This essay written by Anne Else was first published in Women together: a history of women's organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Anne Else in 2019.

All-women arts and crafts groups have a long history in this country. In Māori society, where women and men for the most part undertook different branches of the arts and crafts, group work was the norm – though named individuals were often singled out for their particular gifts or skills. After the arrival of the Pākehā, writing, the 'fine arts' and the crafts formed three linked strands in New Zealand's cultural life. For several decades, the history of women acting together in these fields was mainly one of small, informal associations, often taking shape around a course or teacher. Some of these groups, notably in the crafts, eventually came together under the umbrella of a national federation. Others dispersed as members moved on to independent work, or their broader political aims appeared to have been largely achieved.

From the nineteenth century to the 1920s, groups of women interested in writing and literature arranged to meet regularly; probably painters and craftworkers did too, though less evidence of their meetings remains. Between the wars, one notable group – The Group – was formed by women painters, and women remained the majority of its most active members. Hundreds of women worked in informal art, craft and literary 'circles' within other organisations, for example the Women's Institutes and women's club networks; writers, readers and journalists joined larger organisations with widespread branches; and the first craft organisation to reach out nationally began. All these groups were innovative, in that they offered to a wide variety of women a space and context within which to pursue a chosen occupation beyond marriage and motherhood or the demands of a bread-and-butter job. The Group had the most acknowledged influence within its own field, overtly challenging the conservative art establishment. The craftswomen were eloquent advocates for the aesthetic as well as the practical value of their work. The writers' groups promoted women's books and nurtured women who would later become important figures.

After the Second World War, new growth came from increasing affluence, a more enlightened school curriculum and more contact with overseas developments, combined with married women's eagerness to move beyond the confines of suburban domesticity. Spinning and weaving, practised almost entirely by women, and pottery, pioneered by women, were particularly prominent. In the 1950s the foundations were laid in the crafts for effective national organisations. Their determined, patient work did much to broaden the scope and raise the status of those crafts most closely associated with women and domesticity.

But as yet, none of these groups sought publicly to question or overturn the basic tenets of 'the arts' in twentieth-century European culture: that individuals produced bodies of work for experts to judge, using objective, universal, purely aesthetic criteria; and that though the hierarchy of merit might alter over time, characteristics such as gender, race or class were irrelevant.

By the late 1970s, feminist arts groups were profoundly challenging all these premises. They were also organising a huge variety of 'woman-centred' projects, events and publications, demonstrating 'the drastic shift in perspective which can only occur in the context of explicit feminism, after considerable open anger, and with the backing of feminist solidarity'. [1] Their work reached large numbers of women who might not have been to an art gallery or a poetry reading before, and brought a range of responses from dominant figures and institutions within the arts world.

Hocken Collections, 0131_01_001A

Painting students at Elam School of Art, c. 1897. Back from left: unknown, Louise Laurent, Margaret Woodward (later Jackson), Jane Eyre, Alice Falwell (later Whyte), unknown. Front from left: Edward Payton, Amy Rhodes (later Smythe), unknown.

Organising the arts

In the late nineteenth century, women-only organisations were a familiar feature of the European and colonial arts world beyond New Zealand. The Society of Female Artists was founded in England in 1857 (later changing its name several times); the Society of Women Writers and Journalists began in London in 1894. Many similar organisations formed in various European cities in the second half of the nineteenth century, as well as in the USA, Canada, and Australia. Their broad aim was to counter the 'restrictive practices imposed by professional bodies and … institutions' – including the extremely influential all-male clubs – which 'jealously guarded privilege and worked to the exclusion of women'. [2] They provided alternative networks and opportunities to bring women's work to public notice, seeking to enlarge women's place within the male-dominated arts world, rather than to challenge and change that world. New Zealand women studying and working abroad in the arts made good use of the existing women's organisations. Writers might contact the New Zealand Circle of the London Lyceum Club, warmly recommended by novelist Edith Searle Grossmann in 1904; painters might join the Society of Women Artists, or the Women's International Art Club, founded in London in 1900. [3]

No women artists' or writers' societies of similar scale and formality began in New Zealand until the 1930s, partly because they did not seem to be necessary. In the later nineteenth and early twentieth century, committed New Zealand painters and writers were mainly independent entrepreneurs, promoting their work and reputation as best they could in a difficult, albeit improving, market and environment. In fine arts, the additional obstacles facing women related mainly to overarching gender roles and prescriptions. In 1885, when Nelson artist Emily Cumming Harris went to a meeting for intending exhibitors at the forthcoming Indian and Colonial Exhibition in London, it was the first public meeting she had ever attended, and the first time women had been present at such an occasion – despite their strong showing at exhibitions. Married and single women alike found that domestic and family responsibilities left little time for the arts. Successfully combining a painting career with marriage and motherhood remained exceptional until at least the 1940s.

However, the structure of the arts world here was still uncomplicated and relatively free from institutional or ideological barriers based on gender. High culture in general, and the fine arts in particular, were seen as morally and spiritually elevating, and hence more closely associated with the feminine than with the masculine. The professional art training courses which began here in the 1870s, including life drawing, were fully open to women, who found like-minded colleagues and friends there. By the late 1880s, women comprised nearly half the working members of the influential art societies. Prominent women artists such as Margaret Stoddart, Mary Elizabeth Richardson Tripe and Dorothy Kate Richmond were elected to art society councils (though not to the most senior positions) and served on selection committees. But for the most part, women played the familiar supportive role: they were 'usually responsible for social activities and helped with fundraising'. [4]

Women also joined the working artists' clubs which sprang up from the 1880s, for example Christchurch's Palette Club, begun in 1889 because of dissatisfaction with the Canterbury Society of Arts, or the first Wellington Art Club, founded in 1892. Its successor, formed in 1911, was less egalitarian: women paid half the male subscription rate, but could not be elected to the General Committee.

