Rural Women New Zealand

1925 –

Theme: Rural

Known as:

- Women’s Division Farmers’ Union

1925 – 1945 - Women’s Division Federated Farmers

1945 – 1998 - Rural Women New Zealand

1999 –

This essay written by Rosemarie Smith was first published in Women Together: a History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Rosemarie Smith in 2018.

1925–1993

In 1925, at a tea-party in Wellington for wives of delegates to a Farmers' Union (FU) meeting, sixteen women agreed on the need for their own organisation. They responded to an account given by Florence Poison, who had accompanied her husband on an FU recruiting drive in the North Island, of 'the restricted, bare, lonely lives of [farm] women working long hours with few household amenities and their need for contact with others'. [1] The inaugural meeting of the Women's Division of the New Zealand Farmers' Union (WDFU) was held the following morning, 28 July 1925.

The sixteen women formed an immediate nation-wide network of capable and motivated organisers, ideally placed to set up an organisation for farm women. They came from relatively well-established farms and therefore had financial backing and comparative leisure; their husbands encouraged them, and provided a model for political activism. Local branches of the FU were not always as enthusiastic, but the national executive gave £50 and access to the membership address list. Ambitious projects were thus able to be initiated even before there was a solid infrastructure of local branches.

Evidence suggests that the men were mostly concerned with mustering support for their own political agenda, and support for the FU was made the first aim of the new organisation. But the second aim, the welfare of rural women and children, was the central concern of the 2000 handwritten letters which secretary Mabel Jackson sent out to FU wives during the first year to recruit members, and of the letters in reply. The women wanted immediate remedies to their problems, and saw the WDFU as a direct means of self-help.

These expectations were expressed in sixteen wide-ranging aims which sought improvements in living conditions and rural services, especially medical and nursing facilities, domestic help, restrooms, schools, agricultural labour relations, and home science education for rural women. They also included the study of social questions, keeping an eye on legislation, overseeing the welfare of young rural migrants from Britain, fostering community spirit, and generally promoting the welfare of 'Home, Country and Empire'. [2]

These aims became the basis of the WDFU programme for nearly 70 years, with gains in some areas such as education and health services having to be constantly defended. In 1985 the aims were condensed to three clauses: conditions for rural women and children took priority over support for Federated Farmers, although a statement emphasising the importance of co-operation between men and women was retained.

The WDFU adopted the FU motto – 'Principles Not Party' – and a non-partisan stance, although the founders were conscious of their political power. The strongly worded WDFU pamphlet 'The Women Organise' (1929) emphasised a woman's partnership with her husband in farming: 'A WOMAN'S VOTE IS EQUAL TO A MAN'S and is therefore worth organising.' [3] Membership of the WDFU was initially restricted to the wives, sisters and daughters of landowners, but was later opened up to all rural women.

The first national conference, held in 1926, was attended by 32 of the 100 financial members. A constitution was introduced, aims accepted, and a national executive elected. It was decided to form as many branches as possible, each with a minimum of five members; the first was Oakura in Taranaki, formed in June 1926. A year later membership had reached 1250, and it doubled again in 1928. By the Silver Jubilee in 1950, there were 25,000 members, 650 branches, and 40 provincial executives.

One of the first priorities of the fledgling organisation was to provide affordable home help for mothers suffering from ill health or overwork, or at childbirth. In its day this scheme was probably as significant as the women's refuge movement in the 1970s, in that the well-being of women in the home became a matter for public discussion and intervention. In 1929 Dominion secretary Una Macleod caused a stir with her comment to Robin Hyde, published in the Wanganui Chronicle: 'If there were legislation passed compelling every farmer to keep his wife as decently as he has to keep his cattle, perhaps the maternal mortality wouldn't be so heavy amongst country women.' [4]

In April 1927 the WDFU placed newspaper advertisements for 'housekeeper, willing to do anything' and 'bush nurse, with surgical and midwifery certificates'. [5] The bush nurse scheme was based on an Australian model, but the housekeeping scheme was a local innovation. The women appointed were available for temporary employment by any rural woman, and the WDFU assured access by establishing a 'community chest' to subsidise wages; users of the service paid what they could afford.

The schemes were enormously popular – in one year in the early 1930s housekeepers attended 1100 homes – but were limited by the lack of suitable staff. To offset this, the WDFU raised funds to establish rest homes where rural women could have a holiday and recuperate, usually for one month. It was proudly asserted that the only rule for guests was breakfast in bed. By the 1960s the larger rest homes were no longer economically viable and were gradually sold off, and the funds invested in a trust for charitable projects. A few smaller ones remained as holiday cottages. The bush nurses were later incorporated into the state district nursing service. The housekeeping scheme endured, with a state subsidy from 1946, and by 1993 it was known as 'Homecare'.

