The government immediately reset its priorities on the outbreak of war in August 1914. Everything else was subordinated to winning the war. The public service, responsible for enacting the government’s wishes, would have to both refocus its energies on new wartime activities and find a way to carry on with business as usual in the face of declining manpower and public revenue and rising costs.

Departmental war work

As the public service shifted quickly into war mode, many departments found themselves with new responsibilities. The Defence Department shouldered the heaviest burden, organising the recruitment, training, and outfitting of the country’s soldiers, and later also enforcing the conscription process. The Railways Department transported men to camp, around the country on leave, and to the wharves for embarkation. The Post and Telegraph Department acted as an information bureau and point of contact between the government, soldiers and their families, and took charge of press and mail censorship. The Police Department monitored enemy aliens, helped track down those who tried to evade military service, and kept the peace. The Discharged Soldiers’ Information Department, established in 1915, served the needs of men returning from the war.

The commandeer also placed great demands on the public service. The Department of Imperial Government Supplies created to manage the process drew staff away from other departments. Agriculture Department staff took charge of inspecting goods for export, while their Mines Department counterparts inspected scheelite, which the British used to make armaments.

The Public Trust took charge of administering soldiers’ wills and property, while Government Insurance was kept busy processing and paying out life insurance claims for deceased soldiers. The Department of Public Health oversaw the care of soldiers who returned to New Zealand with injuries requiring longer-term treatment.

Business as usual?

There was no appreciable drop in performance during the first two years of the war, with departments taking pride in their ability to keep going as usual despite the diminishing numbers of men. The challenges were only to grow, with revenue and manpower dropping simultaneously. Customs revenue and railways profits were important sources of government income, and both fell substantially from the early months of the war while the costs of labour and materials steadily increased. Government borrowing, too, became difficult as the London money market rebuffed requests for loans from New Zealand to focus on funding the British war effort. The New Zealand government was able to raise some revenue through internal borrowing, but the overall picture was bleak. This would be a period of austerity and retrenchment, with the government committed to preventing the public service from growing except in the service of the war effort.

The government initially reprioritised manpower and expenditure by cutting back on large infrastructural projects. A major development of rail facilities funded in the 1914 estimates was suspended indefinitely soon after the war began. The Public Works Department, responsible for building roads and railways and undertaking other large-scale development work, was one of the largest recipients of government expenditure and borrowing. The department cut its programme dramatically, completing current projects but spreading its 1914 appropriation over several years.

Public Service Commissioner Donald Robertson’s programme of reform and rationalisation, begun in 1913, soon ground to a halt. ‘With 1319 officers absent with the Expeditionary Forces the time has not been opportune for readjustments of staff, and important reforms have been temporarily arrested’, he reported in 1916. ‘The number of officers with the Expeditionary Forces represents approximately 45 per cent of the total number of single men of military age in the Public Service.’ [1]

By 1918, all the larger departments had lost a significant proportion of their permanent staff to the war effort. Six departments had more than a third of their staff absent on military service: Native, Pensions, Public Trust, State Advances, State Fire Insurance and the Dominion Laboratory. Another eight had at least a quarter away: Audit, Government Insurance, Justice, Lands and Deeds, Lands and Survey, Public Works, Railways and the Registrar-General’s Office. The large Post and Telegraph Department had contributed 22% of its staff.

Public servants at war

The public service embraced the principle that, wherever possible, its employees should be released to join the NZEF. They would serve the government’s war aims more directly at the front than by remaining at their posts. The departments promised to keep the men’s positions open for them, replacing them with temporary workers. Staff who enlisted would also retain their seniority and superannuation rights, which would be subsidised by the department. The public service commissioner ruled that absent staff would be automatically considered for any promotion and would continue to accrue leave at full pay.

The only department which refused to give its staff leave was the Police – constables were needed at home to keep the peace. Policemen had to resign in order to enlist, and would lose their benefits, seniority and position on the salary scale if they ever rejoined the Force. In practice, Parliament voted to reinstate these conditions for returning officers at the end of the war.