Writing attracted far more women than painting, partly because it required no specific training, outlay, space or equipment. But though some women did train alongside men in the journalism courses which began to be offered by university colleges from 1909, they were barred from many jobs in journalism. Women writers venturing beyond the safe categories of romance and children's stories were wise to use ambiguous pseudonyms, as Edith Lyttelton ('G.B. Lancaster') did.

Small local reading and writing groups formed early, some offering publication in their own magazines. Most seemed to have targeted mainly younger single women keen to occupy their minds and time with something more challenging than the usual domestic and social round. Members of the Rata Club, begun in Christchurch in 1897, adopted Māori pseudonyms and met for literary 'runanga'; the average attendance was five. Their magazine, Rata Leaves, had reached Volume 5 by 1900. Auckland's Atom Quarterly, the journal of the Atom Club, which held literary 'At Homes', was 'open to receive MSS from any girl contributor, providing she resides in New Zealand, is unmarried and a subscriber'. [5] It promoted fundraising for Queen Victoria Māori Girls' School, and its contributors included children's writer Isabel Maude Peacocke, and feminists Jessie Mackay and Wilhelmina Sherriff Bain.

For writing men, the common meeting ground was the pub; but for women, finding respectable places to meet outside private homes was a recurring problem well into the 1920s. In the more restricted environment of Britain, it had been one of the main factors spurring the formation of the London Lyceum Club, which provided 'a suitable meeting place for writers, artists and other freelance workers who needed to meet male colleagues and agents without compromising themselves'. [6] In New Zealand, Blanche Baughan, Jessie Mackay and Mary Colborne-Veel began the Canterbury Women's Club in 1913, to provide premises and occasions where women who were interested in literature and the arts could gather.

The number of women declaring themselves to be professional writers rose from less than 8 percent to just over 12 percent of the total numbers in this category between 1916 and 1936. Women were slowly gaining ground in a growing but still very small field. In addition, large numbers were writing in their spare time. The number of women professionally identifying as some kind of artist (other than 'commercial artist') in 1936 was almost exactly the same as the number of women writers, but women artists formed a clear majority (over 60 percent) of all those in their field.

In 1927, a group of five ex-students of Canterbury University College School of Art – Evelyn Polson (later Page), Viola Macmillan Brown, Margaret Anderson (later Frankel), Ngaio Marsh, and Edith Wall – met to establish The Group. The usual explanation is that like its later counterparts – the Rutland Group in Auckland, the Independent in Dunedin – The Group 'began in response to perceived deficiencies in art institutions, especially art societies, which were regarded as bastions of conservatism'. [7] Janet Paul, who in 1980 published a detailed examination of how women artists had fared in New Zealand, notes that its founders also needed a means of getting away regularly from their home environments, which were not conducive to steady, serious work. They were at least second generation New Zealanders, had a little money and some education, and were conscious of a history of being in New Zealand. By the late 1920s they could envisage remaining here to pursue a career as an artist. At first they rented a tiny room near the School of Art; when they moved to a bigger studio, they invited, in Evelyn Page's words, 'the newest, the most modern of our contemporaries' – including men – to join them. [8] However, women (including Rita Angus) predominated among the most regular and longstanding exhibitors.

The Group's success and longevity were partly due to the fact that it 'functioned with the minimum of organisation and contact between members, its chief activity being the mounting of exhibitions'. [9] Contrary to art society practice, each member or invited artist was free to select his or her own works for exhibition, and each artist's work was hung together, so that it could be seen as a whole. The members shared the cost of exhibitions. This successful format remained unchanged till The Group's last show in 1977; the feminist groups which were beginning around that time used a very similar one.

Gore Historical Museum

Members of the Gore Girls' Literary Club, c. 1909. Club members met to present papers on a variety of literary themes. Edith Howes, writer of children's books, is seated middle row, third from right.

Women writers were differently situated. In a 1936 article for Woman To-Day, Robin Hyde (Iris Wilkinson) divided them into the hobbyists, who formed and joined clubs, and preferred talking about writing to doing it; the journalists, who were underpaid and not given enough scope; and the 'serious writers', driven to 'express some inward revelation of feeling so urgent that it counts for more than anything else in life'. [10] The 'clubs' by then included the literary circles of the Lyceum and similar women's clubs; the Penwomen's Club, founded in Auckland in 1925 as the League of New Zealand Penwomen (after the League of American Penwomen) by Texas-born Edna Graham Macky; and the New Zealand Women Writers' Society (NZWWS), which began in 1932 in Wellington.