Intensive fundraising at branch and national levels resulted over the years in the endowment of a vast range of philanthropic projects, from buildings, equipment and furnishings for local organisations to major funding for health research ($73,000 for the Golden Jubilee projects alone). One early fundraiser, The New Zealand Household Guide (1929), provided a fascinating glimpse of the diet and domestic work of the day.

Educational activities soon became part of all branch programmes, with talks, demonstrations, workshops and special projects being slotted into regular meetings or run as separate courses. Most emphasised domestic crafts, but also personal development, leadership and organisational skills. Many were arranged in conjunction with the adult education providers of the day and, after 1937, with the Women's Institutes.

Communication with members was assisted in the early years by the farming newspapers, especially the New Zealand Dairy Exporter, until the launch in 1933 of the organisation's own newsletter, New Zealand Countrywoman, which survived periods of varying fortune.

One WDFU aim was to establish a 'vigilant watch on all legislative measures brought before parliament and ... protest against any ... as are deemed injurious to women's interests'. [6] The women learned to use the political system to further their aims, acquiring skills and contacts through their informal association with the FU. In 1946 they followed the FU in repudiating any nominal association with trade unions, becoming the Women's Division Federated Farmers (WDFF). Although the subsidiary position implied by the name was always been viewed as a liability by some members, attempts to change it further were resisted.

The annual conference continued to be the governing body of the organisation; until 1985 a cumbersome remit process inhibited action until it was endorsed by conference. Considerable power was, however, delegated to the Dominion executive, whose members had specific areas of responsibility: education, legislation, health, environment, and rural services. The organisation made regular submissions to government in all these areas.

The national office in Wellington had paid staff from 1928, and in 1993 employed three people. It provided accommodation for visiting members at its 'Honda' clubrooms. [8] But its resources remained very modest compared to those of Federated Farmers. [9]

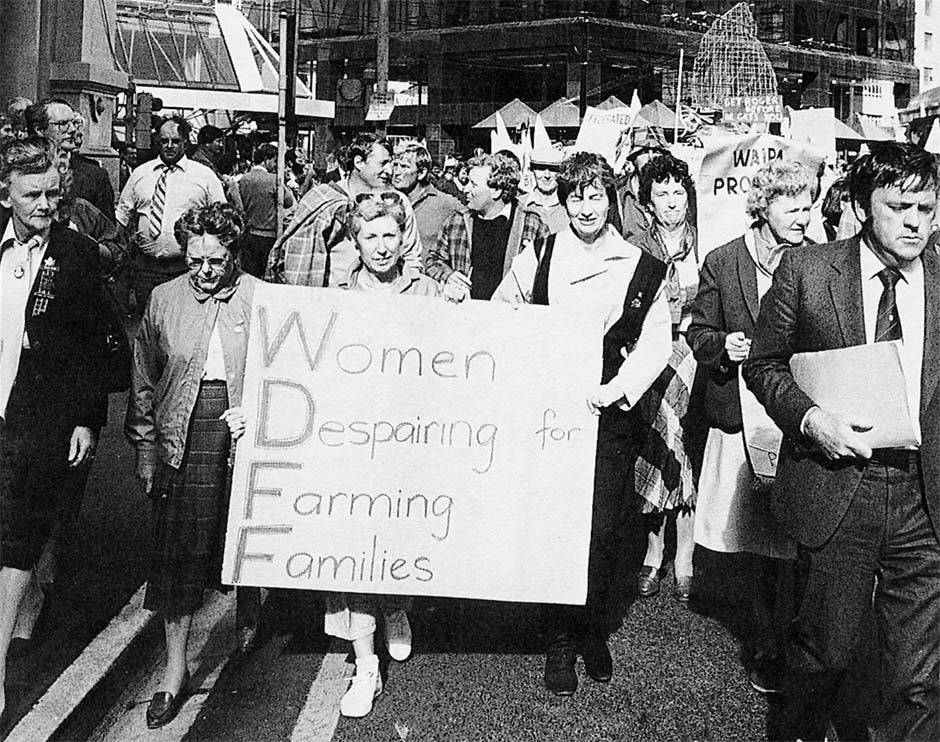

Tony Kellaway photo / Women’s Division Federated Farmers.

Members of the Women's Division Federated Farmers participate in a march to raise public awareness of the economic plight of rural communities, Wellington, 1986.

The 1980s brought change and challenges to the rural community. Many families faced financial crisis, there was a revival of early concerns about rural services, and environmental issues such as sustainable land use took on new dimensions. WDFF membership was declining and ageing; many members no longer had the energy (or the skills) to cope with the pace of change, but valued the organisation as a source of support and companionship. Alternative groups with more flexible structures were attracting public attention as the representatives of rural women.