Feeling the pinch

Until 1916, the public service was able to maintain most services by cutting leave and extending working hours. Then conditions began to tighten. Like many other enterprises, departments were finding it harder and harder to function with fewer staff. The public service found itself competing for staff with better-paying private employers. Robertson noted that the large number of enlistments was creating ‘exceptional difficulties’. [2]

The introduction of conscription in August 1916 added to the problem, because the Defence administration had to be expanded dramatically to cope with the new work, drawing staff away from other departments. Conscription itself would also remove more men from the public service – and diminish departmental influence over who should stay behind in the public interest. The government did its best to keep the remaining staff by blocking retirements and preventing transfers between departments from October 1917, but the pressure remained. Most departments made few requests for exemptions from military service. Railways, however, appealed against the calling-up of 569 of 826 staff balloted between November 1916 and May 1917. These call-ups were all deferred. In total 810 men were exempted on the grounds that they were performing ‘Public Services’, but it is unclear if all these men were public servants.

The public was mainly affected by the diminishing numbers in small ways. Some public services, especially in rural areas, began to atrophy. The Agriculture Department agonised that the depletion of its army of inspectors was diminishing its ability to influence the agricultural sector. In the absence of inspectors there was no practical threat of prosecution, so farmers grew lax in uprooting noxious weeds and rabbits got out of control, especially in Otago and Southland. The commandeer was absorbing so much of inspectors’ energies that they could not maintain their normal work. High dairy returns incentivised farmers to run more stock instead of growing wheat, and food prices crept up as a result. The department also worried that the commandeer was encouraging farmers to butcher potential breeding stock.

Other departments also complained that staff attrition was hindering their ability to do their work. The Mines Department noted in 1919 that the war had so diminished its staff that its functions ‘cannot be adequately and satisfactorily performed’. [3] The number of police officers fell from 1916 despite the appointment of temporary constables. The police training college closed in December 1916 for want of recruits.

The greatest pressure fell on the two largest departments, Post and Telegraph and Railways, which struggled to maintain essential services throughout the country. Post and Telegraph had a heavy load of war work on top of a steady increase in the volume of mail. Railways had lost thousands of men to military service, and by the end of 1916 5000 special military trains had run in addition to normal services. Civilian passenger numbers and freight volumes were dropping, while the costs of materials and labour were soaring as both became scarce. Sooner or later, something would have to give.

Temporary employees

The public service did its best to ameliorate these difficulties by employing temporary staff, especially in the departments most closely involved in the war effort. Defence had one temporary staff member in 1914 and 863 in 1918. Internal Affairs, with its responsibility for the Government Statistician’s Branch, had climbed from 32 to 608, and Public Health, managing soldiers’ hospitals, from 80 to 228. The Public Trust had no temporary employees in 1914 but 179 in 1918. Public Works, by contrast, had 6899 in 1914 and just 90 in 1918. Some of these new employees were recruited from the general workforce, while others were men rejected for military service on medical grounds but able to perform clerical ‘Home Service’.

Many temporary employees had neither the skills nor the experience to carry a full workload. ‘The loss of the services of permanent officers of experience is felt in every office in the Dominion,’ noted the head of Post and Telegraph in 1918, ‘and as the same skill and local knowledge cannot be expected of the temporary substitutes, it is felt seriously. Controlling officers, working with depleted and inexperienced staffs, find their duties most exacting and responsible and their executive abilities tried to the utmost.’ [4]

Woman-powering

Many of the temporary employees were women. Uncommon at the beginning of the war, the employment of women quickly gained popularity as a means of keeping the public service going. By 1916 women were filling gaps in many professions, including banking and other clerical occupations, so the public and private sectors were competing for their services. In the United Kingdom and other combatant countries women were being drawn more actively into agricultural and industrial work.