In reality, women moved among all three of Hyde's categories, and joined or left the clubs, as their lives altered. Club programmes constituted a form of continuing education for 'bookish' women who would otherwise have had little or no access to it, and also promoted women's writing. Between 1928 and 1945, for example, the poetry section of the Otago Women's Club offered a full literary programme, including discussions of New Zealand women poets, an 'intensive study' of Elizabeth Barret Browning's feminist epic Aurora Leigh, and a 'brilliant resume of New Zealand literature' by the guest speaker – Robin Hyde. [11]

In the 1920s, as Dennis McEldowney points out, 'most of the influential figures on the literary scene were journalists. So were many of the practising writers ... poetry, fiction, criticism and history were what journalists did in their spare time and their more reflective moments’. Many of the founding members of the NZWWS were or became working journalists, though not until World War II did more than a handful manage (at least temporarily) to break out of the confines of the women's and children's pages into general reporting and feature writing. But just as the society was forming in 1932, an important shift was taking place. 'Although the links between journalism and literature were never entirely broken, increasingly from the 1930s literary activities were in the hands of academics, or people with academic connections and inclinations.' [12] For decades, this group included very few women.

Those working beyond such circles, including most women writers, became increasingly marginalised from the body of work emerging as ‘New Zealand literature’. The records of the women writers' organisations suggest that from the 1940s to the late 1960s, the majority of members thought of 'New Zealand literature' as something being written elsewhere, principally by men – some of whom they invited to lecture to them – rather than something they themselves could take part in producing. Like some women painters, such as Flora Scales, many seem to have regarded themselves as perpetual students, never fully-fledged practitioners. However, a small number did not share this limiting view. They valued the societies as a sanctioned, safe, supportive way of exposing (or re-introducing) their writing to public scrutiny, or simply as the only available form of contact with other writers. They would later make their mark in the more receptive climate of the 1970s and 1980s.

While women painters formed no such formally structured, women-only organisations, in the 1950s small groups of women, often art school graduates, began meeting regularly in order to continue painting and drawing while primarily occupied with families, homes and other employment. In particular they sought life drawing. In Auckland, a group held in Nan McGregor's home included Louise Henderson; in Hamilton, from 1947 to 1965, Margot Philip, Jean Fairburn, Heather Lomas, Janet Paul and others met; in Wellington, from the late 1940s, Helen Crabb ('Barc') encouraged married mothers to continue their work at the daytime life drawing classes she held in her old house in Hobson Street. Some of these painters would later support the feminist arts groups of the 1970s and 1980s, welcoming their outspoken, public expression of what the older women had long privately believed about the obstacles facing women artists.

Craft organising

As Germaine Greer pointed out in 1979, by far the greater proportion of female creative power in the visual arts 'was never expressed in painting but in the so-called minor arts'. [13] At least 20 Art and Industry exhibitions were held in New Zealand before 1900, modelled on similar exhibitions overseas. Apart from painting, women's work was, with few exceptions, confined to the 'Ladies' Work' and 'Home Industries' sections. It included painted furniture, fans, embroidery, knitting, lace, crochet, ribbonwork, tapestry, small woven items, shellwork, fernwork, and pressed flower work. A similar range was sold at charity bazaars. These 'feminine' crafts were not considered to be in the same category as the fine arts. Mostly home-taught, they required very little space or financial outlay; however, they consumed huge amounts of women's time (and were therefore not a viable way to earn money). They were essentially seen as appropriately genteel (but innately trivial) leisure occupations for affluent middle class ladies.

Nelson Provincial Museum

Stall at a Wesleyan church bazaar, Nelson, 1884. Women made a wide variety of handcrafted items for fundraising purposes, often incorporating commercial laces and trimmings.

In the 1900s, the growth of the technical schools, the advent of the free place system, and the arrival of new teachers fresh from Arts and Crafts instruction in England rapidly extended the craft training available in New Zealand, notably at the technical institutes and art schools in the main centres. The courses on offer included metalwork, enamelling, jewellery making, leatherwork, woodcarving, bookbinding, 'art embroidery' and weaving. Women flocked to enrol, both for their own interest and as a possible means of earning a living. Such crafts became part of the art society exhibiting circuit. Casual classes were popular too: by 1918, for example, Otago Women's Club members were 'assiduous in practice and experiment with the new ideas'. [14] The central paradox of the Arts and Crafts revival was evident here, as elsewhere: though the overall intention might be to bring good design and handwork to the masses, it was only the relatively well-to-do who could afford to buy such items, or to make them.

Alexander Turnbull Library, EP-0237-1/2-G.

Elizabeth (Bessie) Jerome Spencer gives a spinning demonstration at a Women’s Institute gathering in the 1930s.

Nevertheless, some craftswomen did make a commercial success of selling and teaching. In 1927, sisters Josephine and Sybil Mulvany enrolled in the London School of Weaving. Returning to Auckland with a spinning wheel, looms, and 'quantities of weaving materials', they opened a shop, Taniko Weavers, and a workroom. [15] Their pupils included Florence Akins, who later became an influential teacher. They made fabrics and table linen, working mainly in silk, linen and cotton. Other enthusiasts helped to spread interest and skill. Bessie Jerome Spencer, who founded the Women's Institutes here in 1921, was a keen advocate of handcrafts, particularly spinning and weaving. Her closest friend was the important pioneer of plant dyes, Amy Hutchinson. [16]