A controversial report commissioned from the New Zealand Futures Trust in 1985 challenged the WDFF to reassess its identity, direction and strategies. One outcome was to secure corporate sponsorship for leadership courses and community development work, including a programme of Personal Development Seminars. These contained modules on health, education, central government and administration, lobbying, Treaty of Waitangi issues, and resource management, the aim being to empower members and to strengthen rural communities.

Membership in 1992 was down to 7022 in 410 branches, but an energetic core was reasserting women's role in agricultural production, and demanding that it be recognised by Federated Farmers, agribusiness, education institutions, and the state. These new goals were being achieved without sacrificing the long-standing WDFF tradition of women enjoying each other's company over the tea and scones.

Rosemarie Smith

1994–2018

The 1999 change of name to Rural Women New Zealand (RWNZ) finally removed any implication of a subordinate relationship within the mostly male Federated Farmers. The organisation also streamlined its own structure, and sharpened its focus and public relations capability. By 2018 it had built on its legacy, particularly from the years of rapid change and structural reform so apparent in 1993, and honed its advocacy, leadership and training skills on behalf of the rural community. Despite a drastic decrease in membership, president Fiona Gower reported that RWNZ continued to attract a core of committed, increasingly diverse and very able women who were passionate about its work. Although more members were independent, rather than belonging to a branch, opportunities to meet face-to-face continued to be vitally important. [10]

RWNZ aimed to be ‘the trusted authoritative voice on rural community issues’; and to ensure that the wellbeing of rural communities would be considered in all policy and legislative development. [11] In the year to August 2018, for example, parliamentary submissions covered rural environment, health, business, technology, education and social issues, as well as some areas, such as taxation reform, which had once been left to Federated Farmers.

RWNZ also spoke out strongly on inequitable access to broadband and mobile phone services in rural areas, and how severely this impacted on rural communities, especially as business, education and government services all increasingly moved online. Health issues continued to be a major focus, especially mental health. This was reflected in the 2013 survey ‘Feeling Rotten’, which revealed unhealthy levels of stress and depression. There was also ongoing involvement in the Rural Support Trusts established in the 1980s. [12]

The ‘tea and scones’ aspect of RWNZ’s community work was still visible, most spectacularly in the way it took on the catering for the ‘Farmy-Army’ that helped clean up the liquefaction mess caused by the Christchurch earthquake in 2011. [13] The cleverly named ‘Aftersocks’ merino socks fundraiser was both a sympathetic acknowledgement of the stresses of earthquake aftershocks, and a means to stock up the Adverse Events Fund, which provided assistance after disruptive natural events such as flood, drought and fire. [14] Country women’s famed catering skills were also evident in a new batch of recipe books published in 2010–14. However, this traditional women’s group staple was transformed by professional publication into handsomely produced books which became national best sellers. [15]

Astute asset management and charitable trust status provided an enviably solid base for RWNZ’s work, and its 2016 Charities Commission return recorded $2.5 million as charitable ‘giving back’. Much of this was targeted funding, such as the seeding grants for rural primary school fruit and vege gardens initiated in 2012. [16] A significant slice of its base funds came from the $18m sale in 2014 of Access Homehealth, by then a leading home care provider, which had originated in the venerable WDFU bush nurse and housekeeping schemes begun in the 1920s. [17] Several regions also had their own trusts.

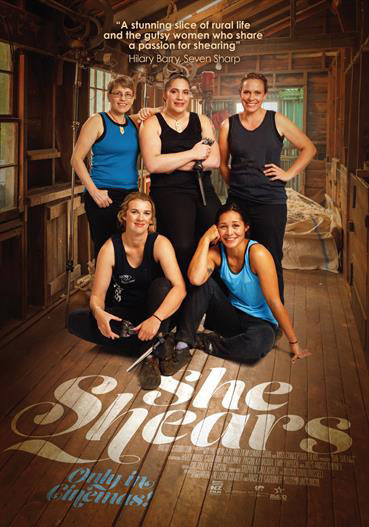

National awards such as RWNZ Business Awards (formerly Enterprising Rural Women Awards) both promoted the recipients and celebrated the diversity of women’s rural community roles. Awards went to a boutique winemaker in 2017 and a specialist horticulturalist in 2018. Sponsorship of the movie ‘She Shears’ (2018), celebrating women shearers, had a similar purpose. National Board Chair Penny Mudford explained:

[I]t is important to shine a light on the women who live and work in rural New Zealand, often invisibly. Women work hard. They are talented and skilled at what they do and for rural, this is in dairy sheds, growing sheds, sorting and packing sheds, garden sheds, and woolsheds. The film is an honest depiction of strong and capable women who are iconic role models for other women and girls. [18]

Miss Conception Films.