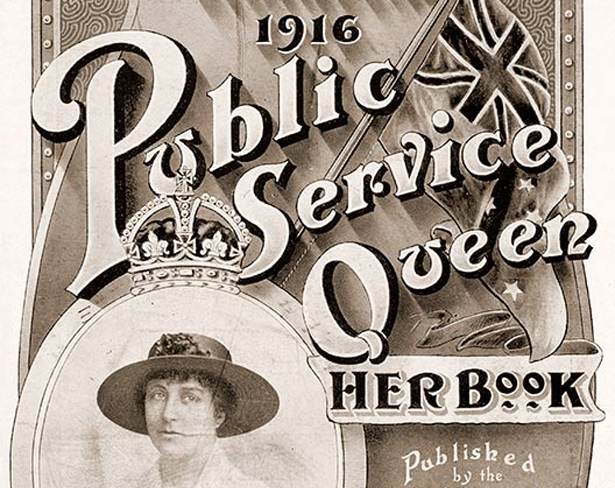

Public Service Queen

Thirty-nine-year-old Isabella Palmer was one of eight women nominated for election as the Queen of Canterbury in January 1916. The candidates were not ‘beauty queens’ in the modern sense, but figureheads for sections of the community. Isabella was nominated as ‘Public Service Queen’ – the candidate representing public servants and local-body employees. Read more.

Employing women in the public service was a logical step, but a conceptual shift. ‘The employment of women has assumed a new aspect,’ Robertson wrote in 1916, ‘and Departments which prior to the war objected to female officers are now utilising women for such work as assisting auditors, ledger work, and other minor accounting and clerical work.’ Among these departments was Defence, which had previously preferred not to employ women ‘partly owing to want of proper accommodation and partly owing to hesitation on the part of the Department.’ [5]

Departments such as Defence on which the burden of war work weighed most heavily were probably the first to welcome women into their offices, however hesitantly. These organisations probably had the greatest culture of expectation that male staff would enlist – and they also needed to expand rapidly. The Post and Telegraph Department, likewise, increasingly turned to women to work on counters and in telephone exchanges, roles in which they already had a niche in 1914. Robertson noted that by 1916, 513 women had been appointed as temporary employees across the public service in place of men who had enlisted. Women were soon employed in many departments. Robertson reported in 1918 that 873 of the 1207 public servants working on directly war-related activities were women. Overall there were now 4153 women in the public service, compared to 1826 before the war. The proportion of female teachers increased as men left to fight, reinforcing an existing trend. By the end of 1917, 750 male teachers had enlisted. In 1914, 63% of teachers were women; in 1918, 72%.

In 1915, as the number of female staff began to climb, Robertson appointed Daisy E. Platts-Mills as medical officer to the women of the public service. She inspected government offices to ensure they had suitable facilities for women, including workspace, cloak and toilet rooms and rest-rooms (sick bays). The Post and Telegraph and the Public Trust were models in this respect, while the relevant Defence offices were especially overcrowded and uncongenial. Several departments appointed their own matrons, while others elected welfare committees to handle women’s concerns. Platts-Mills expressed concern that the influx of female public servants in Wellington had severely strained the available private accommodation – the government should step in to protect young women from the ‘difficulties and temptations which are detrimental alike to health and to morals’. Robertson arranged financial help for organisations such as the YWCA which supported ‘young girls living away from home’. [6]

Few of the incoming women had any experience of or training in office work. Director of Recruiting David Cossgrove, who supervised the issuing of call-up notices, described his female typing staff as enthusiastic rather than competent. They were ‘of the very poorest quality’, he complained in 1919, many of them ‘school-girls learning typing and their work bristled with errors.’ [7] Government Statistician Malcolm Fraser was also frustrated by their inexperience, but noted that ‘all were imbued with an ardent patriotic desire to “do their bit” in the crisis facing the country, and looking back at what was accomplished under the trying conditions it must be admitted that they did wonders.’ [8]

Women would, however, remain at the bottom of the career ladder. Cossgrove asserted in 1918 that ‘women clerks cannot withstand the strain in responsible positions – quite apart from the fact that my experience has been they have not the ability to deal with responsible work in this branch.’ [9] Robertson noted the additional problem that male officers would refuse to be managed or trained by a woman. The average annual pay for female public servants in 1917 was £117, compared to £173 for males, an inequity the PSA fought to remedy during the war years, without success.