By 1933 the Arts and Crafts Circle of the Auckland Lyceum Club could invite 15 professional craftswomen, including self-taught studio potter Briar Gardner and weaver Sybil Mulvany, to mount an exhibition of work at the clubrooms. The next year, potter Olive Jones returned from training in England and was soon earning a modest living. In 1935 what seems to have been the first national women's craft organisation here, the New Zealand Guild of Spinners, Weavers, and Dyers, was proposed by Dr Mary Barkas of Thames (also a Women's Institute member), Miss Lewis of Titirangi and Miss Buchanan of Christchurch; by 1937 it had 52 members, and was holding summer schools and displays as well as running courses. That year the Dominion ran an article misleadingly headed 'Arts and Crafts At Home – What Some City Women Do With Their Spare Time'. Several of the women it described were professional craftworkers, including jeweller Edith Morris, weaver Erica Admore, and Brenda Doyes, who worked in pewter and brass and was 'enthusiastic about Māori designs'. [17]

Most of this varied craft activity seems to have died away before World War II, leaving the field to pottery and fibrecrafts. This is partly explained by a shift in fashion away from the curved lines and rounded forms of Art Nouveau to the precise geometry of Art Deco, strongly associated with commercial manufacture, followed by the austerity and shortages of wartime; but it also reflected a loss of prestige for the crafts in general. By 1947, Canterbury's School of Art had shifted most of its craft courses to the technical school – except for Florence Akins' weaving course, which started that year with one student, and grew steadily more popular.

Though large numbers of women learnt to spin during the Second World War, by 1945 many never wanted to see a wheel again, and only a dedicated few continued. But other forces were at work promoting experience of, and eventually markets for, fine arts and crafts. When Dr Clarence Beeby became Director of Education in 1940, he found art and craft teaching in schools in a 'distressing state'. The shortage of materials and hidebound approach had led to what he called 'the making of rubbish out of rubbish'. [18] With inspiration going back to the New Education Fellowship Conference of 1937, notably the work of English educator Susan Isaacs, and with Peter Fraser's support, he set about ensuring that virtually all schoolchildren were introduced to weaving and pottery, as well as to a much more creative art curriculum. In 1942 Doreen Blumhardt was employed as National Adviser in Art and Craft; over the next six years she inspired primary teachers by her energy and flair, found innovative ways to provide suitable art materials, and saw to it that 'wool and clay rapidly became the dominant craft materials'. [19]

From 1951 Blumhardt had a major influence as head of the art department at Wellington Teachers' College, and also as a regular tutor of evening classes in weaving and pottery, attended mainly by women at home determined to expand their horizons. Some of her students, like those from similar classes elsewhere, went on to become distinguished craftswomen themselves. Others helped to swell the appreciative market for handcrafts fostered by the new school curriculum, increasing affluence, and the growth of an intellectual elite which invested weaving and pottery in particular with moral as well as aesthetic value. Meanwhile other women were eagerly seeking out the embroidery classes run by English immigrants with strong connections to the London Embroiderers' Guild.

Organising from the 1960s

Once the groundwork was laid for the major craft revival of the 1960s, the craft organisations began to find their feet. Women were heavily involved in this process. They were prominent in the developmental post-war years of pottery, co-operating closely with the men on a thoroughly equal basis across all aspects of their craft, including technology. From the outset they held key positions, notably in organising and selecting for exhibitions, on the magazine The New Zealand Potter (edited by Helen Mason, 1958–68), and in the New Zealand Society of Potters (founded in 1965). As a local tradition developed, the influence of women such as Blumhardt, Mason, Yvonne Rust and Beryl Jowett was acknowledged, and on the whole they retained their place in the historical record (even if they were repeatedly referred to as 'accepted international craftsmen'). So it is not surprising that no women potters' groups formed.

Pottery had no strong associations here with either gender. Committed, highly skilled women using the traditional techniques of fibrecraft (including quilting, knitting, and embroidery) to produce innovative, attractive work found it harder to win recognition. The significance of gender was highlighted by the amount and type of attention paid to the few men using these techniques; for example, an ignorant critic wrote of a male quiltmaker in 1983: 'There can be no doubt that his skill and inventiveness have raised a pastime which was formerly regarded as one step up from occupational therapy to the level of an important art form.' [20]

As national organisations formed, they started working to reform these attitudes, aided by women such as Nan Berkeley, the dynamic founder of the New Zealand Chapter of the World Crafts Council (1964); she arranged for embroidery and weaving – including taniko work – to be shown with pottery, jewellery, ironwork and enamelling at a major craft exhibition in Stuttgart in 1966, four years before weaving was officially accepted here as an art form. But the most profound challenge to the lower status of 'women's crafts' was to come from what became known as the women's art movement.

Far-reaching changes had taken place in the arts environment by the mid 1960s. Painters had less need of art societies or other groups: dealer galleries had become an established feature since Helen Hitchings opened the first in Wellington in 1948. There was greater general awareness, and growing approval, of what New Zealand artists were doing, and even the public art galleries were less conservative than they had been in the 1940s, when Christchurch had refused Frances Hodgkins' 'The Pleasure Garden'. However, women artists’ work remained considerably less likely than men’s to be shown and collected.

New Zealand literature was starting to be taught in the schools and universities, local publishing firms were expanding, and reprints of earlier works were appearing. Both government and private patronage of the arts had been increasing since 1946, when the State Literary Fund began; in 1963 the Arts Advisory Council became the Queen Elizabeth II (QEII) Arts Council. By the 1970s several prestigious writing and painting fellowships and competitions were being sponsored by businesses. But the more complex the arts world became, and the more it relied on professional gatekeepers, the more difficult women found it to gain and keep a footing there.

