This essay written by Charlotte Macdonald was first published in Women together: a history of women's organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Charlotte Macdonald in 2018.

In a country renowned for its sporting traditions and fervour, women's sport and recreation organisations tended for decades to occupy the status of 'also-rans' in a field of more illustrious competitors. [1] Yet they have a long and varied history dating from the late nineteenth century. Their lower profile belies the central place they have occupied in the lives of a very large number of New Zealanders and local communities. In 1993, membership of the three largest groups – the New Zealand Women's Bowling Association, the New Zealand Ladies' Golf Union and Netball New Zealand Inc. – was 30,000, 35,000 and 106,600, respectively. [2] They comprised some of the largest and longest established national women's organisations in New Zealand's history.

Organising for enjoyment was a relatively late priority for women in colonial New Zealand. The first organisations for women's recreation date from the late 1880s and 1890s, some time after women organised to provide welfare or to share common religious beliefs. This does not reflect any reluctance to take part in sports events: in 1849 crews of Māori women took part in a whale-boat race on Port Chalmers for which the trophy was a silver teapot, and from the 1850s and 1860s women were eager participants in the Anniversary Day and New Year holiday sports. It was not, however, until the 1880s and 1890s that separate organisations were formed to foster women's sporting interests. Until around 1920, such organisations were little more than small enclaves of enthusiasts. These early years can be thought of as the foundation period, the first of four broad phases of development in the history of women's leisure and sporting organisations.

From around 1920 to the late 1930s, organisations for girls' and women's sport and leisure proliferated as public attitudes changed: the sportswoman was no longer regarded as a social novelty, and exercise and fitness were seen as likely to enhance, rather than endanger, the health of New Zealand's women and girls. In this second phase, organisations for young women (the YWCA, Girl Guides, The Girls' Brigade and Girl Citizens) flourished, as did women's clubs, which drew their members from slightly older women, of more comfortable social backgrounds.

During the third phase, from the late 1930s to about 1970, the number of women's sporting and leisure organisations continued to grow; but equally important was the emergence of an institutional and increasingly national framework for sporting and leisure activities. Government involvement in sport and leisure became significant through the work of Physical Welfare officers within the Department of Internal Affairs, the emphasis given to fitness during the Second World War, and the introduction of a national physical education curriculum in the 1940s. These developments were particularly important for women's sporting organisations, which generally had less financial and administrative backing for their activities than did men's leisure and sporting bodies. Sports which were very closely associated with New Zealand girls and women arose in this period, paramount among them being marching.

Separate organisations begin: 1880s to 1910s

Over the 1970s and 1980s, the patterns established in the earlier periods were substantially altered by the advent of feminism, the commercialisation of sport, and broad shifts in the ways in which New Zealanders spent their leisure time. These all brought considerable change to existing organisations and, to a lesser extent, stimulated the emergence of new groups.

The earliest women's sporting and leisure clubs and organisations arose at a time when the whole nature of women's capacity and place in political and social life was a matter of general debate. Physical education was either non-existent, or confined to routine drill – or simply breathing exercises while sitting at a desk. Eminent figures such as Dr Frederic Truby King (founder of the Plunket Society) publicly expressed grave fears about the detrimental effects which were likely to ensue from women and girls exerting their brains, let alone their bodies. In this context, vigorous physical exercise in sport was by no means something which met with general acclaim. In the 1890s a few clubs – notably the cycling clubs – were founded with the overt aim of claiming for women the right to physical freedom and independence, as part of the larger feminist agitation for full citizenship and in particular political enfranchisement. Those who sought opportunities to play golf, hockey, bowls and to race in boats together on a regular basis were also social pioneers.

The first women's sport and recreation organisations were formed in the late 1880s and 1890s under the twin impetus of a general growth in organised leisure (sports clubs and regular competition replacing the all-in community sports days of earlier decades), and an expansion in opportunities available to women and girls in education, employment and public life generally. The most popular sports for women in late-nineteenth-century New Zealand were croquet and tennis. Clubs such as the Parnell Croquet Club, founded in 1872, and the Christchurch, Central and Western Croquet Clubs in Christchurch (1873), attracted a predominantly female membership from their inception. By the 1880s tennis had superseded croquet in popularity, and was attracting an enthusiastic following among colonial girls and women.

The tennis and croquet clubs reflected the essentially social origins of these games as extensions of drawing-room amusements for the wealthier sections of society. These clubs, and later the regional and national organisations they gave rise to, had mixed-sex membership, and continued to do so into the 1990s. [3] This was the pattern, in fact, for the majority of sports in which women participated. Swimming, athletics, badminton, gymnastics and softball, as well as tennis and croquet, were all administered by a single body within which men and women competed separately. However, the much smaller group of activities where men and women organised independently contained the organisations with the largest memberships – Netball New Zealand Inc. (originally the New Zealand Basketball Association) and the New Zealand Rugby Union.

Women's hockey clubs formed in Christchurch (Kaiapoi Kiwi Girls' Hockey Club and Hinemoa team, 1897), Auckland (Wapiti Club, 1899) and Nelson (Wakatu Club, 1897) in the late 1890s. They were made up mostly of younger women who were introduced to the game at secondary school by a few enthusiastic teachers. The number of hockey clubs grew gradually over the next few years, with local associations forming in a number of areas to co-ordinate competition. Six clubs came together to form the Otago Ladies' Hockey Association in 1906, and two more joined the following season. In 1908 the 10 local associations formed the New Zealand Ladies' Hockey Association (NZLHA), whose main task was to regularise rules and uniform.

In these early years, debates took place over the role of men in the local and national hockey associations, and the possibility of the women's hockey association amalgamating with the men's. The Otago association rejected a proposal of amalgamation in 1910. Cora Maris Clark, a key figure in the growth of hockey in both Otago and Auckland, strongly argued that women's hockey should be administered by women; but her proposal that all office-holders in the NZLHA 'should be ladies' was firmly rejected by other delegates at their inaugural meeting. [4] A number of men did hold office in the association, and acted as umpires. In 1914 the NZLHA hosted the first and most significant major international women's sporting event prior to 1920: the highly successful tour to New Zealand of an All-England Ladies' Hockey Team.

