Reliable statistics are one of the most fundamental tools for understanding New Zealand’s military contribution to the First World War. Yet widely varying figures for even the number of New Zealand servicemen are routinely quoted in newspapers, on websites, on television, in official war histories, and in politicians’ speeches. Similar confusion surrounds such basic issues as casualty numbers and even how we might define a ‘New Zealand’ soldier.

This aim of this feature is to provide some reliable basic statistics and explain how we arrived at them.

Key statistics

Click on numbers to find out more

| 98,950 | served in New Zealand units overseas |

| 80% | were volunteers |

| 20% | were conscripted |

| 2227 | served in Maori units |

| 461 | came from the Pacific Islands |

| 550 | nurses served in the NZEF, 18 died |

| 7036 | served in New Zealand |

| 9% | of the population served |

| 0.9% | New Zealand units as a proportion of the British forces |

| 286 | men were imprisoned for rejecting military service |

| 6400-7900 | men refused, objected to, or avoided military service |

| 18,058 | total deaths |

| 2779 | died during the Gallipoli campaign |

| 2111 | died during the Somme offensive |

| 837 | died during the Messines offensive |

| 1796 | died during the Passchendaele offensive |

| 5 | were executed |

| 41,317 | occurrences of injury or illness |

| 501 | prisoners of war |

Who should we count?

Public demand for reliable statistics grew during the war as people sought to quantify the country’s ‘contribution’ for administrative, educational, political or personal reasons. The Defence Department tabulated monthly returns of men entering camp, embarking for overseas, killed, wounded, and so on, and when the war ended it was able to quickly collate much of this material for publication. In February 1919 it published War, 1914–1918. New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Its provision and maintenance, a volume of 42 statistical tables outlining most aspects of military service. Here you could find out the number of reinforcements sent overseas each month, the numbers of nurses, horses, men called up under conscription, the number and type of honours awarded to New Zealanders, and much more. The department distributed Provision and maintenance to newspapers and government agencies across the country, as well as to overseas governments and organisations. This book still underpins our understanding of New Zealand’s military involvement in the First World War.

Readers interpreted the 42 tables according to their backgrounds and inclinations. The 1919 New Zealand official year-book stated that by November 1918 110,368 people had been ‘provided for foreign service’, ‘more than 10% of the Dominion's mean population in 1914’, while 100,444 had been ‘attested into the New Zealand Expeditionary Force’ and ‘left for service overseas’. [1] The Evening Post proclaimed that 124,211 men – more than half the country’s men of military age and one-ninth of the total population − had been ‘mobilised’, while 220,089 had been ‘put through the military machine’ and 135,184 had been called up under conscription. [2] Other newspapers reported that 117,175 men had been ‘called up and sent into camp for overseas service up to the date of the armistice’, so this figure too gained some currency. [3] What does all this mean?

A sense of competition with the other dominions, and with Australia in particular, appears to have played a part in the arrangement and interpretation of figures. Different presentation of the numbers could produce wildly varying impressions of the New Zealand war effort. The Defence Department supplied its most inflated figure to the publishers of Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–20. The total number of New Zealanders who served, by that reckoning, was 128,525. Comparison with the disaggregated figures in Provision and maintenance shows that many of these individuals had been called up but failed their medical inspection, while others had undertaken Home Service in New Zealand or joined other imperial units. This exercise demonstrated the fluidity of the figures according to who was interpreting them and for what purpose.

Provision and maintenance is a valuable book, but it was published before the final picture had emerged. By January 1920 the Defence Department had revised its personnel total for Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–20, and soon afterwards changed its mind about the casualty total listed in that publication. Some of the revised figures were published in the official Roll of honour in 1924 and in Lieutenant-Colonel John Studholme’s Record of personal services during the War of officers, nurses, and first-class warrant officers; and other facts relating to the NZEF (Wellington, 1928), but the original Provision and maintenance figures have retained their influence and currency. As time went by the Defence Department disseminated the new and old figures in various combinations when asked for them, making disentangling them more difficult. [4]

These problems of definition and categorisation, and of competing figures, are still with us.

What is a ‘New Zealand serviceman’?

To address this question, we must first understand and define our terms of reference. The key is to decide who should be counted as a New Zealand serviceman (or woman) and who should not. Unfortunately, the obvious criteria of New Zealand birth or origin provide no clear basis from which to work.

In August 1914 the government created the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) as the New Zealand contribution to the British forces pitted against Germany and its allies. The NZEF was a small cog in the British Empire’s overall military machine, which also included national forces supplied by Australia, Canada, South Africa and other parts of the empire. A few additional New Zealand units were formally detached from the NZEF: the force occupying Samoa, the Engineer Tunnelling Company, the Wireless Troop, and the nurses. They were, however, part of the NZEF in all but name, and this feature uses ‘NZEF’ to refer to them all collectively.

The NZEF was not limited to men born in New Zealand but open to all British subjects, whichever part of the empire they hailed from. Any man of British extraction residing in New Zealand who was of military age and in good health could join the NZEF – and likewise, any New Zealand-born man residing in Britain, another dominion such as Australia or Canada, or a British Crown colony, protectorate or territory could join a local force. So the idea of ‘national’ expeditionary forces was purely administrative; they were funded and organised by the dominions as a contribution to the greater, British and imperial, whole, and were inseparable from and more or less interchangeable with their counterparts.

