This essay written by Clare Simpson was first published in Women Together: a History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand in 1993.

The Atalanta Cycling Club, established in Christchurch on 18 August 1892, was the first all-women's cycling club in Australasia. Its aims were to unite female cyclists, providing them with both recreational and social opportunities. Although the earliest cycling club in New Zealand began in 1877, women were rarely seen cycling until the 1890s. The Canterbury Times in 1892 reported there were 4000 cyclists in Christchurch out of a population of 51,000, and boasted that:

everyone cycles—both sexes, all ages, all ranks. Ladies make calls thirty miles out. . . . There were lady cyclists in Christchurch when they were practically unknown in other parts of the world, and they cycled in knickerbockers, and tasted the freedom of the reform dress when their sisters elsewhere were merely talking of it in whispers. [1]

If women were allowed to belong to clubs at all, it was to 'ladies' branches' of male cycling clubs, where activities were strictly segregated. One topic women wished to discuss with each other was the matter of cycling dress—'rational dress' (bloomers or knickers) versus cycling skirts or divided skirts—which did not interest their male counterparts.

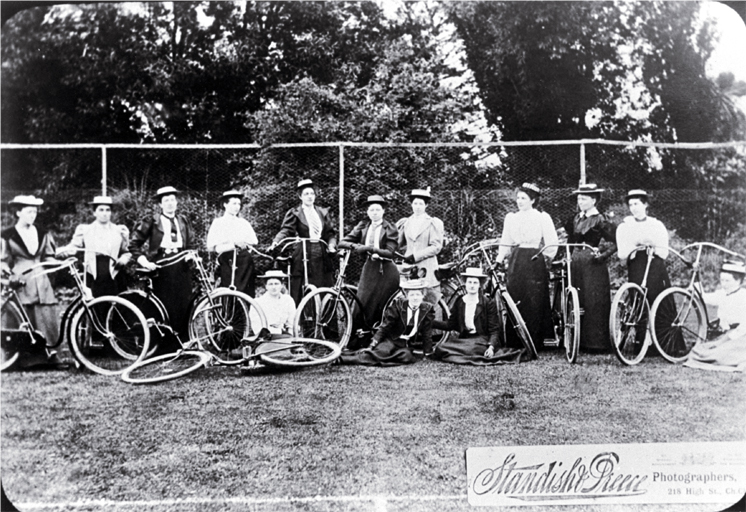

Christchurch City Libraries: photographer Standish & Precce, Photo CD 1, IMG0068.

Members of the Atalanta Ladies' Cycling Club, c1893. In accordance with the club’s rules on dress, none of the members are wearing ‘rational dress’ or even a divided skirt.

The motion to form the Atalanta Cycling Club was put by Alice Burn, a strong advocate for dress reform, who became the club's first secretary. Eighteen-year-old Blanche Lough was captain, Miss Keating sub-captain, and Miss A. E. Barker honorary treasurer. Members of the committee were ‘Mrs Shephard’, [2] Bertha Lough and Miss F. Adams. The (amended) rules of the men's Bicycle Touring Club were adopted, but the matter of club uniform was postponed until a later meeting, where it was decided to let women wear what they wished provided the club colours and emblem were worn. However, in September 1893, because the club had suffered bad publicity from the report that all the members were in favour of rational dress, it was unanimously agreed that none of the members be allowed to appear in that costume. The motion was rescinded a couple of years later when dress reform was less controversial.

It is impossible to say how many women belonged to the Atalanta Club, since no records remain. However, press reports suggest that it thrived:

At the end of the first year the club was in an extremely flourishing condition, there being thirty-one active and six honorary members, and the state of affairs was even more satisfactory at the completion of the club's next year's existence. [3]

Middle class women, both married and single, predominated in cycling. Among club members were a number of 'New Women', such as dress reformer Kate Wilkinson (born Walker), and Edith Mary Statham, a founding member of the Dunedin branch of the Society for the Protection of Women and Children. When Statham moved to Dunedin around 1895, she quickly established the Mimiro Ladies' Cycling Club, and acted as its secretary. For several years she ran a school to teach women to cycle.

The cycling season in Christchurch commenced each October with a 'run', at which all the local clubs would appear in uniform and proceed through the city, watched by thousands of spectators. During each season the Atalanta Club organised one- or two-day trips; it also hosted social functions—balls, card evenings, picnics, and 'At Homes'—at the club rooms in Hobb's Buildings. In addition to its recreational merit, the bicycle afforded women an independent means of transport for business or tourism. Women frequently cycled together on long trips, usually accompanied by husbands or brothers. It was not uncommon to visit the West Coast or tour the South Island.

If dress reform was controversial, women's cycle racing was treated with contempt. When Burn entered a road race in Ōamaru in December 1892, she was viciously censured by pro- and anti-cyclists alike, including members of her own club. But she vigorously asserted 'a woman's right to do exactly as she pleases in spite of the strictures of a conventional majority'. [4]

It took great courage for those women to mount their bicycles, for they encountered frequent hostilities. Abused and jeered at, some were even pushed off their bicycles. At times male friends would have to accompany them to ward off stone-throwing objectors.

Despite its popularity, and that of cycling generally, the Atalanta Cycling Club ceased to exist somewhere between November 1897 and October 1898.

Clare Simpson

Notes

[1] Canterbury Times, 7 January 1897, p. 25.

[2] It is not entirely certain that this was in fact Kate Sheppard. She would have been 44 when the Atalanta Club was formed, but many women of that age and older did take to cycling.

[3] New Zealand Cyclist, 26 June 1897, p. 26.

[4] New Zealand Wheelman, 28 January 1893, p. 10.

Unpublished sources

Interview with Blanche E. Thompson, Radio New Zealand Sound Archives, c. 1961

Simpson, Clare, interview with Ngawi Thompson, Rangiora, 1989

Published sources

Malthus, Jane, '"Bifurcated and not Ashamed": Late Nineteenth-century Dress Reformers in New Zealand', New Zealand Journal of History, Vol. 23 No. 1, 1989, pp. 32–46

New Zealand Cyclist, April 1897–December 1899

New Zealand Wheelman, October 1892–September 1902

Community contributions