Flag

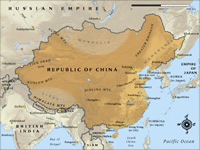

1917 Map

Click on map for more detail

General facts

- Population: 456 million (1917)

- Capital: Peking/Beijing (1917 population 811,000)

Government

- Head of State:

- President Li Yuanhong (6 June 1916 – 1 July 1917)

- President Feng Guozhang (6 August 1917 – 10 October 1918)

- President Xu Shichang (10 October 1918 – 2 June 1922)

- Head of Government:

- Premier Duan Qirui (26 June 1916 – 23 May 1917)

- Premier Li Jingxi (28 May 1917 – 1 July 1917)

- Premier Duan Qirui (14 July 1917 – 22 November 1917)

- Premier Wang Shizhen 30 November 1917 – 20 February 1918)

- Premier Qian Nengxun (20 February 1918 – 23 March 1918)

- Premier Duan Qirui (23 March 1918 – 10 October 1918)

- Premier Qian Nengxun (10 October 1918 – 13 June 1919)

- Premier Gong Xinzhan (13 June 1919 – 24 September 1919)

Although the government in Beijing enjoyed universal international recognition as the legitimate government of the Chinese Republic during this period, the country was very politically unstable and the hopes unleashed by the 1911 revolution that ended Qing imperial rule were beginning to rapidly sour. An attempt by the republic’s second president, Yuan Shikai, to make himself emperor had ended only with his death in June 1916. The restoration of republican government was threatened a year later when Zhang Xun – a pro-monarchist general – and his army were brought in to the capital to bolster President Li Yuanhong’s rule, only to see the general overthrow the president, dissolve parliament and announce the restoration of the Qing emperor on 1 July 1917. This attempted coup was put down a few weeks later, but the situation remained unsettled.

Meanwhile, republican leader and revolutionary Sun Yat-sen and his supporters set up a breakaway ‘Southern Government’ in Canton (Guangdong) in August 1917, ostensibly to better protect the republic’s provisional constitution. From then until the early 1920s the two governments, north and south, alternated between efforts at reconciliation and sporadic attempts to quash each other by force. This confrontation helped to exacerbate the chaotic social conditions that led to the rise of regional warlords and their private armies that would plague China in the 1920s and 1930s.

Participation in the War

- Entered the war: 14 August 1917 (China declared war on Germany)

- Ceased hostilities: 11 November 1918 (armistice with Germany)

- Ended belligerent status: 20 May 1921 (peace treaty signed with Germany)

The Chinese delegation to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles in protest at the decision of the Principal Powers (France, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States) to recognise Japan’s claim over the former German colonial territory of Qingdao and the surrounding province of Shandong instead of returning the area to Chinese rule. The Chinese government subsequently negotiated a separate peace treaty with Germany.

Chinese Labourers in French and British Service on the Western Front

French Chinese Labour Corps

- Recruitment began: July 1916

- Recruitment ended: February 1918

- Total recruited and sent to the Western Front: 45,000

In May 1916 the French and Chinese governments secretly agreed to allow the recruitment of up to 50,000 Chinese labourers to serve behind the lines in France. To avoid accusations that this violated China’s official position of neutrality, the labourers were recruited by private Chinese front companies and then contracted out to French front companies, ostensibly for private civilian work in France. The first Chinese labourers contracted under this scheme arrived in France in August 1916. On arrival they came under the control of the French Ministry of War and were organised and treated as labour units of the French Colonial Army.

On 24 February 1917 the French transport ship SS Athos was torpedoed by a German U-boat in the Mediterranean on its way from China to France. A total of 543 Chinese labourers on board died in the sinking. On 14 March the Chinese government broke off diplomatic relations with Germany in protest.