The number of NZEF soldiers born outside New Zealand demonstrates the extent to which it was as much an imperial as a ‘New Zealand’ force. Over a quarter of the Main Body, the largest group of soldiers to leave New Zealand’s shores, had been born in Britain or elsewhere in the British Empire. [5] Of the 145,624 men examined by the New Zealand military authorities between 1916 and 1918, 20,635 had been born in England, 8274 in Australia, 6279 in Scotland, and 1097 in other British possessions, not to mention continental Europe, the USA and elsewhere. [6] In 1935 the Defence Department calculated that 866 of the NZEF’s war dead – 4.8% of the total – had been born in Scotland, and the proportion born in England must have been considerably greater. [7] The NZEF was organised by the New Zealand authorities and funded by the New Zealand public, but it was made up of men from across the empire.

What, then, of New Zealanders who ‘served in other forces’? Should we add them to the NZEF totals? Provision and maintenance attempts to enumerate the numbers of New Zealand-born men who served in other imperial units, in an effort to create a ‘meta-New Zealand’ statistic of all serving New Zealanders, everywhere (though without deducting the non-New Zealand-born men who served in the NZEF). It added 1184 ‘miscellaneous’ personnel to the NZEF service figure, mainly men who left New Zealand on troopships to join imperial units in Britain (be they born in Britain, New Zealand, Australia, or wherever). It added another 3370 men ‘known to have left New Zealand and enlisted in British and Australian forces’, leaving the question open about how many others were ‘unknown’ to the Defence Department. The validity of the exercise was also undermined by a note that ‘no authentic information is to hand as to exact numbers’ of New Zealanders who had served in the Canadian and South African forces. [8] Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey have identified 2533 New Zealand-born men in the Australian Imperial Force through a database of Australian records, but it is impossible to know how many of them were among the 3370 who left New Zealand to enlist. [9]

The bottom line is that it was impossible to even estimate the total number of New Zealand-born personnel who served in other units, and, short of the compilation of a database of personal details of every Allied serviceman, this task is likely to remain impossible. The Defence Department’s practice of adding the 1184 and 3370 ‘known’ personnel to the NZEF total, therefore, skews the picture both of New Zealand’s service record and of the records of the imperial units in which they served (if all the unit numbers are combined to calculate total figures for all the British forces, these individuals are counted twice).

We are therefore unable to add the numbers of New Zealand-born recruits serving in non-NZEF units to the NZEF figures to create ‘meta-New Zealand’ data on all Kiwis, everywhere. The few partial statistics available are too patchy and piecemeal to give us even an indication of how many New Zealanders served across all the British Empire's military forces. We therefore need to treat the few available (and very approximate) figures for New Zealanders serving in imperial units with caution.

The soundest basis for calculating the total number of New Zealand service personnel, therefore, is to count only those who served in ‘New Zealand military forces’, and treat those in other units as a separate category.

New Zealand military service in the First World War

How many men and women served in the NZEF?

Turning to the NZEF itself, it is once again necessary to define what we mean by ‘service’. The Defence Department considered men who had served in a war zone or in a staging area overseas, or were aboard a troopship on their way to war on the day the Armistice was signed, to have been ‘on active service’, and we follow that practice. [10] Those who had enlisted but were still training in New Zealand were excluded from the ‘active service’ total.

Provision and maintenance considered that, on this definition, 99,260 individuals had been on active service – 92,860 in the main NZEF and 6400 in the smaller New Zealand units. Of this number, 550 were nurses.

The Defence Department reduced the active service total to 98,950 in January 1920, though its clerks sometimes gave out the number 99,500 in the early 1920s. The lower figure was included in Studholme’s Record of personal services during the War in 1928, and remains the most authoritative figure available from the documentary sources.

How many New Zealand servicemen volunteered, and how many were conscripted?

From August 1914 until September 1916, all NZEF recruits were volunteers. For the rest of the war men were ‘called up’ for military service under a ballot system, but volunteers continued to be accepted. To judge the proportions that were volunteers or conscripts, we must first calculate how many there were in each group.

By September 1916 the government had received 104,467 applications to serve in the NZEF, although many men applied more than once. Of these, 69,085 men had been accepted for service and sent to camp. A further 24,105 volunteers were processed between late 1916 and the end of the war, of whom 13,939 were sent to camp (a further 720 were under orders to proceed to camp when the war ended). This means that a total of 83,024 volunteers were sent to camp over the course of the war. Together with conscripts, 115,294 men in all were sent to camp during the war [11] (elsewhere the Defence Department gives the figure as 117,175). [12] The Defence Department concluded in the early 1920s that 220,089 men had volunteered or been balloted, a figure which presumably includes all those who were rejected on medical grounds or otherwise exempted. [13]

The Defence Department produced several conflicting figures for the total number of men called up under the conscription system between 1916 and 1918, but the most reliable appears to be 138,034. The Government Statistician’s figures from November 1919 record that 134,393 men were called up under the monthly ballot system between November 1916 and October 1918 (s. 10 of the Military Service Act). An additional 2876 men were called up under s. 34 of the Act, the so-called ‘family shirker clause’, by which the Defence Department could call up the sons of families in which no-one had volunteered. It also called up 213 men under s. 35 of the Act, by which men found not to have enrolled for the conscription ballot could be sent straight to camp without being balloted.

