Although a number of New Zealand’s First World War aviators saw action at Gallipoli and in the Middle East, the vast majority flew with the British air services over the Western Front. They became part of the remarkable story of how the aeroplane, a new and primitive weapon in 1914, developed into a key element of warfare by the end of hostilities.

The vast and rapid expansion of British air power during the war can be observed through its growth of personnel from just over 2000 officers and men of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) in August 1914 to almost 300,000 by the Armistice in November 1918. At war’s end its aeroplane strength numbered over 22,000 – a far cry from the less than 200 ill-suited machines of mostly marginal performance that it started out with.

The Air War: 1914

The Western Front in 1914 began as a war of movement, with German forces sweeping into Belgium then France. Aircraft were used initially mostly in the reconnaissance role that had been envisaged for them pre-war – finding and identifying enemy and friendly forces.

Pilot training

Until the latter half of the war British flying training was of a poor standard that resulted in many unnecessary deaths by accident, or in combat when pilots were despatched to the Western Front often with only a score or two of hours logged in the air. Of the 7000 aircrew who were killed or died of wounds or injuries, a staggering 3000 fell victim to flying accidents. As training standards gradually improved, aircrew gained better skills and had fewer accidents. Innovative methods of flying instruction that were later developed world-wide were developed by Robert Smith-Barry at the School of Special Flying at Gosport, Hampshire. By the end of war, the Royal Air Force had established numerous specialist training centres, such as the Schools of Aerial Fighting.

The RFC flew four squadrons across the English Channel in August 1914, with their supporting ground crew, equipment and vehicles travelling by sea. They operated as a group under the command of Sir David Henderson. One of the pilots was Hugh Reilly of Hawke's Bay, who had learned to fly in 1912 and would soon be in the thick of the action. The first operation, on 19 August, was a reconnaissance by two aircraft with the goal of identifying German and Belgian forces. Neither was successful in its mission, illustrating how difficult such work would be under operational conditions. An additional danger was that troops of all sides fired on the unmarked aircraft. Early markings such as the Union Flag looked very like the German Maltese Cross from a distance, so British and French aircraft adopted the three-colour roundel instead.

On 22 August 1914, the RFC lost its first aircraft and crew in action during a series of reconnaissance flights to locate German forces. Senior army officers took some convincing about aerial reports indicating that the Germans were converging on the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Following the Battle of Mons and the subsequent British retreat, RFC aircraft frequently operated from simple temporary landing grounds, which changed daily as the British Army fell back. Aircraft reconnaissance proved highly useful in early September, when a gap formed between the German armies advancing on the Marne and a counter-attack forced them to retreat.

Once the Germans had been stopped on the Marne and static trench warfare developed, the role of aircraft changed. The RFC was dispersed along the ever-lengthening front lines that were developing in Flanders. Knowledge of the German trench systems and what lay behind them was vital. Initially, observers (sitting in the second seat of the aeroplane) made sketches and took notes, but as the network of trenches developed, recording such complex positions this way became impossible. Aerial photography gradually took over as the recording method, using techniques experimented with before the war.

In late 1914, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) on the Continent was based at Dunkirk, from where it defended the Belgian port city of Antwerp and launched attacks on German troops converging on the Channel coast. They also used armoured cars in this period of open warfare. On 9 October, the RNAS carried out one of the first strategic bombing raids in history, attacking the German airship sheds at Dusseldorf and destroying one Zeppelin. Further attacks from bases in France also targeted the Zeppelin factory at Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance and the naval base at Cuxhaven in northern Germany.

In the few months of fighting in 1914, the numbers and roles of aircraft had increased amongst all the combatants. In addition to operations in France and Belgium, it became clear that the RFC would need more aircraft and personnel to meet the British Army’s increasing need for aerial support. A Directorate of Training was set up to provide the personnel required. Despite shortages of engines (the British being heavily reliant on supplies from the French), production by the Royal Aircraft Factory and private manufacturers was increased. By the end of 1914, the RFC had twice as many personnel as it had had at the start of the war.