She Shears (2018), a documentary about New Zealand women shearers Jills Angus Burney, Hazel Wood, Catherine Mullooly, Pagan Karauria and Emily Welch, had its world premiere at the 2019 New Zealand International Film Festival. Presented by Miss Conception Films, a group focusing on female-led stories, it was made with funding support from Rural Women New Zealand.

RWNZ had also continued the WDFF’s international advocacy role, as explained by Fiona Gower after attending the UN Status of Women 62nd session in New York 2018, where she also represented Pacific Women’s Watch. The issues relating to eliminating discrimination against women were global: ‘We talk of isolation, talk about lack of services – education and health, food security and land security and, of course, violence against women and children is a huge thing right around the world.’ And as far as New Zealand was concerned, ‘even though we've had 125 years of suffrage, we're still not there yet’. [19]

Rosemarie Smith

Notes

[1] Luxton, 1985, p. 14.

[2] And So We Grew, title page.

[3] F.I. Preston papers.

[4] Robyn Hyde, 'Women of the Wayback', Wanganui Chronicle, 4 May 1929.

[5] And So We Grew, p. 225. Nurse Blackie and Miss Wishaw were the first employees. By the end of 1927, nine housekeepers were employed.

[6] Luxton, 1985, p. 18.

[7] Major WDFF campaigns included those for eradication of hydatids and leptospirosis, and for compulsory safety frames on tractors.

[8] ‘Honda’ was the name of Dr Agnes Bennett’s Lowry Bay home, which she bequeathed to WDFF in 1947 as a rest home. Proceeds from its eventual sale were used to buy the ‘Honda’ clubrooms in central Wellington.

[9] In 1992 the WDFF had assets worth $853,000 and an annual turnover of $250,000; FF had $4.5 million in assets and a $3 million turnover.

[10] RWNZ president Fiona Gower, personal communication, 2018

[11] https://www.ruralwomen.org.nz/index.html

[12] 3News, ‘Rural women depressed, anxious’, Newshub, 22 March 2013: https://www.newshub.co.nz/nznews/rural-women-depressed-anxious-2013032308

[13] RWNZ website, ‘Cooking Up a Storm to feed the Farmy Army’, 3 August 2011. See https://www.ruralwomen.org.nz/news-and-inspiration/cooking-up-a-storm-to-feed-the-farmy-army

[14] RWNZ website, ‘Aftersocks’. See https://ruralwomennz.nz/aftersocks/

[15] Rural Women New Zealand, A Good Spread: Classics from the Recipe Books of Rural NZ Women, Random House New Zealand, Auckland, 2010; A Good Harvest: Recipes from the Gardens of Rural Women New Zealand, Random House New Zealand, Auckland, 2012; A Good Baking Day, Random House New Zealand, Auckland, 2014.

[16] RWNZ website, ‘Fruit and Vege Garden Grants for Primary Schools’, 30 August 2012. See https://www.ruralwomen.org.nz/news-and-inspiration/garden_grants

[17] RWNZ website, ‘Sale of Access Homehealth – A New Chapter’, 19 November 2014. See https://www.ruralwomen.org.nz/news-and-inspiration/sale-of-access-homehealth-a-new-chapter

[18] RWNZ website, ‘She Shears Premieres in Masterton’, 11 October 2018. See https://www.ruralwomen.org.nz/news-and-inspiration/she-shears-premieres-in-masterton

[19] ‘Struggle for equality not done yet’, Otago Daily Times, 22 August 2018.

Unpublished sources

F.I. Preston papers, Hocken

Gower, Fiona, ‘Rural Women New Zealand: Strengthening Rural Communities’, Kellogg Rural Leaders Programme Project, 2009

Rural Women New Zealand records, 1999–2018, held by Rural Women New Zealand, Wellington

Smith, Rosemarie, interviews with Jo Gravitt, executive officer, WDFF, 1992; Isla McRae, past president, WDFF, 1992

Women’s Division Federated Farmers collection, c. 1925–1983, ATL

Women’s Division Federated Farmers records, 1984?–1999, held by Rural Women New Zealand, Wellington

Published sources

And So We Grew: The Story of the Women's Division of the Federated Farmers of New Zealand I925–1950, Dominion Headquarters WDFF, Wellington, 1950

Express (Rural Women New Zealand), 2015–

Luxton, T., In Community of Spirit: A History of the Federated Farmers of New Zealand Women's Division, 1925–1985, Lindon Publishing, Auckland, 1985

New Zealand Countrywoman, 1933–1991 (thereafter renamed Rural Woman)

Rural Woman, 1991–2008

Rural Women Outlook, 2011–2013

Women's Division of the Farmers' Union, '17 Reasons Why You Are Asked To Join', c. 1927

Women's Division of the Farmers' Union, 'The Women Organise', c. 1929

Community contributions