This essay written by Sonja Davies and Mary Sinclair was first published in Women Together: a History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand in 1993.

The New Zealand Working Women's Council (WWC) was formed to promote the interests of working women. Its greatest achievement was the successful campaign to have the labour unions accept as official policy its Working Women's Charter, essentially a Bill of Rights for all women.

The origins of the WWC lie in Sonja Davies' 1974 visit to Israel, where she was impressed by the Israeli Working Women's Council. Funded by a percentage of all union fees, the council provided a wide range of facilities and support services for women and their families. [1]

Back in Wellington, Davies and a small group of women decided to form a New Zealand Working Women's Council, its aims reflected in the slogan 'Equality, Education, Action'. The first concern was funding. Aware that the male-dominated New Zealand union movement was not ready to consider the Israeli model, Davies approached Tom Skinner, president of the Federation of Labour (FOL), and Prime Minister Bill Rowling in August 1975. To her surprise, Rowling offered her $80,000 in the 1976 budget.

The founding group became the nucleus of the council, with Davies as chairperson, Rosemary Te Heu Heu as secretary, Mary Sinclair as press officer, and Margaret Shields on the committee. Davies also enlisted the support and experience of prominent women trade unionists and politicians she had met overseas. When approached, the FOL executive endorsed the council 'in principle'.

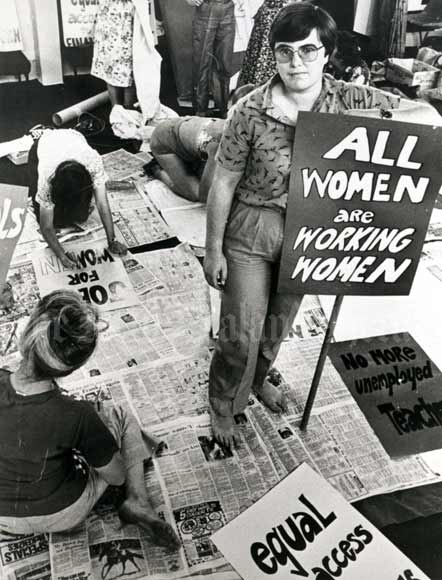

Branches soon formed in Canterbury, Auckland, Tokoroa, Gisborne and Petone. Contrary to later accusations by its detractors, the council always aimed to encompass both women working in the home and those in paid employment; it also wanted to involve women from all sections of society—not just the middle classes.

Labour's defeat at the 1975 election, and an unsympathetic incoming Cabinet, meant that the promised funding did not eventuate. This made the new council's task daunting, especially as the subscription fee was deliberately kept low. Some trades councils and individual unions responded to requests for help, but most were initially suspicious of the council's motives. Women were assumed to be anti-union because they seldom attended union meetings; but union leaders failed to understand that this was partly because meetings were usually held in the evening, when most women were at home attending to their household and family responsibilities.

In 1976, as council members began planning a Working Women's Convention for the following year, they were encouraged to learn that an earlier Working Women's Convention had been organised by Freda Cook, Elsie Locke and Connie Birchfield in 1932; the issues discussed then had been substantially those planned for 1977. Davies attended a similar conference at Macquarie University in Sydney in 1976, and brought home a copy of a proposed Working Women's Charter. The organising committee decided to adapt it to local needs and make it the focus of the convention.

Over 400 women attended the convention in Wellington in March 1977, including a strong Australian delegation. The final session overwhelmingly adopted the Working Women's Charter, including the two most contentious clauses, calling for the abolition of restrictions on safe abortion, contraception and sterilisation, and for the introduction of more flexible working hours and part-time work opportunities for all workers. The council then embarked on a vigorous and exhausting campaign to get the charter accepted by the union movement. For over two years it was to be the focus of more attention and debate than any other union issue.

At the 1978 FOL conference the New Zealand Shop Employees' Association, which had adopted the charter at its own annual conference, submitted a remit asking for the charter to be adopted as FOL policy. Despite the all-male policy committee's initial rejection of the remit, delegates agreed to refer the charter to affiliated unions and district trades councils for discussion, and to reconsider it at the 1979 conference.

It was clear from the 1978 conference debate that male union leaders had not really discussed the charter and did not realise how strongly women felt about the issues. But the response of women all around New Zealand to the challenge of getting the charter adopted showed how closely they identified with its aims. In both the union movement and the Labour Party, they arranged meetings and seminars on the charter, sometimes in the face of strong opposition from male members. In some centres, however, men were supportive.

During 1978–79 council members, particularly Davies, travelled around the country speaking to workers and Labour Party members. At the 1979 FOL conference, although some unions had still not discussed the charter, Skinner moved that it be approved 'in principle', suggesting that those trades councils which had not yet held seminars should do so.

Despite the continuing opposition of some union leaders, [2] delegates at the 1980 FOL conference voted overwhelmingly to adopt the Working Women's Charter as FOL policy. Delighted telegrams and letters poured in from women. A week later, the Labour Party's annual conference adopted the charter, but also agreed to hold a referendum on the abortion issue after the election.

New Zealand Herald 23 Feb. 1981 (sourced from Te Ara).

Sandie Beatie, national convenor of the Working Women’s Council, displays a banner to be used in a silent ‘Women and Work’ march up Queen Street, March 1981. Many Auckland women’s groups participated in this public show of support for the Working Women’s Charter.

The anti-abortion lobby promptly mounted a strong campaign against the charter; its widely circulated pamphlets claimed, among other things, that it was a communist document. Catholic and other traditional churches mounted their own campaigns. A small Dunedin group, having discovered that the WWC was not registered as an incorporated society, stole the name, registering itself as the New Zealand Working Women's Council Inc. The real council protested to the Registrar of Incorporated Societies and eventually had the name returned, long after the council had ceased functioning. By May 1980 lack of finance and confusion over the name had made the council unable to continue; their primary goal achieved, members were also becoming involved in other organisations and priorities.

Despite its short existence, the council had a significant impact on the labour movement. Once the major labour organisations, including the PSA and PPTA, had adopted the charter's aims as official policy, they began forming women's committees and electing women to their executives. But although they took the issues seriously, by 1993 much remained to be done to promote the interests of women at work, wherever that might be.

Sonja Davies and Mary Sinclair

Notes

[1] The Israeli Working Women's Council, with over a million members, provided 27 community centres, 257 women's clubs, a counselling bureau for bereaved families, three legal counselling bureaus, and daycare nurseries, kindergartens, and day and night homes for 20,000 children.

[2] Chief opponents of the charter were Tony Neary of the Electrical Workers' Union and Pat Kelly of the Cleaners' and Caretakers' Union.

Unpublished sources

New Zealand Working Women's Council records, 1975–1980, National Library, Wellington

Published sources

Davies, Sonja, Bread and Roses, ANZ Book Co/Fraser Books, Auckland, 1984

Sinclair, Mary (ed.), Women Workers in New Zealand, New Zealand Working Women's Council, Wellington, 1977

Community contributions