Men called up under conscription system, 1916-19 [14]

| Type of call-up | Number called up | Medically examined | Sent to camp | Embarked |

| Monthly ballot (s.10) | 134,393 | 121,519 | 32,270 | 18,838 |

| ‘Family shirkers’ (s.34) | 2876 | 1313 | 934 | 689 |

| Not enrolled (s.35) | 213 | 137 | 58 | 21 |

| Maori ballot | 552 | 116 | 99 | 0 |

| TOTALS | 138,034 | 123,085 | 33,361 | 19,548 |

Some men were granted exemptions, while a large proportion of other men were rejected as medically unfit, both at the point of enlistment and after they had entered camp. The accompanying table illustrates this process. Of the 138,034 men called up under the conscription system, only 19,548 ultimately left New Zealand for service abroad.

Of the 98,850 New Zealand personnel who served abroad, therefore, 79,302 (80%) did so as volunteers and 19,548 (20%) as conscripts.

How many Māori and Pasifika soldiers served?

In late 1914 the New Zealand government formed an ad hoc infantry unit called ‘The Maori (Native) Contingent’ composed of 500 Māori volunteers. It was reorganised in early 1916 as the ‘New Zealand Pioneer Battalion’, a combined Māori and Pākehā unit, and then again in September 1917 as an all-Māori (and Pasifika) unit, the ‘New Zealand Maori (Pioneer) Battalion’.

2227 Māori and 461 Pasifika, mainly from the New Zealand territories of the Cook Islands and Niue, served in these units. A further 176 Māori and 170 Pasifika were in training in New Zealand on Armistice Day. [16] During 1918 552 Māori were conscripted. [17]

Māori and possibly some Pasifika served in other NZEF and imperial units, but no data is available.

How many nurses served?

550 nurses served in New Zealand units during the First World War. [18] Some New Zealand women served in other imperial nursing units.

How many people ‘served’ in New Zealand itself?

The Defence Department managed two branches of military service within New Zealand during the First World War: the Home Service Branch and the Territorial Force.

Provision and maintenance records that the Defence Department employed 7036 men on ‘home service’. [19] In June 1917 the department created a Home Service Branch of the NZEF, a body of civilian workers to support the war effort in New Zealand by helping in training camps, forts, Defence offices, and anywhere else they were required. Volunteers and conscripts found unfit for military service but still capable of civilian work were posted to the Home Service Branch, then granted leave without pay until further notice. The Minister of Defence could advertise for Home Service men with certain skills to volunteer their services, but had no power to conscript them for such work (except, from July 1917, as punishment for an offence). When they presented themselves for work the volunteers’ enlistment in the Branch was reactivated – confusingly, they were said to have been ‘called up’ (they could not voluntarily resign from the service). They wore uniforms and were governed by the same rules as NZEF men serving overseas, but were based at home and served in purely support roles. [20]

The pre-war Territorial Force, with its associated cadet units and Defence rifle clubs, remained in place to defend New Zealand from the possibility, however unlikely, of direct enemy attack, and to provide an informal feeder service for the NZEF. The Defence Department recorded the strength of the Territorial Force at various times, but not the number of men who passed through it. Over the course of the war the strengths of both the Territorial Force and the cadet forces fluctuated between 24,000 and 28,000, while the rifle clubs had between 7200 and 8800. On average 32.6% of the Territorial Force transferred to the NZEF each year between 1915 and 1918 (many young men joined or were conscripted to the NZEF on turning 20). [21]

Home Service men and Territorials are distinct and separate groups from the NZEF serving overseas, and should be treated as a separate category of military service.

What proportion of the New Zealand population served in the NZEF?

Calculating the proportion of New Zealanders who served in the NZEF depends, as with much else, on who you include and which figures you select.

Provision and maintenance (Graph 1) plots embarkation figures as a percentage of the total population, and concludes that 9.2% of the population embarked on active service. The cited population figure – 1,089,825 – is the government statistician’s estimate for 31 March 1914, while the active service figure – 100,444 – includes the naval and aviation recruits who left New Zealand for service in British forces. [22] If you use the figure of 98,950, then 9.1% of the population left New Zealand on active service.

How big a part of the overall British military forces did the NZEF make up?

The official British statistics compiled at the end of the war record that, on 1 November 1918, the combined British military forces comprised some 3,226,879 personnel, of whom 29,831 were serving in the NZEF – around 0.9% of the total force. [23] (Provision and maintenance puts the total figure of NZEF personnel overseas on Armistice Day at 56,436, which includes staff at the NZEF bases in France, England, Palestine and Egypt). [24]

How many men refused to serve in the NZEF?

The Military Service Act 1916 required all men aged between 20 and 45 to register with the Defence Department, which made them liable to be called up in a conscription ballot. Eligible men could be exempted because of ill health, because they worked in an essential industry, or on a few other specific grounds; all others were legally obliged to serve in the NZEF.

Some men, known as conscientious objectors, refused to serve on the grounds of religious, political or philosophical objection to the war. The Military Service Act provided that only religious objections would be considered for exemption, and such men had to prove their case before a Military Service Board. Historian Paul Baker calculates that these boards collectively granted exemption to 60 conscientious objectors, while another 13 were offered exemption but refused it. [25] 286 men had been imprisoned for refusing military service by the end of the war. [25a] Baker estimates that another 350 men were willingly transferred to non-combatant branches of the NZEF after stating religious or philosophical objections to bearing arms. [25b]