The Air War: 1915

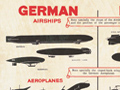

Prior to the First World War, Britons greatly feared the threat posed by German airships or ‘Zeppelins’. Ironically, the first German aerial attacks on Britain, in December 1914, came from seaplanes based on the Belgian coast. German airship attacks on Britain commenced on the night of 19 January 1915, when Zeppelins bombed targets on the Humber Estuary and Thames rivers, killing four people and injuring 16. On the night of 31 May, airships attacked London for the first time. Sporadic airship raids followed, some as far north as Tyneside. Aerial defences were initially poor, with a lack of guns, searchlights or suitable aircraft to counter the high-flying airships. While the visits of these so-called ‘baby killers’ caused widespread public alarm, German airships caused little serious damage to British infrastructure.

With the Western Front now locked in stalemate, both sides began to expand their use of aircraft. When the British and French went on the offensive in early 1915, the needs of the army became paramount. It soon became clear that artillery ruled the battlefield. Enemy installations that were dug in or hidden offered few clear targets. To counter this problem, aircraft began searching for the gun batteries on artillery observation missions. To improve communication, RFC wireless operators joined artillery batteries to relay information between the aircraft and gunners. In 1915, the British adopted a sophisticated system in which the target was visualised as the face of a clock. The aeroplane observer described the fall of shells in relation to this ‘clock-code’ and sent the gunners corrections by wireless telegraphy. This was a major step forward in improving the accuracy of artillery fire.

Anti-aircraft artillery fire was a constant threat to an aircraft over the lines. Although generally inaccurate, ‘Archie’ could fatally damage an aircraft with a near miss. Lower down, the fabric-covered aircraft, which offered little protection for the crews, were also vulnerable to rifle and machine-gun fire. As the war progressed, anti-aircraft weapons improved in both size and accuracy.

Aircraft also bombed ground targets, and it was on one of these missions that Lieutenant William Rhodes-Moorhouse became the first airman to win the Victoria Cross (VC). On 26 April 1915, Rhodes-Moorhouse, who was part Māori, suffered severe wounds during an attack on a rail junction at Courtrai. Despite his injuries, he guided his aircraft back to base and refused medical attention until he had filed his report. He died shortly afterwards.

By 1915, the RFC was growing and developing rapidly. Some units became corps squadrons which operated in direct support of the British Army; others merged into wings. The first British unit to be equipped with a single type of aircraft was No. 11 Squadron, which arrived in France provided with the Vickers FB.5 'Gunbus' in July 1915, thus simplifying equipment stores, servicing, and planning of operations.

By the close of 1915, aircraft were beginning to play a key role in the planning of battles and were influencing the nature of trench warfare. Their role would be refined further and increasingly integrated with that of the ground forces during the significant battles to come on the Western Front in 1916.

The Air War: 1916

During 1916, attacks by German airships on Britain increased in intensity. Initially, the RNAS and RFC were ill-equipped to counter the threat. Though a network of airfields was set up around London, night-flying was a relatively new and dangerous activity. Unless caught in a searchlight, it was extremely difficult to locate an airship in the dark and most aircraft struggled to even reach the high-flying enemy let alone shoot him down. Notwithstanding these challenges, three Zeppelins and a Schütte-Lanz airship were spectacularly shot down in flames over England by aircraft; not a single crew member survived. New Zealander Alfred de Bathe Brandon had two close but frustratingly unsuccessful solo encounters with Zeppelins in 1916, but only after they had been damaged by anti-aircraft fire (which finally led them to crash) and were unable to climb away.

On the Western Front, the RFC was still coping with the threat of the Fokker Eindecker fighter aircraft. A major turning point came in the spring of 1916 when No. 24 Squadron arrived in France, commanded by Major Lanoe Hawker VC, Britain’s first air ace. It was equipped solely with the Airco DH.2, a small pusher fighter (with the propeller mounted behind the engine) designed by Geoffrey de Havilland. Highly manoeuvrable and with a forward-firing fixed Lewis gun, the DH.2 was more than a match for the Eindekker and gradually the German threat was contained.