In 1973 the first United Women's Convention featured a multi-media exhibition of contemporary women's work, organised by the Auckland branch of Zonta. By the mid 1970s, news of the 'women's art movement' and the work of theorists such as Lucy Lippard was arriving here. Women began to document the dearth of women's work in major shows and public purchases, publishers' lists and dealer galleries, courses and historical surveys, and to analyse what kind of attention it received when it did appear. Feminist arts-related groups were soon burgeoning.

The groups' immediate, practical aims were to encourage women to produce work, especially feminist work (though there was extensive debate over what that comprised); to offer alternatives to the established structures; and to lobby for a more equitable share of establishment attention and funding. As the accounts here and in publications such as A women's picture book (1988) show, activists tended to work across several fields. In 1974, the Christchurch Women's Art Group first brought together several women who would later be prime movers in organising the women's art environment at the 1977 Christchurch United Women's Convention, and in starting Spiral, Kidsarus and The Women's Gallery. Anna Keir was one: 'We met weekly to discuss our work and problems. This was the first time ... I consciously realised that some of the problems encountered at art school could be placed in a social context.' [21]

Women writers had similar experiences. In International Women's Year, 1975, nine had their first volumes of poetry accepted by publishers who had suddenly noticed the scarcity of women in their lists. One was Rachel McAlpine, who started to write after joining a local women's group and hearing Sam Hunt's views on women poets. 'Feminism had been in the air, and around 1973 or '74 it all started to make sense ... I suddenly learned how few women poets were being published ... I wanted other women to have one more role model, one more poet to identify with.' [22] Feminism provided the audience; the feminist (and often collectively run) journals, presses, publishers and bookshops, beginning with Broadsheet (1972), Herstory Press (1974), Spiral (1975), the first Kidsarus (1976), and Dunedin's Daybreak Bookshop (1977), supplied the means to reach it, and to convince commercial publishers that a viable market existed for new work by and about women.

By the end of the 1970s the focus had shifted, paralleling a similar shift in the women's movement generally, from finding and putting back the 'missing' women artists and writers, past and present, to examining how and why they had become lost or marginalised. The broad conclusion was that 'the way in which women artists [and other 'outsiders' such as indigenous artists] are recorded and described is crucial to the definition of art and the artist in our society'. [23] It was this excluding definition which had to be changed.

Breaking down the longstanding divisions between the fine arts and crafts, especially the fibrecrafts (both Pākehā and Māori) traditionally associated with women, was one effective strategy. Groups such as the Association of Women Artists and The Women's Gallery (both effectively starting in 1980) organised innovative group shows which celebrated 'women's work'. They encouraged craftswomen to use fine art skills and media, and women artists to turn to fabrics, fibres and their associated techniques, as well as to photography, film, video and performance art. They fostered collaborative projects, throwing standard concepts of 'individual talent' and 'originality' into question. All these strands were combined in 1984, when the Fabric Art Company, a group of seven Wellington women who met at a WEA fabric art course in 1981, took up Wellington City Art Gallery director Ann Philbin's invitation to create the Stuffed Stuff Show. A highly complex exhibition, at once original and accessible, strongly political and serious yet extremely witty, it toured for two years, and was seen by 15,000 people in Wellington alone, including many who had never been to an art gallery before.

Fabric Art Company

‘Hemmed In’ and ‘Breaking Out’, fabric sculptures, Val Griffiths-Jones (Fabric Art Company artist), 1986.

The existence of writing or fine arts groups which specifically excluded men was understood and supported by some men, but the dominant reactions were dismissal, ridicule, and hostility – particularly toward explicitly feminist groups. Some women artists, too, disapproved of all-women groups, publications or exhibitions. Yet the many fibrecraft groups whose membership consisted entirely or almost entirely of women were not viewed in the same light.

Linking gender and the arts in feminist analysis at first provoked much the same outraged reaction from the arts establishment as overtly linking politics and sport did from the rugby establishment. Such attitudes remained in the early 1990s, and continued to find platforms (including on social media). But over time, the second-wave arts groups and the work they fostered succeeded in substantially altering the broad context in which women's work was received.

The fibrecraft groups continued to flourish and to promote the work of their members. In 1981 a group of textile artists started the Craft Dyers' Guild, whose members work in silk painting, batik, embroidery, patchwork, weaving, leatherwork, paper-making and felt-making; and in 1982 the New Zealand Lace Society was formed. Quilting groups rapidly expanded, with approximately 750 women attending the 1993 National Symposium. In the 1980s Māori women began to form their own arts and crafts associations, such as Aotearoa Moana Nui A Kiwa Weavers in 1983 [later Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa] and Haeata in 1986, often with strong support from existing groups.

Like many groups inspired by the women's movement of the 1970s, most of the early feminist arts groups were no longer active by the mid-1990s; much of their agenda and energy had been safely absorbed by the system without fundamentally changing it. Yet their collective endeavours, building on those of their predecessors, had resulted in a much more extensive range of work by and about women being created on women's terms, becoming accessible to a broad audience, and in some cases winning recognition both at home and abroad.

1994–2019

By 2013, ‘creative arts’ was the fifth most popular field in which women held post-school qualifications. [24] Successful self-taught practitioners continued to emerge, but formal training of some kind had become the accepted norm for aspiring workers in all artistic fields. At their best, these courses offered focused professional guidance and a like-minded community, equivalent to what had long been available for fine arts students.