Robertson noted that, despite their lack of experience and departmental ‘hesitation’, the employment of women had been a successful experiment: ‘the Commissioners record that women are now satisfactorily performing work which Departments would have hesitated to entrust to them before the war. The zeal, diligence, and good conduct of the large number of women, of whom the greater proportion had no office experience before joining the Service, merits praise.’ [10]

The cost of living

The cost of living climbed steadily through the war, with rising prices for food and goods pushing down purchasing power. In April 1916 the government suspended its regular public service pay regrading on the grounds that too many staff were away on active service – there would be no pay increases until the war ended.

The government tackled the cost of living problem by awarding public servants a one-off bonus in each of the remaining years of the war. When these were announced, some newspapers complained that the government was indulging public servants at the expense of the rest of the community. The Public Service Journal responded that public servants were in general worse paid then their private sector counterparts, and their fixed incomes made them more vulnerable to price rises.

Public servants felt the bonuses were too small to make an appreciable difference to their financial circumstances, and many struggled with the rising cost of living. This quickly became the most pressing issue facing the public service unions. In November 1916 the Public Service Association, the Post and Telegraph Officers’ Association, the three railway unions and the New Zealand Educational Institute teamed up to form a Council of New Zealand State Service Associations with a total membership of 26,000. A deputation from the council which met Acting Prime Minister James Allen in June 1917 urged the government to work harder to hold down the cost of living. The government responded with another war bonus; it had little else to offer. The public service, like the rest of the country, would have to knuckle down until better days arrived.

Endgame and aftermath

By 1918 shrinking manpower and revenue was forcing some hard decisions upon the public service. The Post and Telegraph Department cut back its services from 1 July as the conscription of the Second Division – men with wives and families – began, tipping the workload beyond what the remaining staff could absorb. The department reduced post office opening hours and the frequency of mail delivery. This reorientation allowed more women to be employed, as working at night was thought unsuitable for them.

Despite its many successful appeals, the Railways Department was also affected by the introduction of conscription. From November 1916 it experimented with ways to meet the needs of the NZEF while maintaining the railway timetable. In May 1917 it cut services in order to release more workers. By now coal shortages were being felt, and coal was formally rationed from October 1917. Although passenger numbers and freight volumes were dropping dramatically, the coal and manpower shortages and rising maintenance costs severely tested the viability of the rail system. Reduced train timetables prioritised moving troops and serving the needs of the war effort. The coal shortage also exacerbated the shipping shortages which were inhibiting farming exports and economic development.

The November 1918 Armistice did not immediately relieve the strains on the public service. The influenza pandemic struck simultaneously, hitting public servants as hard as every other part of the community. Several departments had 60% of their staff on sick leave at one time, and 114 public servants died. It took three months for most departments to get back on top of their work.

The public service slowly returned to normal over the next two or three years. A continuing rise in the cost of living was offset by the reintroduction of regrading in early 1919. Railway timetables returned more or less to the pre-war norm in December 1919, as did postal services as men returned from the NZEF. Demobilised men gradually returned to work across all departments, while former soldiers were given preference for new positions. The number of temporary employees dropped from 2089 in April 1919 to 583 in November 1921, when 159 were still employed on specifically war-related work such as auditing, pensions and soldier settlement.

Although he praised the contribution of female staff at the end of the war, Robertson’s view of the place of women in the public service had not changed since he excluded them from entrance examinations in 1913. In normal circumstances, he considered, ‘the employment of women as clerks is satisfactory only to a limited extent’. Men must be encouraged to join the public service, and promoting women – who would only marry and leave – would be ‘likely to have far-reaching results’. If they were to be employed in the public service, women should focus on shorthand and typewriting, which they ‘have made practically their own.’ [11] By 1924 only four female clerks remained in the Defence Department.