The only other sport to establish a national organisation in this period was golf. The combination of healthy outdoor exercise and sociability made golf attractive to wealthier colonists in the same way as croquet and tennis. Women were enthusiastic players from the time courses were established in the early 1890s, but the men's clubs which initiated the sport were not, on the whole, keen to include women players on an equal basis. The different tradition associated with the game meant that men's and women's clubs developed in what can be described as an unbalanced parallel. Women were not generally admitted to the men's clubs, and soon formed their own, negotiating access to courses and the facilities of the men's clubs on a variety of terms.

The Auckland Ladies Golf Club, formed in 1896, enjoyed a brief autonomy, leasing paddocks in Epsom for their course. Unfortunately the owner of the land required the ground the following year. The club, which had 'unanimously negatived' the proposal that men should be office-holders, and had relegated men to the status of 'casual members only' the preceding year, had little option but to request access to the Auckland men's course in order to continue playing. [5] Nevertheless, the ladies' clubs evidently desired independence in playing rules, conditions and organisational framework. They affiliated to the British-based Ladies Golf Union in 1905, and subsequently formed the New Zealand Ladies' Golf Union (NZLGU) in 1911, before and in preference to any further organisational links with the men's New Zealand Golf Association (formed 1910).

Boat racing was another sport which had its origins in English public school and college traditions, but it took on an everyday importance in New Zealand, where sea and rivers constituted the major transport routes throughout the nineteenth century. Little is known about the Christchurch Girls' Boating Club, which was reported to be resuming its activities in the spring of 1887, and was still meeting for a weekly 'pull' up the Avon in 1893 (usually followed by a tea-picnic), or about the Picton Ladies' Boating Club, which formed in 1888; but it is clear that these were not the only oarswomen in the country at this time. In the 1890s, women's crews competed in regattas organised by the Waitara Boating Club, and there was an annual whale-boat race between Auckland and Waitara ladies' crews. Ladies' events were also held in the early years of the twentieth century in Taranaki, where the Clifton Rowing Club was particularly prominent.

The strongest following for bowls in this early period – not surprisingly, given the game's Scottish origins – came from Dunedin; but the first women's bowling club started in Wellington, in 1906 at Kelburn. Bowling circles tended to grow out of croquet or tennis clubs, and women keen to play the game found they encountered the same kinds of problems as women golfers, in having to negotiate with the men's clubs for access to greens and facilities. The real growth in women's bowling clubs came at a later period.

Perhaps the most celebrated, though rather short-lived, organisations in this period were the women's cycling clubs, which formed in the 1890s. The Atalanta Club of Christchurch, the Mimiro Club in Dunedin and the Auckland Ladies' Bicycle Club [6] symbolised, far more than any other body, the conjunction of women's physical and political emancipation. The women who founded the Atalanta Club included Kate Walker and Alice Burn, leading exponents of dress reform – one of the most radical aspects of the emancipation movement. The club provided valuable solidarity for women who dared to tackle the new skill of riding the bicycle – a novel and certainly extremely conspicuous form of physical exercise. It also reflected the wider aspirations articulated by many New Zealand women in the 1890s, not only for political enfranchisement but also for a degree of physical freedom and independence.

Basketball (later netball) was also played in New Zealand from the late 1890s, but the first organised competitions and clubs did not start until shortly before the First World War. The first women's clubs also appeared in the 1890s. The oldest club still in existence in 1993 was the Ranfurly Club of Masterton, which began in 1899 as a place where women could meet and refresh themselves. Within a few years Wellington had its Pioneer Club (1909) and Christchurch its Canterbury Women's Club (1913), while Dunedin was home to the Otago Women's Club (1914). Basing themselves on organisations in England, America and Australia, these clubs were designed to offer women of superior social standing a place for social and, to some extent, intellectual companionship.

Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, AWNS-19210915-42-1.

Aotea Soccer Team, Wellington, 1921. The team members were women workers at a shirt factory in Wellington; they were considered 'pioneers in ladies' football'.

In the wake of the First World War, the influenza epidemic, and escalating concern about a continuing decline in the birthrate, there was a marked change in attitudes towards women's sport and recreation. Rather than being seen as potentially damaging, physical exercise and fitness were increasingly regarded as essential to health. By this time also, as New Zealand's towns and cities grew, larger numbers of young women were working set hours in shops, factories and offices, with access to networks of public transport and communication (including the telephone). Sport as a form of leisure has appeal only when daily toil does not involve large amounts of physical exertion. This was increasingly the case for girls and women growing up in the 1920s and after. These factors lay beneath the tremendous growth in both the number and size of women's recreation and sporting organisations between the wars, as they passed from being small circles of devotees, mainly from leisured middle class backgrounds, to attracting a large popular following. 'Ladies' gave way to 'women' in the names of organisations: the Otago Ladies' Hockey Association, for example, renamed itself the Otago Women's Hockey Association in 1935.

Foremost among the organisations which flourished in this period was the YWCA, which gave special emphasis to its recreation programme and employed physical instructors as professional staff. These women, who generally had specialist training in physical education, introduced a range of new sporting and physical activities. They were particularly successful in using the YWCA's organisational structure and gymnasium facilities to foster extensive team competition, particularly in hockey and basketball. From this competition emerged the Interhouse Sporting Associations, where young women competed in a variety of sports in teams drawn from business houses. These became large-scale events in this period, attracting crowds of spectators to the massed displays, as well as arousing keen rivalry between the teams themselves. The YWCA also acted as an umbrella organisation, supporting new sports and activities and, when these had attracted a sufficiently strong following, fostering the establishment of independent organisations.

A number of sports which had been played only at a local level established national organisations and tournaments in this period. The most notable was basketball, which grew very rapidly in the 1920s and 1930s, becoming indisputably the major winter game for New Zealand women and girls. A first attempt in 1923 to form a national body failed; but in 1924, representatives of three of the four local associations met in the YWCA rooms in Wellington to form the New Zealand Basketball Association. [7] By 1935, the four founding affiliate associations had grown to 25. The national body organised an annual national tournament from 1926, and was the first New Zealand women's sporting organisation to send a representative side to tour overseas, when Meg Matangi led the New Zealand team to Australia in 1938.

For those who had more leisure, more money and were generally a few years older, the sport which really caught on in the 1920s and 1930s was golf. Between 1928 and 1938, the NZLGU doubled in size to 232 clubs and over 14,000 members. The 1930s were a real heyday for golf, reflected in both popularity and the level of competition.