Writing: A much higher profile

By 2000, several universities and other tertiary institutions had set up creative writing courses, and places in the best known were highly sought after. [25] Except for script-writing, women usually made up a clear majority of those enrolled. [26] Committing to one of these courses meant that as a writer, ‘you take yourself seriously and read yourself critically’. [27] Given the declining financial rewards from writing for all but a few prize-winning stars, teaching in such courses could also help experienced writers to support their own work.

As author and University of Auckland course convenor Paula Morris noted, such courses were ‘going to be too costly and impractical for many Māori and Pasifika writers’. [28] She contributed to Te Papa Tupu, the mentoring programme developed by the Māori Literature Trust and organised by Huia Publishers. Another alternative was a free Massive Open Online Course (MOOC); the prestigious International Writing Programme at the University of Iowa was to offer these in 2019.

By 2018 a striking number of prominent award-winning women, such as Eleanor Catton, Tina Makereti and Paula Morris, were creative writing graduates. Long-established women writers were also gaining more recognition. Aspiring female writers thus had many more local role models than in the past. [29]

In 2013 Eleanor Catton became the second New Zealander, and youngest ever writer, to win the Man Booker prize for her novel The luminaries.

Moreover, it had become acceptable for fiction, non-fiction and poetry to deal with subjects deeply relevant to women’s lives, including sex, sexuality, misogyny and motherhood, that male critics had earlier deemed to be beyond the pale, or of no genuine literary merit or even interest. In fiction, non-fiction and poetry, women writers were also reaching out to a broader range of audiences through culturally complex works drawing on their diverse traditions and histories. These shifts were welcomed by the female readers making up the majority of book groups and writing festival audiences. [30]

By the mid 2010s more women were making commercial publishing decisions, holding senior positions in funding bodies, or heading prestigious non-profit publications such as the venerable Landfall. [31] Yet overall, conventional publisher and retail outlets for local books, particularly fiction, were shrinking. By 2013, after company withdrawals, downsizings and mergers, local fiction publishing had become ‘dominated by two companies: Penguin Random House and Victoria University Press’, and the growth of global winner-take-all bestsellers and online retailers was also pushing new local authors aside. [32] More encouraging were the growing ranks of smaller independent New Zealand publishers, often run by women, scoring some notable successes. [33] Individual self-publishing, though increasingly common, rarely had similar impact.

As communications technology developed and spread, in addition to connecting through courses, women writers formed new digital writing groups. These often attracted both experienced and novice writers (as the original New Zealand Women Writers’ Society had done). Offering easily accessible mutual support and a controlled form of online publishing, they were well received, especially by women with young children. Emma Neale would have welcomed such groups when she began writing: ‘Isolation is always a problem for writers, and at that stage women can be really vulnerable.’ [34]

Yet the internet also enabled the rapid spread of online abuse of women writers, especially those expressing feminist and anti-racist ideas. In August 2018 the New Zealand Society of Authors (NZSA), citing new evidence of how ‘women writers in New Zealand are targeted for abuse’, called on media outlets ‘to follow the protocol adopted by overseas news-makers and ban anonymous online comments’ – to little effect, as misogyny was not classed as hate speech.[35]

Art: Unequal opportunities

In 1994, women made up only 17 per cent of artists represented in the national collection and had created 19 per cent of the works held. [36] By 2018 women artists, like writers, seemed to be finding it less difficult to win a more equitable share of recognition. Between 2001 and 2017, five of the ten artists chosen to represent New Zealand at the Venice Biennale were women. They were also becoming more equitably represented among main Wallace Award winners, and the senior staff of public institutions and commissioning bodies. [37]

The problem was whether women were ‘being equally enabled when it comes to maintaining an active art practice’. [38] Women had long made up a majority of art school students – at least 80 per cent by 2018. Yet art schools still had very few women professors or associate professors, and dealer galleries continued to represent predominantly male artists – generally around 70 per cent, though at some it was over 80 per cent. Only a few dealers, mainly women, represented a majority of female artists. Auckland dealer Anna Miles, with around 73 per cent female artists, commented:

Firstly, a dealer gallery is a conduit to new artists. Secondly, it offers an individual vision or perhaps at its most critical, a counter vision … Both these aspects of the dealer gallery I interpret as expansive. I do not want to contribute to a narrowing of the curatorial band-width. To be critical I believe you need to be panoramic. You need to look as widely as possible across the field and conversely as deeply as possible. [39]

Estimations suggested that roughly four out of five contemporary pieces bought by public galleries continued to be by male artists, who were also favoured in large private collections of contemporary work. This had far-reaching consequences, because a major collection:

doesn’t just acquire artworks, it inscribes histories. It creates a resource for future curating, and so its in-built biases last for far longer than the current moment we are in. [40]

Overall, graduating male art students were estimated to have a 15 times greater chance than female students of being represented.

While women artists and academics discussed these issues both among themselves and in the arts media, no new groups seem to have formed specifically to address them. By 2018, however, they were clearly receiving increased attention, partly because the ‘battlelines of social equality’ had ‘sharpened of late ... in light of the unhappily small gains made towards equitable representation and employment opportunities’. [41]

Jason Oxenham, New Zealand Herald, 19 Sept. 2018.