Some balloted men failed to appear for their medical examination, the first phase of the recruitment process, or, having been deemed medically fit, failed to enter camp when ordered to do so. These men were initially given the benefit of the doubt, but once the Defence Department decided an individual was deliberately avoiding service he became subject to arrest, imprisonment and the loss of his civil rights for 10 years. Men who deserted from camp also fell into this category. The department had investigated 10,737 such defaulter/deserter cases by March 1919, and 4045 men had been gazetted as defaulters. 580 of these men were arrested, and arrest warrants for another 1133 were outstanding at the end of the war. This suggests that around 1700 men avoided military service by refusing to present themselves as required by the ballot (though individuals arrested more than once will be counted more than once). [26] Ultimately 2320 men were gazetted as defaulters, after 99 names had been deleted on appeal. These men were deprived of the right to hold an elected public office of any kind or vote for 10 years. [27]

The government statistician estimated that around 3500 – or at most 5000 – men never registered for the ballot. He based this figure on census, death, and immigration/emigration statistics. [28]

| Category of objector | Number of objectors (very approximate) |

|---|---|

| Men imprisoned for refusing all forms of military service, including Māori | 286 |

| Men who made ‘conscientious’ appeals to Military Service Boards, and who were exempt on religious or other grounds | 100 |

| Men who refused to bear arms but agreed to be transferred to non-combatant units | 350 |

| Number of conscripted men who failed to appear for medical inspection, failed to attend camp, or who deserted | 2155 |

| Men who never enrolled for conscription | 3500–5000 |

| TOTAL | 6400–7900 |

New Zealand casualties

Provision and maintenance tells us that there were some 58,000 New Zealand ‘casualties’ of the First World War, out of around 98,000 servicemen, of whom around 16,000 died and 41,000 were ‘wounded’. These straightforward-seeming figures, however, should be treated with great caution.

A ‘casualty’, from the NZEF’s point of view, was a person who had been removed from active service for some period of time and so was unavailable for service at the front. Its casualty lists therefore record not only those who had died or were being treated for illness or injury, but also those who were missing at the time the list was made, or had been taken prisoner by the enemy. The ‘wounded’ list, furthermore, counts instances of men being hospitalised for any reason, rather than just those ‘wounded’ on the battlefield. Therefore a man who was hospitalised for toothache or back pain on five occasions was potentially counted five times as ‘wounded’, and might appear again in the overall casualty total if he died while in uniform.

This section reviews methods of calculating New Zealand’s First World War fatalities and the more complicated question of counting the ‘wounded’.

How many New Zealand service personnel died during the First World War?

There are several ways to calculate the number of service personnel who died during the war.

The first is the number of enlisted personnel who between 5 August 1914 and 12 November 1918 were killed outright or died from injuries sustained in battle, illness, accidents and other causes. Provision and maintenance recorded 16,302 such deaths, but this figure was subsequently revised upwards. [29] In January 1920 the Defence Department gave the figure of 16,654 to the publishers of Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–20, but it soon realised that this, too, was incorrect. [30] Its final number, 16,697, was published in the official Roll of honour in 1924 and in Studholme’s Record of personal services during the War in 1928. [31]

The official New Zealand Roll of honour adds to this total the 964 men who died while still enlisted in the NZEF, or after their discharge from war-related causes, between 12 November 1918 and 31 December 1923, and the 505 men who died while training in New Zealand. This brings the total deaths to 18,166 as of 31 December 1923. [32]

The New Zealand government, however, subsequently changed the basis for its official roll of honour. It now follows the practice of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) in limiting its scope to ex-service personnel who died between 4 August 1914 and 31 August 1921 (many New Zealand ex-servicemen died of war-related causes after that date, but they are not counted among the country’s official war dead). In 1963–4 the Defence Department compiled a new roll of honour to be housed in the Hall of Memories at the National War Memorial. This appears to have been based on the names listed in the 1924 Roll of honour, minus the post-August 1921 names and with a few other minor revisions. [33] The official tally of war deaths was now 18,052. The roll of honour remains open to revision, and recently six individuals who died in the war’s early weeks or committed suicide shortly after its conclusion have been added, bringing the official total to 18,058.

Taking the number of personnel as 98,950, and the 16,697 who died between 1914 and 1918 as the most historically (rather than administratively) meaningful figure, then 16.9% of them died during the war.

How many nurses died during the First World War?

Twelve nurses died during the war, including 10 who drowned because of the sinking of the Marquette in 1915. [34] These deaths are included in the total death figures discussed above.

Counting campaign casualties

Calculating death figures for any campaign or battle is a complex and sometimes fraught exercise, and the figures tend to be only as good as the most recent in-depth research into them. The source material is often patchy and inconsistent, and needs searching interrogation to be properly understood. Collecting data on the battlefield was a piecemeal and difficult process, and casualties were sometimes reported a week or more after the fighting had taken place. Men reported as missing or captured were later located or reclassified as dead, further complicating the collection of accurate data.

Identifying the number who perished on the Somme, say, will depend both on the accuracy of the figures collected at the time and the dates at which you start and stop counting. Many of the men who died in the weeks following the New Zealand Division’s withdrawal from the front lines succumbed to wounds sustained in the field. Others died months and even years later, and attributing each death to a specific battle or phase of combat would be a major exercise in statistical forensics. These complexities make it necessary to set some limits on the span of a specific campaign or battle.

The figures for the Gallipoli campaign and the three major Western Front offensives involving New Zealand forces listed below are based on (a) estimates by the official medical historian Lieutenant-Colonel A.D. Carbery in 1921 derived from official casualty returns, (b) later revisions of those figures by subject experts, and (c) death statistics gleaned from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database.

How many New Zealanders died during the Gallipoli campaign?