A good war?

Overall, the public service successfully met the unprecedented demands of the war on its resources and ingenuity. Manpower shortages were met by reconfiguring and reducing services, and by tapping into under-utilised sections of the labour market – women especially. High costs and limited resources forced the prioritisation of activities, with inessentials cut to the bone. New departments were created and several existing departments expanded massively. With a few exceptions, government services were successfully adapted and maintained in trying circumstances.

Number of permanent and temporary employees by department

| 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Permanent/ | Permanent/ | Permanent/ | Permanent/ | Permanent/ Temporary | |

| Agriculture, Industries, and Commerce | 427 / 756 | 440 / 864 | 458 / 756 | 491 / 765 | 497 / 682 |

| Audit | 60 / 0 | 72 / 2 | 87 / 12 | 90 / 27 | 102 / 102 |

| Crown Law | 9 / 0 | 9 / 0 | 10 / 0 | 9 / 0 | 8 / 0 |

| Customs | 238 / 1 | 236 / 2 | 254 / 9 | 272 / 25 | 276 / 29 |

| Defence | 83 / 30 | 91 / 100 | 114 / 275 | 118 / 598 | 83 / 863 |

| Education and teachers* | 5309 / 47 | 6165 / 26 | 6290 / 40 | 6287 / 61 | 6424 / 68 |

| Government Insurance | 138 / 2 | 133 / 12 | 145 / 9 | 151 / 9 | 158 / 33 |

| Immigration | 6 / 0 | 7 / 0 | 6 / 0 | 6 / 0 | 5 / 0 |

| Internal Affairs (a) | 279 / 36 | 370 / 79 | 429 / 138 | 493 / 482 | 544 / 608 |

| Justice (b) | 215 / 60 | 227 / 33 | 234 / 24 | 224 / 25 | 235 / 41 |

| Labour | 66 / 13 | 77 / 18 | 86 / 12 | 89 / 23 | 81 / 17 |

| Lands and Deeds | 97 / 1 | 100 / 0 | 106 / 4 | 112 / 10 | 114 / 12 |

| Land and Income Tax | 72 / 2 | 70 / 0 | 73 / 0 | 81 / 0 | 94 / 5 |

| Land for Settlements | 3 / 0 | 3 / 0 | 3 / 0 | 3 / 0 | 3 / 0 |

| Lands and Survey | 438 / 146 | 480 / 141 | 504 / 88 | 512 / 94 | 501 / 99 |

| Marine and Inspection of Machinery | 173 / 19 | 175 / 4 | 171 / 5 | 177 / 11 | 175 / 14 |

| Mental Hospitals | 632 / 80 | 667 / 176 | 706 / 7 | 711 / 9 | 656 / 13 |

| Mines | 99 / 2 | 99 / 3 | 101 / 5 | 103 / 9 | 102 / 13 |

| National Provident and Friendly Societies | 18 / 4 | 26 / 7 | 27 / 10 | 29 / 17 | 32 / 21 |

| Native | 54 / 4 | 62 / 6 | 72 / 9 | 68 / 15 | 71 / 31 |

| Pensions | 27 / 0 | 28 / 1 | 33 / 5 | 41 / 19 | 48 / 55 |

| Police* | 6 / - | 6 / - | 4 / - | 4 / - | 3 / - |

| Post and Telegraph | 7939 / 1270 | 8305 / 966 | 8787 / 1530 | 9313 / 1842 | 9268 / 1263 |

| Printing and Stationery | 308 / 276 | 340 / 1 | 361 / 235 | 379 / 197 | 390 / 176 |

| Prisons | 142 / 0 | 165 / 49 | 165 / 64 | 201 / 62 | 188 / 65 |

| Private secretaries | 8 / 0 | 8 / 0 | 8 / 0 | - | 6 / 0 |

| Public Health, Hospitals, Charitable Aid | 66 / 80 | 66 / 32 | 75 / 29 | 82 / 144 | 8 / 228 |