Women cricket players also formed a national organisation in this period. While women had played cricket in New Zealand as early as the 1880s (largely at girls' secondary schools), not until 1928 did the first provincial association form, in Auckland. Five years later, with a tour by an English team pending, the New Zealand Women's Cricket Council was founded.

Three organisations for young single women – Girl Guides (1923), The Girls' Brigade (1928) and Girl Citizens (1923) – all with a sporting or physical exercise component in their programmes, also date from this period (though some local groups were in existence earlier). Each was part of a larger international body. The integration of physical, intellectual, social and spiritual development was a central aim for all three, and in this sense, none was solely recreational in its focus. The emphasis was on participation rather than competition. Nonetheless, these were all organisations which sought to channel the leisure time available to young women; and those who joined saw opportunities to go camping, swimming and exploring with others of the same age as a major attraction.

Waitemata Girls’ life-saving team. Formed in 1935, the team patrolled Mission Bay, Auckland.

Women's surf life-saving teams were formed in the 1920s (possibly even earlier), [8] but the first club was not formed until 1932, when Kate and Alice Armitage set up the Milford Girls' Surf Life Saving Club. Clubs in Tauranga and North Shore appeared the following year, and in 1934 the Dominion Championships featured ladies' events for the first time. Other teams formed in the 1930s, but it was World War II which gave real impetus to girls' and women's surf lifesaving.

Proliferation of clubs: 1920s and 1930s

The 1920s and 1930s also saw the proliferation of clubs for slightly older women, mainly from middle class backgrounds. The primary purpose of these clubs (whose constitutions almost invariably declared them to be non-sectarian, non-political and non-partisan) was social: providing a place and time for women to meet together in a setting free from the obligations of private entertaining, where attendance was a privilege bestowed by membership rather than invitation. In part the clubs grew out of the activities of women's patriotic societies during the First World War, and the conviviality these engendered; but they also reflected a desire of many women for some focus of their own beyond the domestic realm.

Some clubs, primarily those in provincial centres such as Masterton and Feilding, offered overnight accommodation (used by women from the country on their visits to town), in addition to the usual meals and lounge facilities provided in most clubrooms. A number of clubs also sought to encourage a degree of literary or cultural activity by setting up circles for particular interests – bridge, gardening, drama, and the like. The Auckland Women's Club, for example, was inaugurated in 1919 by prominent Auckland lawyer and city councillor Ellen Melville, together with Jessie Gunson and Lucinda Wilson, in order to provide a forum for 'women interested in social, public and artistic affairs'. [9] After affiliating with the London Lyceum Club in 1922, it became known as the Auckland Lyceum Club. Initially it attracted over 700 women, though relatively few were active members, and even fewer took part in the kind of 'self-improving' activities which the founders had in mind. A Federation of Women's Clubs was inaugurated in 1925, primarily to facilitate the exchange and transfer of members between clubs throughout the country. While many clubs did choose to affiliate to the federation, a few, such as the Wellington Women's Club (1924), guarded their independence.

Institutions and frameworks: 1930s to 1970s

The period from the late 1930s to about 1970 is distinguished first by the growth of a broad institutional framework for sport and leisure, and secondly by generally prosperous economic conditions which vastly expanded opportunities for New Zealanders to take part in leisure activities, especially weekend sport. The first Labour government saw recreation as an entitlement of all citizens; its 1937 Physical Welfare and Recreation Act established the Physical Welfare Branch within the Department of Internal Affairs to stimulate recreational activities at a community level. [10] Health and fitness were transformed from social ideals to national priorities with the outbreak of war in 1939. At the end of the war, the vastly increased structure of physical training which had been part of women's auxiliary and civil defence training, and of armed service life, was institutionalised with the introduction of a national physical education curriculum in secondary schools, and the founding of the Physical Education School at the University of Otago (1947). These developments had a particularly important impact on women's sport, which had fewer private resources to draw on in establishing and sustaining sports and leisure clubs and activities.

This period was also one in which virtually full employment and a shorter working week brought more time and money to spend at the weekend and on non-essentials. However, the benefits to women were not always as great as might have been expected: these factors largely affected the full-time paid workforce (predominantly men and single women), and there was little questioning of married women's domestic obligations, which tied them to the daily and weekly round of childcare, cooking, cleaning and washing. With increasing numbers of women marrying at younger ages, the young women who had made up the membership of most sporting organisations instead found themselves married, with young children to look after, and no time or energy to spare for playing sport.

New organisations which emerged in this period include a national women's baseball tournament (1940), [11] the New Zealand Marching and Recreation Association (1945), the New Zealand Women's Indoor Basketball Association (1946), and the New Zealand Women's Bowling Association (1948). In all of these, women Physical Welfare officers played an important part. Baseball was played sporadically in the late 1930s at various places around the country: girls at the Auckland YWCA played from 1936, while teams at the Ford Motor Company in Petone played each other during their lunchtimes from 1937. A form of softball or baseball was also one of a number of new games promoted by the Physical Welfare officers, and was popularised by American servicemen in New Zealand between 1942 and 1944. Even before this, however, organised competition had begun: a national women's tournament was held in Wanganui in 1940. Through the 1940s the women's teams were increasingly drawn into the mixed-sex New Zealand Softball Association (formed in 1938), where the women's game fared well. The first representative team to compete internationally was a women's team which took part in the 1949 Victoria Softball Carnival in Australia. Softball continued to grow under the association as a sport for both women and men, who by 1993 were playing it in approximately equal numbers.

Out of the formation marching of the inter-house sports in the 1930s and the military preoccupations and drill routines of the war, there emerged in the 1940s the uniquely New Zealand sport of marching. Based on the discipline of team competition, it comprised a set of highly precise, synchronised turns, steps and moves, and was judged on presentation as much as physical skills. The sport received considerable direct encouragement from the government in its early years. Miriel Woods, a Physical Welfare officer, was instrumental in forming the national organisation, with wholehearted support from the Department and the Minister of Internal Affairs, and also from Prime Minister Peter Fraser and Leader of the Opposition Sidney Holland, who both became vice-presidents. Politicians attended the national championships of the marching association during the 1940s, and the government sponsored a film about marching to be shown in Britain.