On 21 February 1916, the Germans opened the offensive at Verdun that was designed to bleed the French Army to death. The fighting in the air was no less severe, with the French countering the Fokker threat with new types of aircraft such as the Nieuport 11, which had a Lewis gun fitted to the top wing. The French held firm through months of bitter fighting on the ground and in the air.

Designed to relieve the pressure on the French at Verdun, the Battle of the Somme is symbolic of the senseless slaughter and failure of the First World War, with nearly 55,000 casualties on the first day of the offensive. However, the corresponding effort in the air was actually a success. During the first three months of the campaign, the RFC was able to gain aerial superiority over the battlefield. It continued to pioneer new roles and techniques, including ground attack and contact patrols; the latter involving flying low over the battlefield to identify the progress of the troops and then dropping a message back in British lines. RFC pilots also attacked railheads, camps and dumps to try to weaken German defences and disrupt the flow of reinforcements.

The German Imperial Air Service also changed its approach in the autumn of 1916. Instead of using fighters in small numbers, they formed larger Jagdstaffel (or Jasta) fighter squadrons under the command of men like Oswald Boelcke, who had developed the first set of tactics for fighter pilots. These developments went hand in hand with the introduction of new types of fighters, the Albatros and Halberstadt D. These were fast, rugged and carried two forward-firing machine guns. Thanks to sophisticated signalling systems these fighters could concentrate quickly on a selected Allied formation.

However, the Germans could not be everywhere at once and the RFC was able to perform successfully its key role of supporting the Somme ground campaign. Wellington-born Keith Caldwell, serving with No. 8 Squadron RFC, flew the stable but vulnerable BE.2c reconnaissance aircraft on vital missions during the battle.

The Air War: 1917

By 1917, the blueprint for aerial operations on the Western Front was firmly established. After the end of the Battle of the Somme in October 1916 there was little activity during the severe winter that followed. The German retreat to the defensive Hindenburg Line during February-March made continued aerial reconnaissance by the Allies vital.

By the time the Battle of Arras commenced in April 1917, the technological edge was firmly with the German Imperial Air Service. Whilst the Albatros series of fighters had been improved and refined, many British units were still flying vulnerable BE.2c and FE.2b reconnaissance aircraft. Fighters such as the now-obsolete DH.2 and Nieuport Scouts were little better. New German tactics and organisation increased the threat to Allied aviators. The Germans now grouped their Jastas into larger Jagdgeschwaders, beginning with JG.1 under their iconic leader Baron Manfred von Richthofen (the 'Red Baron'). During this period, later known as ‘Bloody April’, the British lost 316 pilots and crew killed or captured, four times the Germans’ losses. Three New Zealanders – John Cock, George Masters and Melville White – were amongst these casualties.

Despite these terrible losses, the RFC, supported by several fighter squadrons of the RNAS, continued their artillery spotting, army co-operation, bombing, and long-range reconnaissance missions. In mid-1917, they regained some parity with the introduction of improved aircraft such as the Royal Aircraft Factory SE.5a, Sopwith Camel, and the revised Bristol F.2b Fighter. For their part, the Germans introduced the distinctive Fokker Dr.1 Triplane and the upgraded Albatros DV.

In the later battles of 1917, particularly at Cambrai in November, both sides provided direct support to the soldiers on the ground through specific ground-attack roles. On the British side, this sometimes involved aircraft less suited to other duties, such as the disappointing Airco DH.5 fighter. The Germans meanwhile introduced the armour-protected Junkers J.1, Halberstadt CL.II and Hannoverana C.III for low-level operations.

Aircraft were now co-operating with Britain’s secret invention – the tank. Tanks were first used in September 1916 but proved too few and unreliable. By the time of Cambrai, they were very much part of the weapons systems of the British and French armies and aircraft began to work closely with them, as they had with the infantry on the Somme the previous year.