| Public Service Commissioner's Office | 15 / 0 | 14 / 1 | 16 / 0 | 16 / 0 | 21 / 0 |

| Public Service Superannuation | 5 / 1 | 6 / 0 | 6 / 0 | 8 / 0 | 7 / 1 |

| Public Trust | 204 / 0 | 235 / 20 | 276 / 21 | 31 / 83 | 377 / 179 |

| Public Works | 531 / 6899 | 657 / 103 | 708 / 91 | 676 / 104 | 655 / 90 |

| Railways* | 14,213 / - | 14,176 /- | 14,614 / - | 14,968 / - | 13,708 / - |

| Stamps | 32 / | 31 / 2 | 37 / 3 | 38 / 10 | 55 / 17 |

| State Advances | 53 / 0 | 55 / 1 | 58 / 7 | 60 / 9 | 58 / 14 |

| State Fire Insurance | 56 / 1 | 64 / 4 | 73 / 15 | 72 / 18 | 69 / 35 |

| Tourist and Health Resorts | 126 / 323 | 148 / 307 | 152 / 267 | 155 / 253 | 147 / 260 |

| Treasury | 55 / 0 | 55 / 5 | 58 / 16 | 64 / 16 | 62 / 22 |

| Valuation | 92 / 27 | 108 / 23 | 108 / 9 | 106 / 12 | 103 / 19 |

| TOTAL | 32,294 / 10080 | 33,976 / 2988 | 35,415 / 3695 | 36,528 / 4949 | 35,415 / 5076 |

* Figures for teachers, Police and Railways temporary staff are unavailable

(a) Internal Affairs includes Census and Statistics, Dominion Museum, Dominion Laboratory, and Registrar-General

(b) Justice includes Cook Islands and Patent

Download a spreadsheet showing references and more statistics.

Public service military contribution by department

| 1914-15 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

On active service / | On active service / | On active service / | On active service / | |

| Agriculture, Industries, and Commerce | 21 / 3 | 34 / 0 | 62 / 5 | 80 / 3 |

| Audit | 12 /1 | 15 / 1 | 18 / 0 | 23 / 2 |

| Crown Law | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Customs | 14 / 0 | 34 / 2 | 48 / 2 | 58 / 3 |

| Defence | 6 / 0 | 17 / 0 | 18 / 1 | 24 / 1 |

| Education and teachers | 225 / 39 | 478 / 38 | 867 / 55 | 1000 / 58 |

| Government Insurance | 13 / 1 | 23 / 3 | 35 / 0 | 44 / 2 |

| Immigration | 2 / 0 | 1 / 0 | 1 / 1 | 0 / 0 |

| Internal Affairs (a) | 6 / 0 | 20 / 2 | 33 / 2 | 38 / 4 |

| Justice (b) | 5 / 2 | 31 / 7 | 46 / 3 | 44 /3 |

| Labour | 5 / 0 | 7 / 1 | 11 / 2 | 14 / 1 |

| Lands and Deeds | 8 / 1 | 17 / 1 | 21 / 0 | 25 / 3 |

| Land and Income Tax | 3 / 0 | 13 / 0 | 12 / 0 | 15 / 0 |

| Land for Settlements | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lands and Survey | 27 / 10 | 48 / 6 | 82 / 6 | 102 / 9 |

| Marine and Inspection of Machinery | 4 / 0 | 7 / 0 | 17 / 0 | 18 / 2 |

| Mental Hospitals | 25 / 5 | 65 / 3 | 86 / 7 | 92 / 6 |

| Mines | 3 / 0 | 4 / 0 | 9 / 0 | 13 / 2 |

| National Provident and Friendly Societies | 2 / 0 | 3 / 1 | 4 / 0 | 5 / 1 |

| Native | 4 / 0 | 11 / 3 | 16 / 2 | 19 / 0 |

| Pensions | 3 / 1 | 7 / 1 | 8 / 1 | 13 / 0 |

| Police | 2 / 0 | 1 / 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Post and Telegraph | 170 / 27 | 704 / 39 | 1175 / 72 | 1481 / 81 |

