Darwin’s visit to the Bay of Islands on HMS Beagle was brief and unspectacular from his point of view. The Beagle’s captain, Robert FitzRoy, would later serve as the second governor of New Zealand.

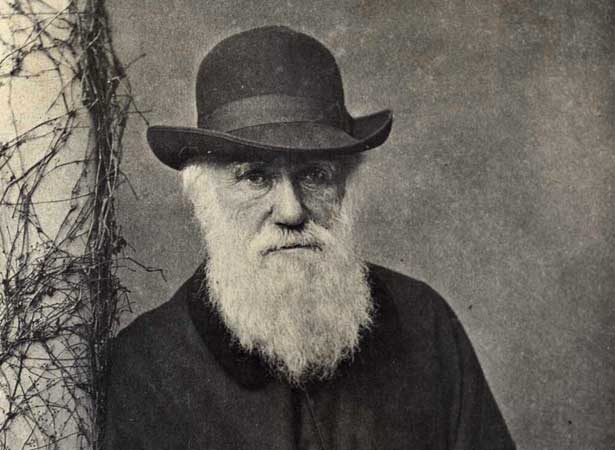

New Zealand was a short stopover on FitzRoy’s five-year expedition, the main aims of which were to chart the southern coast of South America and run a chain of chronometric readings (used to determine precise longitudes) around the globe. The trip was an ideal opportunity for a scientist to collect specimens from around the world, and after some enquiries Charles Darwin, a promising young naturalist and recent Cambridge graduate, was recommended for the job. The Beagle set sail in December 1831 and arrived in the Bay of Islands four years later.

The story of Darwin’s nine-day visit to New Zealand is told in Lydia Monin’s From the writer’s notebook (Reed, 2006). On 21 December 1835 the Beagle anchored in a harbour flanked by the grogshops and brothels of Kororāreka on one side and the Church Missionary Society (CMS) settlement at Paihia on the other. After a few uncomfortable days visiting these settlements, Darwin and FitzRoy were invited by CMS missionary William Williams to visit the Waimate mission station, 21 km inland from Paihia.

The journey was made on foot and by boat, guided by a Māori chief whose services were paid for by James Busby, the British Resident. At Waimate, FitzRoy and Darwin were pleased to find an oasis of English civilisation, complete with cups of tea and cricket on the lawn. Darwin approved of the Māori labourers and maids – the latter’s ‘clean, tidy and healthy appearance, like that of the dairy-maids of England, formed a wonderful contrast with the women of the filthy hovels in Kororadika [Kororāreka]’.

During his stay in New Zealand Darwin collected insects, shells, fish, rocks and a gecko. His detailed observations were carefully recorded in his journal of the Beagle expedition, which was published to much acclaim in 1839. He later wrote that the voyage had been ‘by far the most important event in my life, and has determined my whole career.’ But he did not remember New Zealand fondly. The country was unattractive; its English inhabitants, apart from the missionaries at Waimate, were ‘the very refuse of society’; Māori lacked the ‘charming simplicity which is found in Tahiti’.

Read more on NZHistory

External links

How to cite this page

'Charles Darwin leaves New Zealand after nine-day visit', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/charles-darwin-leaves-nz-noting-that-it-is-not-a-pleasant-place, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 5-Oct-2021