British Chinese Labour Corps

- Recruitment began: November 1916

- Recruitment ended: April 1918

- Total recruited: 106,000

- Total sent to the Western Front: 100,000

- Total sent to Mesopotamia and Egypt: 6000

Following the French lead, the British decided to establish their own Chinese labour recruitment programme in August 1916. Unlike the French, they used private recruitment agents in China who were contracted directly to the British War Office. The recruitment agents simply directed potential recruits to the British territory of Wei-hai-wei in Shandong Province, where they were given contracts by British Foreign Office staff and placed under the administrative control of the War Office. After some teething problems this scheme was in full operation by the end of 1916. The first contingent of 1000 recruits embarked from Wei-hai-wei for England on 18 January 1917 and arrived in Plymouth on 11 April. The British Chinese Labour Corps was organised as a labour unit of the British Army and the recruits were subject to British military law.

Role of Chinese labourers on the Western Front

Chinese labourers worked on the docks and in railway yards and supply depots behind the lines, loading and unloading supplies, building and repairing roads, railways and other facilities. They frequently came within range of enemy artillery while carrying out their most dangerous tasks, building support trenches, roads and other structures in the rear areas of the front line. Some were killed or wounded by shellfire while carrying out these tasks.

End of the French and British Chinese labour programmes 1918

Following the entry of the United States into the war in April 1917 the US Army expanded rapidly. The need to transport this vast American force across the Atlantic Ocean to France put increasing pressure on the already stretched capacity of Allied shipping to meet all the demands being made upon it. The French, and then the British, both decided to halt their Chinese labour recruitment programmes to free up transport ships to carry more American troops from the United States to France. The French shut down their Chinese recruitment network on 10 February 1918 and the British closed theirs on 18 April. The British estimated that by doing so they would enable an extra 10,000 American soldiers to cross the Atlantic each month.

Military Forces

Army

- Strength 1918: 850,000 (‘National Army’ – controlled by government in Beijing)

This does not include the forces raised by the breakaway government in Canton or other regional Chinese garrisons or armies that refused to acknowledge the authority of Beijing.

Attempts to send Chinese troops to the Western Front

In the months leading up to China’s declaration of war on Germany, the Beijing government conveyed to the French and British its willingness to send up to 100,000 men to fight on the Western Front – but only if they were equipped and paid for by the other Allied powers. This offer was politely rejected by both Paris and London. Not only was this demand impractical, the Japanese government objected strenuously to the appearance of any Chinese troops in the European theatre of war.

In September 1917 the Chinese put forward a much more realistic and modest proposal to send an expeditionary force of 40,000 men to the Western Front. This proposal won strong support from the French government. The Chinese soldiers would be equipped by the French and serve in thousand-man battalions under French operational command. The Americans promised financial support. A Chinese general, Tang Zaili, was sent to France in November 1917 to liaise with the French in preparation for the arrival of the first Chinese battalions.

But negotiations with the British over the provision of transport ships bogged down. Meanwhile, the American offer of financial support faded as the months dragged on and the United States’ own war effort ramped up. Finally Japan, which had at first reluctantly agreed with the proposal, took advantage of the loss of momentum and reiterated its opposition to the use of Chinese troops in Europe. Faced with increasing indifference or outright obstruction from all the other major Allies, the French gave up. To the Chinese government’s frustration and the French government’s embarrassment, in April 1918 the French informed the Chinese that the 40,000 Chinese soldiers who had been ready and waiting in China since November 1917 would no longer be required.

Navy

- Peacetime strength 1917: 6000

Fleet (1917)

- Cruisers: 4

- Light cruisers: 3

- Destroyers: 4

In July 1917 the officers and crew of three Chinese warships abandoned their station at Shanghai and fled in their ships to the south, where they defected to the ‘Southern Government’ in Canton. This effective break-up of the Chinese Navy prevented any possible deployment of its ships in support of the Allied war effort.

Casualties

Chinese labourers in French and British service

- Dead (all causes): 5000

This figure includes 783 men lost at sea due to U-boat attacks on transport ships carrying them from China to France or the United Kingdom.

Sources

- Sidney David Gamble, Peking: A Social Survey, George H. Doran, New York, 1921

- William C. Kirby, Germany and Republican China, Stanford University Press, Stanford CT, 1984

- Michael Summerskill, China on the Western Front: Britain’s Workforce in the First World War, M. Summerskill, London, c. 1982

- Guoqi Xu, China and the Great War: China’s Pursuit of a New National Identity and Internationalization, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005