| Printing and Stationery | 5 / 0 | 18 / 1 | 33 / 4 | 47 / 7 |

| Prisons | 5 / 0 | 7 / 1 | 26 / 1 | 21 / 1 |

| Private secretaries | 1 / 0 | 2 / 0 | 3 / 0 | 2 / 0 |

| Public Health, Hospitals, Charitable Aid | 3 / 0 | 14 / 0 | 14 / 0 | 11 / 0 |

| Public Service Commissioner's Office | 1 / 0 | 2 / 0 | 3 / 0 | 3 / 0 |

| Public Service Superannuation | 0 | 0 | 1 / 0 | 1 / 0 |

| Public Trust | 15 / 2 | 43 / 5 | 69 / 6 | 108 / 13 |

| Public Works | 32 / 5 | 76 / 4 | 126 / 8 | 138 / 5 |

| Railways | 258 / 51 | 864 / 101 | 3000 / 162 | 4250 / 127 |

| Stamps | 3 / 0 | 6 / 0 | 7 / 1 | 11 / 0 |

| State Advances | 8 / 0 | 11 / 0 | 16 / 1 | 19 / 0 |

| State Fire Insurance | 7 / 0 | 16 / 1 | 16 / 3 | 23 / 0 |

| Tourist and Health Resorts | 7 / 1 | 14 / 0 | 21 / 2 | 26 / 0 |

| Treasury | 14 / 2 | 15 / 0 | 16 / 2 | 17 / 1 |

| Valuation | 8 / 0 | 12 / 1 | 16 / 1 | 16 / 1 |

| TOTAL | 927 / 162 | 2640 / 223 | 5936 / 350 | 7801 / 336 |

(a) Internal Affairs includes Census and Statistics, Dominion Museum, Dominion Laboratory, and Registrar-General

(b) Justice includes Cook Islands and Patent

Download a spreadsheet showing references and more statistics.

Further information

This article was written by Tim Shoebridge and produced by the NZHistory team. It was commissioned by the State Services Commission. A fully footnoted version is available to download as a pdf here.

Primary sources

The annual reports of government departments for the years 1914-19 published in the Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives and issues of the Public Service Journal (1916-18) provided most of the information for this article. Key information was also drawn from the following reports at Archives New Zealand:

- David Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916-1918’, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2

- Malcolm Fraser, ‘War work of the Census and Statistics Office’, IA1 1652 26/125

Books

- Alan Henderson, The quest for efficiency: the origins of the State Services Commission, State Services Commission, Wellington, 1990

- Bert Roth, Remedy for present evils: a history of the New Zealand Public Service Association from 1890, New Zealand Public Service Association, 1987

Notes

[1] Public Service Commissioner annual report, AJHR, 1916, H-14, p. 2

[2] Public Service Commissioner annual report, AJHR, 1916, H-14, pp. 1-2

[3] Mines Department annual report, AJHR, 1919, C-2, p. 1

[4] Post and Telegraph Department annual report, AJHR, 1918, F-1, p. 4

[5] Public Service Commissioner annual report, AJHR, 1916, H-14, p. 11

[6] Public Service Commissioner annual report, AJHR, 1920, H-14, pp. 30-2

[7] David Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916-1918’, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2, Archives New Zealand, p. 10

[8] Malcolm Fraser, ‘War Work of the Census and Statistics Office’, p. 18

[9] D.C.W. Cossgrove evidence to the Defence Expenditure Commission, p. 1590, LE1 682 1918/14 pt 4, Archives New Zealand

[10] Public Service Commissioner annual report, AJHR, 1918, H-14, p. 2

[11] Public Service Commissioner annual report, AJHR, 1919, H-14, pp. 3-4

Community contributions