The Roll of honour (1924) states that 2721 died during the Gallipoli campaign, of whom 1909 were killed in action, 606 died of wounds, 200 died of sickness, and six died of ‘other causes’. [35] The Commonwealth War Graves Commission database lists 2843 New Zealand personnel who died between 25 April and 20 December 1915; not all of these deaths will have been as a result of service at Gallipoli. A more recent individual analysis of the Gallipoli dead by historian Richard Stowers identifies 2779 New Zealand deaths during the campaign. [36]

How many New Zealanders died during the Somme offensive?

Carbery estimated in 1921 that there were 6743 NZEF casualties (killed, wounded and missing) as a result of the Somme campaign between 1 September and 7 October 1916 (though the artillery remained in the field until 27 October). Of these, 1095 were killed, 4943 wounded and 705 missing. [37]

Historian Andrew Macdonald puts the total casualty figure at 7959, comprising 2111 dead and 5848 wounded between 31 August and 25 October 1916. He therefore assesses the casualty rate at 53% of the 15,000 men who began the campaign. [38] Macdonald bases his death figure on a study of individual deaths during the campaign, omitting men who died of illness or injury unrelated to the Somme offensive. [39]

How many New Zealanders died during the Messines offensive?

Carbery estimated that there were 3633 casualties at Messines between 7 and 13 June 1917, including 473 killed, 2726 wounded and 434 missing (he went beyond the NZEF’s departure from the lines on 9/10 June in order to include late casualty reports). [40] Many of the missing would later be counted among the dead.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission database lists the deaths of 727 New Zealand service personnel in Belgium between those dates, and 110 in France between 8 June – when wounded men were first evacuated there – and 13 June. This total of 837 will include a few men who died of illness and from injuries unrelated to the Messines offensive. The Messines data awaits in-depth analysis and refinement.

How many New Zealanders died during the Third Battle of Ypres (Broodseinde and Passchendaele)?

Carbery quotes a total casualty number of 6078 for October 1917 (the month of the Broodseinde and Passchendaele offensives during the Third Battle of Ypres), during which 1536 men were killed or died of wounds, 233 were reported missing and 4309 were wounded. [41] Andrew Macdonald extends the end date to 14 November to include late-reported casualties and puts the total at 8832, of whom 1796 died. His death figure is based on the number of New Zealand soldiers who died in Belgium during October 1917, according to the Commonwealth War Graves database. [42] This total will include some men who died of illness and injury unrelated to the Passchendaele offensive, while others injured at Passchendaele will have died in hospital in France. The fighting at Passchendaele made 12 October New Zealand’s worst day in any overseas war, with around 843 dead. [43]

How many New Zealanders died in each theatre of war?

The Roll of honour (1924) assigns the 16,697 deaths on active service between August 1914 and November 1918 to four theatres of war plus ‘United Kingdom and other places and at sea’. Gallipoli claimed 2721 lives (16.3%), while 12,483 (74.8%) died in France and Belgium, 381 (2.3%) in Palestine, 259 (1.6%) in Egypt and 853 (5.1%) in the United Kingdom and other places.

How many NZEF service personnel were executed?

Twenty-eight New Zealand soldiers were sentenced to death by the NZEF, and five were executed. [44]

How many New Zealanders died while serving in other British Empire and Allied forces?

As noted above, New Zealanders serving in other British Empire and Allied forces should be counted separately from the NZEF on the rare occasions when figures are available.

The only New Zealanders serving in imperial military forces who are now counted in the New Zealand roll of honour at the National War Memorial are 20 men who died while serving in the ‘New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy’. This unit was created shortly before the war as an administrative division of the Royal Navy’s China Station that would oversee Royal Navy activity around the New Zealand coast. These names are of men who served on HMS Philomel and Torch, naval vessels funded by the New Zealand government but under the control of the Royal Navy. They are not included in the published 1924 Roll of honour, which lists only men who served in the NZEF, but were added to the National War Memorial roll of honour in 1963–4, apparently as a way to retrospectively insert a New Zealand naval presence into the First World War roll. The CWGC database lists these men as members of a number of different – and mostly non-existent – naval forces. This probably reflects the relatively obscure administrative status of the ‘New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy’ within the Admiralty itself, never mind for the public at large, even at the time.

Researcher Errol W. Martyn has traced the history of New Zealanders who served in the various imperial and dominion air forces during the First World War. Martyn records that ‘over 70’ such New Zealand personnel lost their lives between 1915 and 1918 (Martyn, For your tomorrow: volume 1, 1915–1942, p. 37).

How many NZEF personnel were wounded?

As noted above, the Defence Department’s ‘casualty’ lists provide periodic tallies of those treated for wounds, illness and injury during the war, counting all those removed from the front line for medical treatment (though not necessarily for a long period of time). Total figures for ‘wounded men’, therefore, need to be treated with caution, because they count the number of times a person was admitted to hospital for any reason rather than the number of ‘wounded men’ per se.

Provision and maintenance lists 41,262 ‘wounded’ in its casualty statistics for August 1914 to November 1918; the department increased this figure to 41,317 in January 1920. [45] For the reasons described above, these figures, in aggregate form, provide no meaningful information about the number or severity of war-related injuries or illnesses sustained by New Zealanders. Figures for ‘wounded’ men are most meaningful in the context of specific campaigns and offensives, where they demonstrate the impact of those phases of combat on the forces involved.