For the 125th anniversary of women’s suffrage in 2018, the University of Auckland put on the exhibition Say So: Voices of Protest and Pause. It showed artworks by women from the university collection, chosen by twelve students in the postgraduate art history programme. They included (left to right) Alice Karetai, with Mana Wahine Māori by Robyn Kahukiwa (1993); Kirsten Raynor, with Inseparable Huia by Fiona Pardington (2016); and Finn McCahon Jones, with Persimmons by Jennifer French (1985).

Femisphere, a ‘zine produced annually by Imogen Taylor and Judy Darragh from 2017, focused on ‘the full, diverse range of women artists connected with Aotearoa New Zealand, with particular attention to women of diverse ethnicities’, noting that ‘women’ was ‘inclusive to all variations of gender that identify with the term/label of ‘woman’ or ‘female … in the present, past or future’. It aimed to provide ‘both publicity and serious critical attention, in order to gain wider recognition of [women’s] work’, and to highlight ‘issues to do with social change (and the lack of it) in relation to women artists of Aotearoa New Zealand’. [42]

Women artists found ways to deal with feminist and decolonising themes in their work. They featured prominently among those who challenged the ‘art-market value system, which privileged the commodifiable art object’, turning instead to ‘installation, site-specificity and temporality in order to evade easy categorisation’. [43]

Another striking move was to form art collectives. Pacific Sisters, involving both Māori and Pacific women, was strongly active in Auckland in the 1990s and early 2000s. When Te Papa held a major retrospective in 2018, the collective believed that much of the credit for this should go to Nina Tonga, appointed Te Papa’s first Curator Pacific Art in 2017. [44] Another women’s art collective becoming much better known by then was Mata Aho, set up in 2012 by four Māori women artists.

A unique women’s art collective based on the experience of domestic violence was begun in 2013 by Karen Seccombe, who was studying for her Masters in Māori visual arts. Starting with seven women, by 2019 the Women’s Art Initiative (WAI) encompassed 52 women in Manawatu and Marlborough, and had held 11 exhibitions. As Seccombe explained in her account of the group:

The quality was consistently high – many of the members had arts qualifications and/or had spent years as makers. Their aspirations and ideas were limited only by their access to equitable funding. Exhibited art works were rarely for sale – for many women, these works were deeply personal and too hard to let go.

Crafts: Resurgence and blurred boundaries

‘It enriches my life’

Susan H. knew how to knit, but hadn’t done much for a number of years, and decided she needed to upskill. She joined the weekly Southern Cross Stitch n’Bitch group in Wellington: ‘It was so non-threatening, such nice people. It got people together – women and a couple of young guys, all different ages and cultural backgrounds, mostly living in the inner city.’ Later, exploring the internet, she found ‘Kiwi James’, a blogger in the Wairarapa, and introduced herself to him at a Knitworld Wellington workshop weekend at the Dowse Art Gallery (where she was thrilled to come second in the fastest knitter competition). She also travelled, with her new knitting friends, to a monthly Wairarapa knitting group he organised.

In 2009, she went to the first Knit August Nights retreat in Napier, and has gone every year since. As she became more confident with her skills, she started teaching there herself. She made many friendships in Wellington knitting groups, and found new friends and connections through Ravelry, which she joined at the beginning in 2007. By April 2019 she had over 9000 patterns stored on it, many acquired for free, and had knitted 116,309 metres of wool in 175 projects. ‘Ravelry has changed my knitting life. I’m definitely addicted!’

As well as knowledge, creativity and enjoyment, involvement in the knitting revival greatly increased Susan’s confidence and self-esteem. ‘For me, knitting is a very soothing, calming thing to do – this year I had a major operation, and knitting was so important in keeping me calm and occupied before and after. It enriches my life – especially the variety of friends with a common interest.’

From the 1990s, professional crafts training was offered by schools of craft and design in Dunedin and Auckland, and later at Massey. By the 2010s, hand-made domestic items and furnishings were again becoming fashionable, positioned as unique, local and sustainable in contrast to global industrial products, and the distinctions between ‘arts’ and ‘crafts’ were becoming blurred.

The large textile crafts organisations of 1993 remained active in 2018, testifying to the continuing popularity of these creative forms. The Association of New Zealand Embroiders’ Guilds and the New Zealand Spinning, Weaving and Woolcrafts Society, which became Creative Fibre in 1998, continued to work hard to enhance the status of their crafts. While their members were almost entirely female, some men did take part.

Supported by the possibilities of the internet, there was rapid expansion after 2000 of more casual groups which enabled a wide age range of women to combine flexible exploration of textile crafts, especially knitting, with fun and friendship. The handcraft revival was part of an international movement spread by the internet, particularly through blogging. Knitters began posting and sharing blogs about their projects, and writing articles. Other online sources, including YouTube and two massively influential websites, Knitty.com and Ravelry (an international network for knitters and other fibre artists), stimulated people’s interest, provided both inspiration and instruction, and connected knitters with each other.

As part of the resurgence in knitting, New Zealand knitters started to meet up in the 2000s in informal groups. Knitters got together at public places, including libraries, community centres, yarn shops and cafes, often at a regular time and place, but with no sign-up or RSVP necessary. Some of the groups had a wide range of ages, but they tended to be predominately Pakeha, middle class women.