Women's bowls, which up until this time was played largely at club and local level, and lagged a long way behind the men's game in facilities, organisation and membership, was organised on a national basis with the assistance of Physical Welfare officer Noeline Thompson. The inaugural meeting of the New Zealand Women's Bowling Association (NZWBA) was held in Dunedin in 1948. The first tasks of the newly elected officers included adopting a constitution and regularising playing rules between different parts of the country. By 1964, 20,000 women were affiliated to the NZWBA, playing in clubs organised in 21 centres throughout the country.

Audrey Henderson collection

Dorothy Fox (born Creak) and Audrey Bathe (later Henderson), members of the Women's International Motorcycle Association, at the start of the Ixion Motor Cycle Club's Two Day Touring Trial in Wellington, March 1956.

Very different from these organisations were the Women's International Motorcycle Association and the New Zealand Airwomen's Association, which attracted small followings in the 1950s and 1960s. [12] Operating as networks rather than large organisations with formal structures, these special interest groups indicated how the range of recreational pursuits expanded in general, and among women in particular, in this period.

While some established organisations increased their membership between the 1940s and the 1960s, others found that the changed conditions of post-war New Zealand made it more difficult to sustain their level of activity or even their existence.

The women's surf life-saving clubs, which had flourished in the 1930s and increased in number during the war, as women were called on to patrol the beaches, were in decline by the 1950s. Women's events were cancelled at the national surf championships in 1951 because of the lack of entries, and the Milford Club went into recess in 1961. Organisations which relied on attracting young women in their late teens and early twenties also struggled to survive; young people in this period were increasingly likely to spend their leisure time in mixed company outside the direct supervision of parents or adult leaders. A greater range of entertainments was available to them, and they preferred these to the single-sex sports and supervised sociability offered by organisations such as the YWCA. Similarly, the women's clubs which had attracted large memberships in the 1930s and 1940s began to find they were not drawing in new members at a level sufficient to cover the rapidly escalating costs of running rooms and facilities.

The impact of feminism: 1970s and 1980s

The upheavals which reshaped New Zealand's social and economic life over the 1970s and 1980s were reflected in the preoccupations of women's sport and recreation organisations. Three factors had particular impact: the challenge to traditional sexual divisions in sport and recreation prompted by the reawakened feminist movement; the increasingly commercial environment in which sports operated (especially the advent of commercially valuable television coverage); [13] and fundamental shifts in New Zealanders' patterns of leisure. The combined impact of these resulted in the remodelling and reorientation of existing organisations, rather than the formation of new ones.

From the early 1970s, in sport as in other areas of life, women were forthright in claiming the right to equal access, participation and recognition, and challenged traditional divisions between men's and women's sports. [14] There were many individual struggles and episodes; at an organisational level, it was clear that there had been some erosion of long-standing demarcations between men's and women's activities. The changes which resulted from this process, however, were by no means uniform.

In sports which had been largely male preserves, women generally made considerable headway in challenging the barriers to their participation. In numerical terms, the most successful example could be seen in the very rapid growth of women's soccer. The Women's Football Association was formed in 1975 to give the game a national structure. By 1991, when the association changed its name to the Women's Soccer Association of New Zealand (to avoid confusion with other football codes), it had 8000 members playing throughout the country, in grades from school to national competition level. [15] Women's rugby teams appeared as regular competitors in the early 1980s. Most of the 87 teams competing in the 1992 season had been absorbed within existing unions and clubs. The number of men who adopted the traditional 'women's game' of netball was much smaller, though increasing, while the modified games of touch rugby and commercially organised indoor netball became tremendously successful as new mixed sports. [16]

In outdoor recreation activities where the traditional pattern was one of mixed clubs (many dating from the 1930s), feminism stimulated the formation of separate women's organisations. Women on Water (1985), Women Climbing (1985) and Women Outdoors New Zealand (1988) were all formed to provide a specifically women's space in which those inexperienced in outdoor activities could try them out, and those with experience could develop leadership skills. The aim of all three organisations was to encourage women into activities from which they had never been absolutely excluded or absent, but in which they were a minority, with opportunities and confidence less available to them than to men. Important, too, was the idea of combining outdoor pursuits with an appreciation of the natural environment, rather than people pitting themselves against nature (and each other) while 'conquering' peaks and rapids. The new organisations attracted criticism from some men, and from a few women then active in mixed clubs, who saw them as divisive and unnecessary, and denied that any barriers existed to women's participation. Like other organisations for minority recreational pursuits, the three mentioned here operated as informal national networks, with a newsletter forming the key link between members.

The second major area of change between 1970 and 1990 arose in response to the increasing complexity and cost of maintaining national organisations and competition. Sports and recreation bodies which used to rely on the unpaid labour of administrators and coaches increasingly became professional, employing staff and developing a business-like profile. Traditional fundraising was no longer adequate to cover the cost of more frequent overseas tours and national fixtures. At the same time, sports coverage on television was growing in hours and in commercial value. The change from membership subscriptions and fundraising to sponsorship-based funding reached most sports in the 1980s. In the case of large organisations such as Netball New Zealand Inc., this meant negotiating multimillion dollar deals with corporate sponsors.

The institutional framework for sport and sports organisations also became more elaborate from around 1980. Organisations had to provide the means to support elite international competition while maintaining broad participation at community level. The latter involved staving off competition from other sports and promoting interest in their own codes through developing 'twilight', social grade, mid-week and KiwiSport programmes. The Sports Foundation and the Olympic and Commonwealth Games Association were concerned primarily with advancing high level competition. For recreation and sports organisations generally, the expansion of government involvement was critical. The Ministry of Recreation and Sport was established in 1973, and reconstituted as the Hillary Commission in 1987. By 1993 the commission was a major source of funding for sports bodies, and was particularly important for women's organisations, which in general lacked alternative sources such as gate takings, large-scale sponsorship (with a few exceptions), substantial membership subscriptions, or bar sales.

Faced with this increasingly commercial environment, some women's organisations opted for a greater economy of scale by joining forces with the parallel men's organisation, thus forming a stronger single organisation with which to attract sponsorship and rationalise the costs of administering national and international competition. It was for these reasons that the New Zealand Women's Hockey Association and the New Zealand Hockey Association merged in 1988 to form the New Zealand Hockey Federation. Similarly, though in a sport where the numbers of players, assets and profiles of the men's and women's games were much less even, the New Zealand Women's Cricket Council ceased to exist in September 1992, amalgamating with the governing body for men's cricket, the New Zealand Cricket Council. By 1993 the two national bowls associations were discussing amalgamation. This trend towards the formation of larger mixed organisations was occurring locally too: the Hamilton Ladies' Golf Club, for example, amalgamated with the Hamilton Golf Club in 1991, while in Feilding the men's club (with its more extensive facilities) opened its doors to women, thereby diminishing the place for a complementary women's club.