The broader question of how many New Zealand soldiers were incapacitated by war-related illness or injury is therefore difficult to calculate with certainty. Between January 1915 and November 1918 the NZEF sent back to New Zealand 25,570 men, of whom 1555 subsequently returned to active service, leaving a net total of 24,015. A small proportion of these men had returned on long-service leave, but most were suffering from various medical conditions. This is probably a useful indication of how many men were incapacitated – to a greater or lesser degree – by injuries or illness sustained on military service, though more incapacitated men returned to New Zealand during the period of demobilisation after November 1918. [46]

How many New Zealanders were taken prisoner?

Provision and maintenance records that 356 New Zealand service personnel were taken prisoner, though this figure appears to count only those who survived to return to New Zealand. [47] The Defence Department increased the number to 498 in January 1920, presumably by adding those who had died in enemy custody. [48] Studholme counted 501 prisoners reported to June 1919, whether alive or dead. 25 of them were taken on Gallipoli, 12 in ‘Egypt’ (actually during operations in the Sinai Peninsula, Palestine and the region that became known as Transjordan) and 464 in France and Belgium. [49]

Frequently published figures, and what they mean

Personnel totals

7036 | The number of men who enlisted for Home Service in New Zealand in 1917 and 1918. They served in a variety of civilian roles in the training camps, coastal forts, Defence offices and elsewhere. |

9924 | The number of men in training camps in New Zealand at the time of the Armistice |

98,950 | The revised Defence Department figure for NZEF personnel despatched from New Zealand between 1914 and 1918, and considered to have been ‘on active service’. |

99,260 | The Defence Department’s Provision and maintenance figure for total NZEF personnel despatched from New Zealand between 1914 and 1918, and considered to have been ‘on active service’ – superseded in 1920 by a revised figure, 98,950. |

100,444 | Provision and maintenance figure for all NZEF personnel despatched from New Zealand between 1914 and 1918 (99,260), plus 1184 ‘miscellaneous’ personnel mainly shipped from New Zealand to Britain to join imperial units, who should properly be counted as part of those units rather than the NZEF. |

110,368 | Provision and maintenance figure for all NZEF personnel despatched from New Zealand between 1914 and 1918 (99,260), plus ‘miscellaneous’ personnel mainly shipped from New Zealand to Britain to join imperial units (1184), plus the troops in New Zealand training camps at the time of the Armistice (9924). |

117,175 | Provision and maintenance figure for total men called up and sent into camp (‘mobilised’) between 1914 and 1918, including men who died in camp or were discharged before the end of training. Provision and maintenance does not explain how this figure relates to its figures of 99,260, 100,444 or 110,368. |

124,211 | Provision and maintenance figure for total men called up and sent into camp between 1914 and 1918 (117,175, including men who died in camp or were discharged for any reason before the end of training), plus men involved in home service (7036). Provision and maintenance disaggregates this into 91,941 volunteers and 32,270 conscripts, without explaining where the Home Service men fit in. This figure is sometimes cited as the number of people ‘mobilised’, a misleading description. A significant proportion of this group never saw active service. |

128,525 | The Defence Department figure from January 1920 submitted to the British publication Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914–1920 (p. 771). This includes the 124,211 described above, plus 944 men sent from New Zealand to join imperial units and 3370 who were ‘known to have left New Zealand to join British and Imperial forces.’ This is the least defensible of all the department’s figures. |

Casualty totals

16,302 | Provision and maintenance figure for NZEF personnel who died between 5 August 1914 and 12 November 1918 (excluding those who died in camp in New Zealand) – superseded by the January 1920 figure, 16,697. |

16,697 | The Defence Department’s revised 1920 figure for NZEF personnel who died between 5 August 1914 and 12 November 1918 (excluding those who died in camp in New Zealand). |

18,058 | The current official First World War New Zealand roll of honour figure, comprising 18,052 personnel who died during the war and up to 31 August 1921, both overseas and at home, and six individuals added retrospectively. |

18,166 | The 1924 Roll of honour figure, which includes those killed in action before 12 November 1918, NZEF personnel who died between that date and 31 December 1923, discharged NZEF personnel who died up to 31 December 1923, and recruits who died while training in New Zealand between 1914 and 1918. |

18,500 | An oft-quoted figure for total New Zealand deaths, probably first published in A.H. McLintock’s Encyclopaedia of New Zealand (1966). No statistical foundation can be traced for this figure, but it may be an attempt to add deaths in other forces to the NZEF figure. |

58,004 | The Provision and maintenance total of the monthly tallies of people killed (16,302), ‘wounded’ (41,262), missing (84) and taken prisoner (356) between August 1914 and November 1918, minus those counted in error and subsequently accounted for. Individuals appear multiple times in the list, which should be read as the total incidence of death, hospitalisation, going missing, and being taken prisoner rather than as a total of individual people. Superseded by a figure of 58,014 in January 1920. |

58,014 | The Defence Department’s 1920 revision of the Provision and maintenance casualty figure of 58,004. |

Attached documents

1. Provision and Maintenance

Title: New Zealand Expeditionary Force: its provision and maintenance (pdf, 20 mbs)

Published in February 1919, Provision and maintenance is the most detailed statistical overview of the military side of New Zealand’s First World War experience which has ever been published. It provides a snapshot of the Defence Department’s knowledge at the end of the war, although some of the figures would be revised over the next few years.

This copy was held at the Defence Department’s head office, and the handwritten annotations reflect the process of amendment which followed its publication.

In 1922 the British War Office published a similar book covering the whole British Empire, Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914–1920, which can be downloaded here: https://archive.org/details/statisticsofmili00grea.

