlepoint observed an influx of people in apparent violation of level 3 rules. Hayden Meads, owner of the beach store at Riversdale, was upset that people were making the 150 km trip from Wellington to visit their baches or go surfing. He said the community felt less safe under alert level 3 than it did under level 4, and locals were telling Wellingtonians to keep out. Wairarapa had become coronavirus-free on April 14 and ‘locals wanted to keep it that way’. The many older people in the community were more vulnerable to infection. Keeping visitors away was important, as it ‘protected their local community.’

Further up the coast at Castlepoint, store owner Joe Vermeer also observed that as soon as level 3 came into force they had a rush of visitors. A group of surfers from outside the area were told to ‘go home by locals. They were from Wellington, so they were told to leave.’

They complied, Vermeer said. While there were no checkpoints or roadblocks in place, those living in these communities were willing to take direct action and tell visitors to ‘get out of town’ to protect their own. There was little, if any, media backlash against these actions.

— During alert levels 3 and 4, travel was severely limited. People living in isolated parts of the country took a number of actions to stop motorists arriving and potentially spreading the disease to their communities. If you were an iwi leader in an isolated area, or the mayor of a small town, what would you do to keep your community safe?

— Imagine you are a reporter for a local newspaper or radio station in an area where iwi have set up checkpoints to restrict travel in the region. For a special feature you have been asked to consider alternative views on this approach by:

- interviewing an iwi leader to find out why they believe it is necessary for them to establish checkpoints on key roads into your area. Ask this person what they would say to someone who argued that such checkpoints are illegal.

- Interview someone else opposed to the use of checkpoints in this way. Ask this person – or a signatory to the petition promoted by Hobson’s Pledge – why they believe these actions of iwi are intimidating and illegal.

- What are your own views on these actions?

D. Planning for the future

The historian Geoffrey Rice, who studied the 1918 flu pandemic, found that there was one useful aftermath of the pandemic – the Health Act 1920. This made sure our public health services were better organised after the pandemic than they had been before.

- If you were in charge of the New Zealand health system now, what changes would you make to ensure we were better prepared for a national medical emergency in the future?

Community contributions