In May 1917, a more potent German aerial threat to British cities emerged. Heavy twin-engine ‘Gotha’ bombers attacked targets in Kent on 25 May from their base at Ostend on the Belgian coast. The attack killed 95 people and injured 195. Nineteen days later their first daylight raid on London killed 162 and injured 432, with a direct hit on a primary school. The badly coordinated air and ground defences were unable to reach the high-flying Gothas. Faced with a public outcry, the British government set up a committee headed by the South African leader, Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts, to investigate the organisation and purpose of military aviation. This was to have a direct impact on British military aviation in the following year.

The Gothas continued to attack by day and then, joined briefly by the Zeppelin fleet and a few four-, five- and six-engined R-planes (fittingly known as ‘Giant’), by night. Improvements in the coordination of defending guns, aircraft and searchlights, and the introduction of specialist units, saw five bombers lost and the others driven off in the last major raid, on the night of 19 May 1918. In the face of such opposition, the Gothas turned their attention to supporting the German Army on the Western Front.

The Air War: 1918

The year 1918 started very badly for the Allies, while in the East the Soviet government signed a treaty on 3 March with the Germans ending four years of war between the two powers that released the latter’s troops there for the Western Front. Eighteen days later the Germanys launched a massive offensive in the West that caught Allied forces on the ground and in the air by surprise. As German troops pushed forward, the Allies rapidly abandoned several airfields, evacuating equipment and personnel to new bases. Meanwhile the British flew desperate missions to try to disrupt the German advance. Often at low level, these were highly dangerous and resulted in the deaths of many experienced aircrew. With the enemy offensive halted in the mid-1918, the British Army and RAF went back onto the offensive, with the added confidence that American air units were now starting to arrive on the Western Front.

At the height of the desperate defensive fighting in France, the RFC and RNAS amalgamated to form a single Royal Air Force (RAF) on 1 April. The change was a direct consequence of Smuts’ report, which highlighted the duplication of effort and rivalry between the Admiralty and War Office in regards to Britain’s air defence. The new service adopted traditions from both the amalgamated units. At the same time the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) was created. Employing women in traditionally male roles freed up more men for service overseas. At least two New Zealand women served with the WRAF: dispatch rider Madeline Rankin and Harriet Simeon, who rose to the rank of Deputy Assistant Commandant by 1919.

Britain had endured airship and aeroplane attacks throughout the war, and the RAF finally began hitting back in 1918. Operating from bases in north-east France, a force of RAF bombers – Independent Force – began bombing industrial targets in western Germany. Whilst the resulting damage was not extensive, the activities of Independent Force helped the RAF develop aerial-bombing techniques and strategies.

After four long years of naval blockade and the attrition of intense combat, the Germans faced ultimate defeat despite the introduction of outstanding aircraft such as the Fokker D.VII fighter. Intense aerial battles took place above the battlefields at Amiens in August 1918 and throughout the subsequent ‘One Hundred Days’ offensive on the Western Front. Outnumbered, and facing fuel and equipment shortages, the German Imperial Air Service was on the back foot. With British, French and now American air forces ranged against them, German aerial resistance weakened.

Following the signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918, a large quantity of equipment fell into Allied hands and the victorious nations occupied German territory on the Rhine. The RAF contingent supporting the British Army of the Rhine included several New Zealanders.

In just four years, the aeroplane had been transformed from a fragile reconnaissance machine into a crucial part of a huge all-arms battle system. Only marginally capable of carrying out operations in 1914, by war’s end they were now of far more robust construction, some also being equipped with armour-plating. Aided by dramatic increases in engine power, typical bomb-carrying ability increased from a few score kilos to, for large bombers, several tons. Oxygen and heating apparatus for the crew were among some of the new technologies gradually being introduced. Air power had transformed the nature of warfare and influenced the way nations planned for future conflicts. An air force was now an essential component of a country’s armed forces. With experienced airmen returning from overseas, New Zealand was no exception. The New Zealand Permanent Air Force created in 1923 after some discussion and analysis was the precursor of the Royal New Zealand Air Force.