Provision and maintenance graphs (not in main pdf above)

- NZEF: dates of training camps, dates and strengths of mobilisations and embarkations, periods of training, and numbers in camp at any date

- NZEF: establishment of New Zealand Division and New Zealand Mounted Rifles, strengths of reinforcement drafts, and percentage rate of reinforcement

- NZEF: percentage of the total population and of the male population of military age mobilized and embarked

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8666 AD37/23/33

2. Roll of Honour

Title: The Great War, 1914–1918. New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Roll of honour (1924) (pdf, 114 mbs)

The official New Zealand Roll of honour was published in 1924, once the final casualty lists had been compiled and the Defence Department records updated. Copies were supplied to foreign governments and distributed to New Zealand politicians and military figures, but most of the print run of 1000 was offered for sale to the public. The Roll of honour remains the foundation of our knowledge of New Zealand’s war dead, though individuals can now be looked up on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database http://www.cwgc.org/ and Auckland Museum’s Cenotaph database http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/online-cenotaph.

Roll of honour graphs

3. Studholme

Title: Record of personal services during the war (1928) by John Studholme (pdf, 131mbs)

Lieutenant-Colonel John Studholme compiled his Record of personal services in the years following the war, as a companion volume to the four official war histories published by the government from 1919. He described the book as ‘unofficial, but based on official records’, but its endorsement by the Defence Department and publication by the Government Printer suggests it was official in all but name. The bulk of the book documents the careers of individual officers and the honours awarded to New Zealand personnel, but it also includes much useful information about how the NZEF operated.

John Studholme (1863–1934) was a landowner who commanded the Ashburton and South Canterbury Mounted Rifles before the war. He was promoted to major and temporary officer commanding the Canterbury Mounted Rifles at Gallipoli in May 1915, and served as Assistant Adjutant-General to the NZEF from 1917 until 1919.

Studholme graph (not in main pdf above)

4. Return of troop transports

Title: List of New Zealand troopships, 1914–19 (pdf, 17mbs)

This list of troop transports, along with the number of men and horses aboard and the dates of departure and disembarkation, appeared in a report prepared by the Defence Department’s Director of Movements and Quartering in August 1919. The most detailed known list, it records troopships carrying men of the NZEF to Egypt and Western Europe, hospital ships, and vessels returning men to New Zealand. It does not include troop movements to or from Samoa after the Advance Party. These lists complement the official embarkation lists, on which the names of every individual aboard each ship appear. A selection of troopship magazines can be read here: http://muse.aucklandmuseum.com/databases/LibraryCatalogue/SearchResults.aspx?Page=1&c_keyword_search=troopship+magazine&c_subject_search=world+war+1914-1918.

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8638 AD1/1006 51/745 pt 1

5. Recruiting 1916–18

Title: Report on conscription, 1916–18 (pdf, 38mbs)

Director of Recruiting D. Cossgrove wrote this assessment of recruiting under conscription in March 1919. It includes a detailed overview of how the scheme operated, recruiting circulars explaining the day-to-day workings of the system, and some useful statistics.

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8638 AD1/712 9/169 pt 2

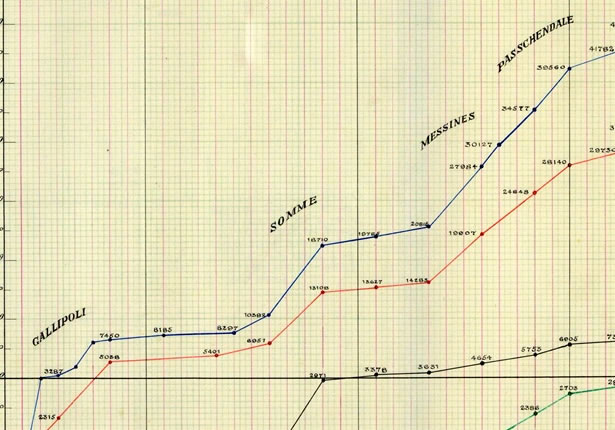

6. Casualties graph

Title: Casualties, 1915–19 (graph)

Drawn by the Defence Department’s Base Records Branch in 1919.

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8638 AD1/1006 51/745 pt 2

7. Return showing soldiers returned to NZ (MS)

Title: Graph of soldiers returning to New Zealand, 1916–19

Drawn by the Defence Department’s Base Records Branch in 1919.

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8638 AD1/1006 51/745 pt 2

8. Monthly returns of disposal of soldiers disembarked (MS)

Title: Monthly returns of soldiers disembarking in New Zealand, 1916–19 (graph)

Drawn by the Defence Department’s Base Records Branch in 1919.

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8638 AD1/1006 51/745 pt 2

9. Fraser report

Malcolm Fraser, ‘War work of the Census and Statistics Office’, November 1919

Government Statistician Malcolm Fraser compiled this potted history of the wartime conscription process from the perspective of those responsible for administering it. It provides many useful clues to how the process was undertaken, and is a useful counterpoint to the Defence Department perspective provided by the Cossgrove report. It includes a table of figures outlining the number of men called up in each ballot, though it omits the men called up in the 23rd ballot in October 1918.