The merits or otherwise of amalgamation were a matter of vigorous debate within sporting circles. Those who opposed it feared the demise of women's autonomy in sporting administration as well as competition, particularly once officers whose experience was gained in women's organisations gave way to those with no such background. Its advocates, on the other hand, saw benefits accruing to women's sport through access to the generally better resourced men's organisations, and in particular the opportunity to break out of the vicious circle of low media profile/little sponsorship/modest performance within which women's sport had been trapped. In 1993 the changes were still too recent for their outcome to be fully evaluated.

Even with Hillary Commission and sponsorship support, however, well established sporting organisations had to work hard from the mid 1980s to retain their levels of membership. There seemed to be various reasons for this. One was simply that the number of sports and leisure activities available to New Zealand women and girls was expanding all the time. Commercially organised recreations such as indoor netball, indoor cricket, fitness gyms and dragon-boat racing, which drew largely on mixed, workplace-based teams, were proving attractive in their convenient venues and match times (generally mid-week and evenings). With weekend shopping and the extension of the working week into Saturdays, Sundays and evenings (particularly affecting the retail and service sectors, where many women were concentrated), organisations could no longer assume that potential players would be available for regular practices or games. High levels of unemployment, especially among young people who made up a high proportion of active sports participants, put pressure on individual and household budgets; the first items to go were usually 'extras' such as club subscriptions, and other costs associated with playing sport (match fees, gear, travel). It might also have been the case that New Zealanders were turning to more individual forms of recreation and leisure, pursued outside the ambit of any formal organisation.

The argument over amalgamation seemed likely to continue into the 1990s, as organisations faced the pressure of operating in a more financially rigorous environment. The battle for greater media coverage of women's sports generally was intensifying; in November 1992 it moved into the legal arena, with the lodging of claims by FIRST (Female Images and Representation in Sport Taskforce) with the Broadcasting Standards Authority. While the ways in which these issues were tackled had certainly changed over the years, the central problem for women's sports and recreation organisations was remarkably consistent: finding the material resources and facilities to support activities. This, and the overriding domestic obligations women had to fulfil, were the greatest impediments to the development of organised sport and recreation among them.

Charlotte Macdonald

1994–2018

Sport proved to be an arena of significant and conspicuous change for women over the quarter century from 1994 to 2018, achieved not so much through the establishment of new organisations as by the transformation of existing ones. While women and girls were playing a wider range of sports by the early 1990s, beliefs that physically combative codes such as rugby and boxing were unsuitable for females, and that motherhood and elite competition could not be combined, were still pervasive. Such notions were eventually swept aside. The unimaginable in 1993 – that female players would be the fastest growing sector within rugby union, and that nationally representative teams in rugby union (Black Ferns) [17] and rugby league (Kiwi Ferns) would be playing on professional contracts – had become a reality by 2018.

Such revolutionary change was the result of complex, uneven and sometimes contradictory forces. A field where differences between women and men often seem most apparent, sport also offers a stage for female achievement, adulation, and cutting through barriers of gender, race, ethnicity, age, religion and ability. [18] By 2018 the success of contemporary female athletes, including Lydia Ko (golf), Valerie Adams (shot put), Lisa Carrington (kayaking), Sophie Pascoe (swimming), and inspirational leaders such as Laura Langman (netball) and Fiao’o Fa’amausili (rugby), had powerfully demonstrated the prominence, accomplishment and diversity of New Zealand women on the global stage.

Social change, ignited by the reactivated feminist movement from the 1970s, enabled subsequent generations of girls and women to pursue sports, recreation and leisure activities on a less rationed and differentiated basis than their predecessors. By 2017 women and girls were reporting similar levels of active recreation and sport as men at most age levels (and surpassing men in the 50–64 age group), though with less concentration than men on competitive sport. [19] The landscape in which sporting organisations supported such participation, at both community and elite level, had altered markedly since the early 1990s. The advent of professionalism within the major sports, the end of tobacco sponsorship, and, crucially, the substantial increase in public funding for sport, exerted pressure which, in some areas, was to the benefit of women. In return for greater funding from central and local government (through local authorities, SportNZ, High Performance Sport New Zealand and their predecessors), [20] national sporting organisations were required to meet targets for more equitable participation and greater diversity within memberships (players, coaches, administrators). Leverage exercised through the balance sheet produced results where the old membership-driven model had proved resistant to reform, enabling some sports to become leaders rather than followers of social change.

Integration, inclusion and standing alone

Hockey, cricket and bowls, all long-standing sports with separate women’s and men’s organisations and competitions, were poised on the brink of amalgamation in the early 1990s, and the trend towards integration continued. Separate national organisations for women’s and men’s golf ceased in 2005, bringing to an end the long life of the New Zealand Ladies’ (from 1996 Women’s) Golf Union, founded in 1911. Integration brought economies of scale, greater appeal to sponsors, and in some codes (perhaps most obviously bowls and cricket), made the greater resources of the men’s game available to women. For well-established, traditional sports such as these, amalgamation was also a response to the challenge of competition from a widening array of sports and active pastimes, many of which were offered on a casual or pay-as-you-play basis which was more attractive for girls and women with variable study, work and family routines. Commercial gyms and event-based activities, such as adventure races, triathlons, and runs-around-the bays, were vying with membership organisations.

While there were clearly some gains for women athletes and players through amalgamation, there were mixed results in terms of women’s representation in management, governance and coaching. Women exercising leadership roles in customarily male enclaves remained unusual enough to draw attention. Debbie Hockley’s appointment as president of New Zealand Cricket and Farah Palmer’s place on the board of Rugby New Zealand (both in 2016) drew headlines. At management level, Raelene Castle and Therese Walsh broke through the assumption that only men could manage ‘prime’ sporting events. Castle became the first woman CEO of an NRL club (and went on to become the first woman chief executive of Rugby Australia), having previously headed Netball New Zealand; Walsh served as chief operating officer for the 2011 Rugby World Cup and headed the organising body for the 2015 World Cricket Cup. While sport proved to be a place where women could pursue internationally competitive careers on and off the field, it also showed that it was not immune to the bullying and sexual harassment present in other high-pressure workplaces. In 2018 two major sports, football and hockey, were conducting independent inquiries into such behaviour by male coaches towards female players in their national squads. [21]

Netball New Zealand remained the largest and most high-profile women’s sporting organisation, with a predominantly female playing, coaching, management and governing base. Successfully navigating the transition to professional or semi-professional competition at the elite level in the mid-1990s, the sport did much to develop what had been the largely uncharted potential of commercial sponsorship for women’s sport. It remained the only women’s sport regularly gaining live coverage on television, and perhaps the only female team sport in which at least some of the national squad (the Silver Ferns) and their coach were consistently attaining the status of household names. Yet netball also struggled to grow at an international level, while global games such as football opened up a wider ambit of participation and profile for followers as well as players. Even more under pressure in a time of growing globalisation, conveyed powerfully through paid television and later through internet streaming, was the local code of marching and its more conventional feminine culture of display. [22]

Perhaps the most dramatic change in how and where women organised around sport came in the impact of women’s growing participation in dismantling the various football codes as bastions of male presence and culture, with Māori and Pasifika women team members playing a prominent part in both rugby union and rugby league. In a move inconceivable throughout most of New Zealand’s history, in 2018 New Zealand Rugby marked the 125th anniversary of women’s suffrage with a ‘Wahine Round’ in Week 6 of the major provincial competitions for the Mitre 10 Cup (men) and Farah Palmer Cup (women). [23] Running from 19 to 26 September, the week was designed to ‘celebrate the roles, involvement and contribution of wāhine (women) in rugby, including players, coaches, referees, fans and volunteers’. [24] While undoubtedly in part a celebration of the massive success of the Black Ferns (15-a-side and 7-a-side) as world champions over a number of years, this also recognised that the greatest growth in the game was evident in its female rather than male players, with a 14.6 per cent increase between 2017 and 2018 alone; meanwhile the number of male players remained static or declined, including in the key age bracket of 13–20 year olds. [25] New Zealand won the right to host the 2021 Women’s Rugby World Cup against Australian competition in November 2018.

In rugby league, women and girls also proved eager and successful competitors. In August 2018, a 22-woman squad was named by the New Zealand Warriors to compete in the first NRL women’s premiership. As the Warriors’ general manager, Brian Smith, noted in making the announcement, this was a chance for the club to ‘have a shot at history’. [26] The Kiwi Ferns, the national women’s side, first selected in 1995, enjoyed much success. As in netball and men’s league, their keenest rivalry was with their Australian opponents, the Jillaroos.

Football (soccer) was the first of the previously men’s games to be taken up by girls and women. In the past 25 years the number of women and girls playing football and the related game of futsal has continued to rise.

As the largest global sport, football has a wide reach not only in sport but also in popular culture. Football New Zealand was by 2018 claiming to be the most played team sport in New Zealand, with an estimated 210,000 recreational plus around 150,000 registered players. The women’s game grew by 35 per cent between 2012 and 2017, with women’s futsal the fastest growing sector. [27] The national side, the Football Ferns, had notable international successes, beating Thailand 5–0 in 2017 and consistently ranking in the top 20 nations, significantly higher than the men’s team.

Sport as a force of inclusion, and a place demonstrating diversity, also became evident in the greater profile and integration of paralympic sports and athletes, and the growing scale of events such as Outgames (an LGBT competition), Masters Games, and sporting events associated with marae, mosques and migrant or ethnic community events. Against these gains, there were also retractions in sporting, recreation and leisure opportunities. Sharply rising inequalities in New Zealand society as a whole reduced some girls’ and women’s access to leisure and sport, as well as polarising health indices. Rises in obesity, asthma, allergies and other conditions related to deprivation and environmental damage presented both obstacles to physical exercise and prompts to programmes addressing such inequalities.

Across the socio-economic spectrum, issues relating to body image remained disproportionately challenging for girls and women; in their most severe form they could result in crippling self-harm and eating disorders, but more commonly they also served to discourage women and girls from participating in active recreation. Programmes such as GirlGuiding New Zealand’s ‘You Be the Guide’ (2018) can be seen as responses to such contemporary conditions. The programme was designed to install self-confidence and, in particular, an acceptance of physical variety rather than social conformity.

Stuff Limited

Jodie Reed, aka 'Tank', of Nelson's The Sirens of Smash, in action against the Richter City Convicts of Wellington during a roller derby match at the Tahunanui Skate Rink, 2017.

Women meeting together on an informal and casual basis for leisure and physical recreation continued through social tennis; walking, cycling and tramping groups; bridge circles; and many other pursuits. New means of connecting up through online circles fostered such activities, and stimulated new movements as much as organisations such as Frocks on Bikes and the 261 Fearless group designed to support women marathon runners. [28] Some of these had an international reach. Roller Derby, played on roller skates, was a women’s sport (though there was one male team) new to New Zealand; it had revived first in the United States and was being played at competitive league level and on a national representative basis by the second decade of the twenty-first century. The sport cut through many orthodoxies with its culture, its outfits, and the names chosen by players (Ivy K’Nivey, Blockness Monster) and teams (Mascara Massacre, Broadside Brawlers).

A series of significant breakthroughs in 2018 offered some grounds for hope that women’s interest and success in sport would translate into more equitable levels of material and cultural reward. Rugby’s Black Ferns (15s and 7s) were offered substantially enhanced professional contracts, and the 15s played in joint fixtures with the All Blacks in Sydney and Auckland in September. Women in rugby league achieved their own professional competition and a place in the NRL club series. In football, Dunedin Technical beat Forrest Hill Milford (Auckland) 4–2 in the national knockout tournament to win the Kate Sheppard Cup, renamed in the suffrage anniversary year.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Eph-D-WOMEN-1998-01.