Reference:

IA1 box 1652 29/125, Archives New Zealand

Further reading

- Paul Baker, King and country call: New Zealanders, conscription and the Great War, Auckland, 1988

- Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey, ‘New Zealanders in the AIF: an introduction to the AIF Database Project’, in J. Crawford and I. McGibbon (eds), New Zealand’s Great War: New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, pp. 394–405

- The Great War, 1914-1918. New Zealand Expeditionary Force. Roll of Honour, Wellington, 1924

- Glyn Harper, Dark journey, Auckland, 2007

- David Littlewood, ‘“Willing and Eager to Go in their Turn”? Appeals for Exemption from Military Service in New Zealand and Great Britain, 1916–1918’, War and Society, vol. 21, no. 3, 2014, pp. 338–54

- Andrew Macdonald, On my way to the Somme: New Zealanders and the bloody offensive of 1916, Auckland, 2005

- Andrew Macdonald, Passchendaele: the anatomy of a tragedy, Auckland, 2013

- Ian McGibbon (ed.), The Oxford companion to New Zealand military history, Auckland, 2000

- NZEF casualty lists, Wellington, 1915–19

- NZEF embarkation rolls, Wellington, 1917–19

- Christopher Pugsley, Gallipoli: the New Zealand story, revised edn, Auckland, 2014

- Christopher Pugsley, On the fringe of Hell: New Zealanders and military discipline in the First World War, Auckland, 1991

- Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914–1920, London, 1922

- Richard Stowers, Bloody Gallipoli, Auckland, 2005

- John Studholme, Record of personal services during the War of officers, nurses, and first-class warrant officers; and other facts relating to the NZEF, Wellington, 1928

- War, 1914–1918. New Zealand Expeditionary Force: its provision and maintenance, Wellington, 1919

Notes

[1] New Zealand official year-book, 1919, pp. 255–6.

[5] H. Turner, Under-Secretary of Defence, to J. Hand, 31 May 1935, AD1 894 39/235 pt 2, Archives NZ.

[6] D. Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916–18’, appendices 3(4) and 12, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2, Archives NZ.

[7]‘Roll of Honour, Men born in Scotland who served with NZ Expeditionary Force’, in AD1 1254 276/1/2, Archives NZ.

[8] Provision and maintenance, pp. 43, 45–7.

[9] Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey, ‘New Zealanders in the AIF: an introduction to the AIF Database Project’, in J. Crawford and I. McGibbon (eds), New Zealand’s Great War: New Zealand, the Allies, and the First World War, p.401

[10] Provision and maintenance, table X, records the ‘number of troops provided by New Zealand from Outbreak of War to 12th November, 1918’ – including troops who never reached the front. These are distinguished from men ‘in training in New Zealand on 12th November 1918’ (table XVIII).

[11] D. Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916–18’, appendices 2 and 3, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2, Archives NZ.

[14] D. Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916–18’, appendices 4, 5, 6(1), and 9, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2, Archives NZ; Provision and maintenance, p. 47.

[17] D. Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916–18’, appendix 9, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2, Archives NZ; Baker, King and country call, p. 220.

[20] Military Service Act 1916, s. 14(c); Home Service regulations, New Zealand Gazette, 21 June 1917, pp. 2445–6; 9 July 1917, p. 2764; 29 August 1918, p. 3082; evidence of Major C.E. Andrews to the Defence Expenditure Commission, 15 February 1918, pp. 106–10, LE1 680 1918/14 pt 1, Archives NZ

[22] Provision and maintenance, Graph 1; for population total see Government Statistician to Chief of the General Staff, 27 July 1917, AD1 893 39/235 pt 1, Archives NZ. This total is markedly lower than the official population estimate for 31 December 1914, 1,158,436, published in the 1915 Official year-book (p. 95), and the 1916 census figure of 1,142,115 (including 42,666 soldiers serving overseas) (Census, 1916, pp. 12, 15).

[23] Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–20, pp. 62–3.

[25a] Defaulters list (NZHistory).

[25b] Paul Baker, ‘New Zealanders, the Great War, and Conscription’, Phd thesis, University Auckland, 1986, p.386.

[26] ‘Return of cases dealt with under the Military Service Act to 31 March 1919’, AD1 1039 64/28, Archives NZ.

[27] Defaulters list (NZHistory).

[31] Roll of honour, p. xviii; Studholme, Record of personal services during the War, p. 383.

[35] Roll of honour, p. xviii. Chris Pugsley’s history of the campaign adopts these figures (Gallipoli: the New Zealand story, revised edn, Auckland, 2014, p. 366).

[36] Richard Stowers, Bloody Gallipoli, Auckland, 2005, p. 275. See also David Green, ‘How many New Zealanders served on Gallipoli?’, 2013 (WW100)

[40] A.D. Carbery to G.O.C. Administration, 11 March 1921, AD1 894 39/235 pt 2, Archives NZ; repeated in his The New Zealand medical service in the Great War 1914–1918, p. 315.

[41] A.D. Carbery to G.O.C. Administration, 11 March 1921, AD1 894 39/235 pt 2, Archives NZ; repeated in his The New Zealand medical service in the Great War 1914–1918, p. 356.

[43] Andrew Macdonald (Passchendaele: the anatomy of a tragedy, p. 243) puts the precise figure at 845, while Glyn Harper (Dark Journey, p. 90) has 846. More recently, Ian McGibbon has made the case for it being 843.

[45] Provision and maintenance, p. 50; Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914–20, p. 771; this figure was subsequently republished in Studholme, Record of personal services during the War, p. 383.

[49] Studholme, Record of personal services during the War, p. 384. Historian David Filer put the figure at 506, adding five to the total Gallipoli/Egypt deaths counted by Studholme, in his entry on prisoners of war in Ian McGibbon (ed.), The Oxford companion to New Zealand military history, Auckland, 2000, p. 430.

Author: Tim Shoebridge, 2015