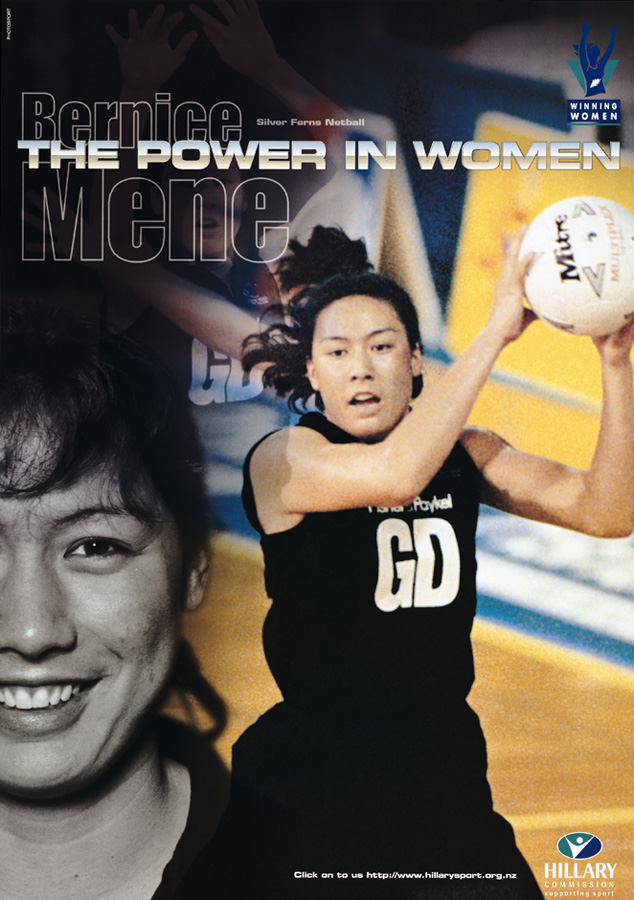

The Winning Women programme was intended to encourage women and girls to participate more in sport. Netballer Bernice Mene supported the programme by appearing on a Winning Women poster around 1998.

Success in sport also proved to be a path to other roles in public life, with Susan Devoy, Bernice Mene, Louisa Wall and Farah Palmer amongst those taking up political, business and public service leadership positions. These gains were built on many years of often pathbreaking and courageous steps into the unknown. Considerable work remained to be done for women’s sport to gain anything like parity in media coverage with men’s events, but there was some movement to shrink the gap, and a renewed urgency around addressing equality in this key area of national life.

In 1892, Kate Sheppard was arguing for women’s political right to equality at the same time as many men around the country were forming the New Zealand Rugby Football Union. In 2018, multi medal-winning Paralympian cyclist Emma Foy stood alongside Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern at the parliamentary reception to celebrate 125 years of the women’s vote, speaking confidently about the future for women on and off the sports field.

Charlotte Macdonald

New Zealand tandem paracyclists Emma Foy and Laura Thompson discussing their training and relationship after their selection for the Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. They went on to win a silver medal in the women's B 3000m individual pursuit. Emma, the stoker, is vision-impaired and Laura, the sighted pilot, has a congenital hip disorder.

Notes

[1] I would like to thank the following for their help in preparing this article: the Internal Grants Committee of Victoria University and Helen Walter; also the History Department of Victoria University; and Mary-Louise Ormsby, Clare Simpson, Ruth Fry, Rona Bailey, Allan Laidler, Jill Ford, the authors of entries in this chapter and the many officers and former officers of sporting and recreation organisations who assisted with queries.

[2] Figures supplied to Women together, 1991–92.

[3] The Carisbrook Lawn Tennis Club, formed in Dunedin in the 1880s, had 50 women members in its total membership of 150. The New Zealand Lawn Tennis Association was formed in 1886. It changed its name to New Zealand Tennis Inc. in 1988, and in the 1991–92 season had 56,149 affiliated members, of whom 27,803 (49.5 per cent) were women. The New Zealand Croquet Council was not formed until 1920, though local associations (especially in the South Island) existed long before this. In 1992 there were 21 associations and 4217 members affiliated to the council.

[4] Hammer, 1990, p. 45.

[5] Hammer, 1990, pp. 14–15.

[6] Little is known about this club, though there is at least one surviving photograph in the New Zealand Historical People, 1898 (Historic Photo Contest 1964) collection, News Media Library, Auckland.

[7] See entry for details of the association's subsequent changes of name.

[8] See, for example, photograph of 1912 life-saving team, negative number G41061/1, Pictorial Reference Service, ATL.

[9] Kuitert, 1986, p. 121.

[10] The Physical Welfare Branch lasted until 1954, when it was disbanded, and youth officers took over some of its activities.

[11] Coney (1986, p. 185) refers to the formation of a New Zealand Women's Baseball Association, but no further evidence could be found of an association being established at this point, though there certainly was a national tournament.

[12] 'Women's International Motorcycle Association: A Brief History', typescript, WIMANZ, c.1990. Information supplied by New Zealand Airwomen's Association (Inc.) to Women together, 1992. The Airwomen's Association was formed in 1959 and in 1993 had 280 members.

[13] For discussion of this at an international level, see 'The Sports Business: Faster, Higher, Richer', The Economist, 25 July 1992, pp. 2–18.

[14] An important colloquium on this subject was the Women and Recreation Conference held in 1981. See Papers and reports from the conference on women and recreation 31 Aug. – 3 Sept., 1981, New Zealand Council for Recreation and Sport, Wellington, 1981.

[15] See Jenny Lee, 'The History of the N.Z. Women's Football Assoc. Inc.', Diploma of Recreation and Sport project, Victoria University of Wellington, 1989.

[16] In 1993 there were approximately 70,000 registered touch players, around 30 per cent of them women. Information from New Zealand Touch Association (established 1984), 1992.

[18] Greg Ryan and Geoff Watson, ‘And Sport for All? 1990–2015’, in Sport and the New Zealanders: a history, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2018, pp. 283–309; Charlotte Macdonald, ‘Ways of Belonging: Sporting Spaces in New Zealand History’, in Giselle Byrnes (ed.), The new Oxford history of New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 269–96. The influence of a film such as Gurinder Chadha’s Bend it like Beckham (2002) illustrates the capacity of sport to subvert hierarchies. The film was situated in a British context but, like its eponymous hero, had global impact.

[19] Active NZ. the New Zealand participation survey, SportNZ, Wellington, 2018. Available from https://sportnz.org.nz/research-and-insights/surveys-and-data/active-nz/

[20] Hillary Commission 1987–2002; SPARC 2002–2012; Sport New Zealand and High Performance Sport New Zealand (HSPNZ), 2012–present.

[21] Employment lawyer Phillipa Muir conducted the independent inquiry into allegations at New Zealand Football. In her report, released on 3 October 2018, the organisation was condemned for a number of breaches of employment practices and presented with a comprehensive list of recommendations requiring wholesale culture change. Accessed 25 October 2018 from: https://www.stuff.co.nz/sport/football/domestic/107560554/review-into-nz-footballs-conduct-and-culture-set-to-be-released

[22] Paid television began in 1990, but was still in its infancy in 1993. The major provider, SKY Television, used sport as its prime product to sell subcriptions.

[23] New Zealand Rugby was originally the New Zealand Rugby Football Union (formed in 1892), then the New Zealand Rugby Union. Four of the five Farah Palmer Cup matches played during the week were shown live on SKY TV.

[24] All Blacks, 'Wahine round to celebrate role of women in rugby', press release, 17 Sep 2018. http://www.allblacks.com/News/33082/wahine-round-to-celebrate-the-role-of-women-in-rugby

[25] Of the 157,218 registered players in rugby union in 2018, 27,838 were female, by far the fastest growing sector of the game, with a 14.6 per cent increase over 2017 (an additional 3500 players). By contrast there was a 4.8 per cent drop in male players, especially in the crucial 13–20 years age bracket. See: http://www.allblacks.com/News/33093/female-rugby-player-numbers-continue-to-grow and http://www.nzrugby.co.nz/

[26] See https://www.warriors.kiwi/news/2018/08/01/vodafone-warriors-unveil-nrl-womens-premiership-squad/

[27] Annual Report, 2017, Available from: http://www.nzfootball.co.nz/asset/downloadasset?id=51c5d5e5-f5e2-43c6-90c7-b0d194d51cac

[28] The number 261 was worn by Kathrine Switzer when she became the first woman to officially enter and complete the Boston Marathon (previously run only by men).

Unpublished sources

Barclay, Jenny, 'An Analysis of Trends in New Zealand Sport from 1840 to 1900', BA(hons) research essay, Massey University, 1977

Hall, Fiona J., '"The Greater Game": Sport and Society in Christchurch During the First World War, 1914-1918', MA thesis, University of Canterbury, 1989

Hammer, M.A.E., '"Something Else in the World to Live For": Sport and the Physical Emancipation of Women and Girls in Auckland 1880-1920', MA thesis, University of Auckland, 1990

Kuitert, V., 'Ellen Melville 1882-1946', MA research essay, University of Auckland, 1986

Ryan, Geraldine, '"Muscular Maidens": The Development of Sport and Exercise in Girls' Schools in New Zealand', MA long essay, University of Canterbury, 1983

Simpson, Clare S., 'The Social History of the Christchurch Young Women's Christian Association, 1883-1930', MA thesis, University of Canterbury, 1984

Stothart, R., 'The Education of New Zealand Recreation Workers', MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 1977

Upton, B. Susan, ‘Women in the Club: Women’s clubs in the Wellington region, 1895-1945’, MA thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 1993

YWCA scrapbooks, South Canterbury Museum, Timaru

YWCA scrapbooks, Auckland Institute and Museum

YWCA scrapbooks, Canterbury Public Library

Wellington Women's Club records, ATL

Published sources

Anderson, Atholl, Judith Binney and Aroha Harris, Tangata whenua: an illustrated history, BWB, Wellington, 2014

Coney, Sandra, 'Amazons of the Sea', Broadsheet, April 1985, pp. 14–19

Fletcher, Sheila, Women first: the female tradition in English physical education 1880–1980, Athlone Press, London, 1984

Fry, Ruth, '"Don't Let Down the Side": Physical Education in the Curriculum for New Zealand Schoolgirls, 1900–1945', in Brookes, Macdonald and Tennant (eds), 1986, pp. 101–17

Great Kiwi sportswomen address and birthday book, Hillary Commission, Wellington, 1991

Haig, Shirley and Pamela Barnert, 'The Sportswomen', in Canterbury women since 1893, Regional Women's Decade Committee, Christchurch, 1979, pp. 22–36

Harding, Brenda J., Women in their time: seventy-five years of the Otago Women's Club 1914–1989, Otago Women's Club, Dunedin, 1990

Ingram, N.A., A factual history of surf life-saving in New Zealand 1910–1952, Hurt Printing and Publishing Works, Lower Hurt, 1953

King, Helen, 'The Sexual Politics of Sport: An Australian Perspective', in Richard Cashman and Michael McKernan (eds), Sport in history, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1979

Macdonald, Charlotte, ‘Moving in Unison, Dressing in Uniform: Stepping Out in Style with Marching Teams’, Bronwyn Labrum, Fiona McKergow and Stephanie Gibson (eds), Looking flash: clothing in Aotearoa New Zealand, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2007, pp. 186–205

Macdonald, Charlotte, ‘Ways of Belonging: Sporting Spaces in New Zealand History’, Giselle Byrnes (ed), The new Oxford history of New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 269–96

Macdonald, Charlotte, Strong, beautiful and modern: national fitness in Britain, New Zealand, Australia and Canada, 1935–1960, BWB, Wellington, 2011

McCrone, Kathleen E., Sport and the physical emancipation of English women 1870–1914, Routledge, London, 1988

Mangan, J.A. and Roberta J. Park (eds), From 'fair sex' to feminism: sport and the socialization of women in the industrial and post-industrial eras, Frank Cass, London, 1987

New Zealand Sportswoman, April-November 1949

New Zealand Sportswoman, 1991–1992

Obel, Camilla, Toni Bruce and Shona Thompson (eds), Outstanding: research about sport and women in New Zealand, Wilf Malcolm Institution of Educational Research, Hamilton, 2008

Quirk, Carol, The first patrol: a history of the Lyall Bay Surf Lifesaving Club 1910-1985, The Club, Wellington, 1985

Ryan, Greg and Geoff Watson, Sport and the New Zealanders: a history, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2018

Simons, Dorothy, New Zealand's champion sportswomen, Moa Publications, Auckland, 1982

Simpson, Clare and Lisa Hayes (comps), Herstory diary: the New Zealand women's diary 1989, New Women's Press, Auckland, 1988

Simpson, Clare, Women and recreation in Aotearoa/New Zealand: an annotated bibliography, Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism, Lincoln University, 1991

Stothart, Robert A., The development of physical education in New Zealand, Heinemann, Auckland, 1974

Waring, Marilyn, 'The Games People Play', NZ Listener, 25 August 1984, p. 24

Women and recreation, New Zealand Council for Recreation and Sport, Wellington, 1981

Women in sport, February 1948 – February 1949