The revival of knitting and crocheting led some New Zealand crafters to monetise their hobby. Some sold their finished products to non-crafters, while others developed products for crafters themselves, for example by becoming independent yarn dyers and pattern designers. [45] In the 2010s, craft festivals, featuring a mix of marketplaces and classes, emerged as another form of craft organising. Knit August Nights (KAN) began in Napier in 2010 and the first Unwind Fibre Retreat was held in Dunedin in 2012. In 2019, both were still running. [46]

Despite the decline in knitting in the 1980s and 1990s, a long history of knitting for charity continued. Within the revival, knitters pursued this form of volunteer work through both traditional and new online structures. For example, knitting volunteers, organising mostly through word-of-mouth, created thousands of items of woollen clothing and blankets for the Neonatal Trust; [47] Little Sprouts, working with charity partners to send out baby packs, had more than 1000 members marshalled via its Facebook page in 2019. [48]

Among Māori craftswomen, weaving continued to predominate. Internal funding changes resulted in Aotearoa Moana Nui A Kiwa Weavers, which had originally represented both Māori and Pacific weavers, splitting in 1994, with the Māori group becoming Te Roopu Raranga O Whatu. The development of courses run by a new generation of tertiary weaving teachers was ‘a key element in the resurgence and strength of weaving’, and attending the biennial National Weavers’ Hui became part of the requirements for many weaving courses. [49]

Groups of Pacific women, too, were continuing to develop their textile crafts, gaining wider visibility and recognition. In 2018, for example, a group of Cook Islands women formed Vainetini o Manawatū to create a tīvaivai manu tātaura (appliqué and embroidered quilt) on the theme of coming to Aotearoa New Zealand and making the Manawatū their home. It was specifically made for the exhibition Taku P’eu Tūpuna, at Te Manawa in Palmerston North, with a film where the women showed how it was created. They intended to continue meeting and creating tīvaivai.

YouTube: Taku P'eu Tupuna

This video shows Vainetini o Manawatū, a group of

The persistent divide between arts and crafts also appeared to be breaking down further. By 2018, students at Elam were reported to be showing new interest in incorporating craft techniques and materials into their practice. Elam fine arts student Indigo Poppelwell, focusing on domesticated crafts, noted that ‘Historically, domestic crafts have been used to keep women’s imagination in acceptable spheres, but I want to use the same crafts to set women’s imagination free.’ [50] Meanwhile increasing numbers of gallery exhibitions featured ‘object art’, including both ceramics and textiles.

The growing population of Pacific and Māori urbanites ‘created the conditions for a creative boom’. [51] Both individual artists and collectives featured highly innovative practice, often with political implications, involving textiles.

By 2018, for example, the Mata Aho collective had created and exhibited six major art projects combining contemporary textile/industrial materials and Pākeha crafts with Māori crafts and culture. They used black faux mink blankets for Te Whare Pora; reflective tape, as on hi-vis vests, for Kaokao; embroidery based on pare kawakawa, green mourning garlands, for Stop Look Listen; tarpaulins for Kiko Moana (made by invitation for documenta14 in Kassel, Germany); and 12-mm-thick marine-grade rope, rewoven with taniko techniques, for Tauira.

Pacific Sisters, too, were intent on innovation:

Growing up as first- and second-generation Pacific Islanders and urban Māori in Aotearoa, the group’s experiences were influenced just as much from street culture and hip hop as they were by oral histories. Faced with nothing that reflected their own experiences, the Pacific Sisters made what they wanted to see (and wear) ... contemporary accessories with traditional items, using a mix of natural and recycled materials. [52]

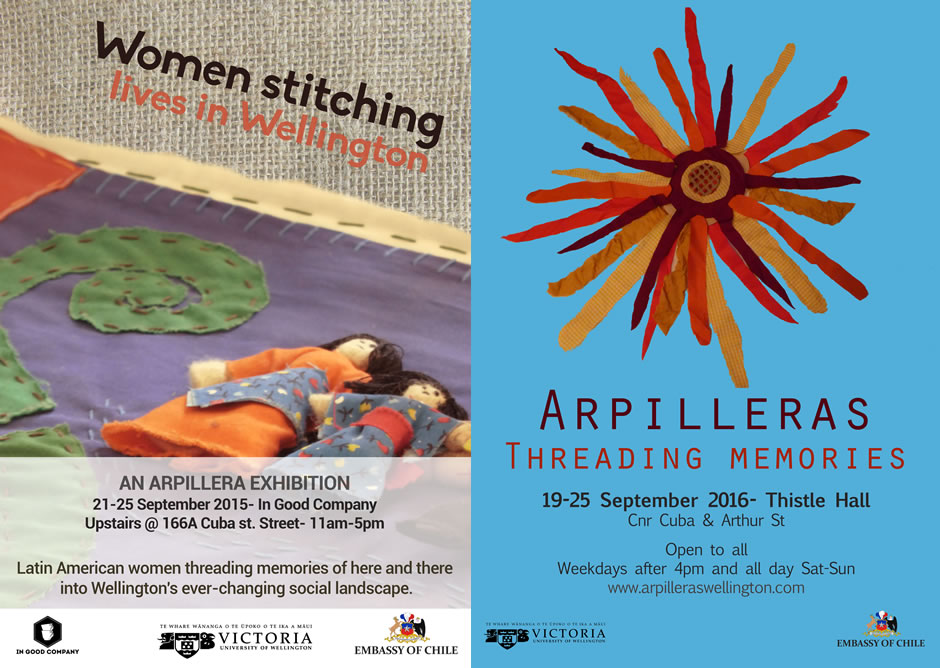

As the introduction to Women Together shows, groups of more recent migrants were also experimenting with textile crafts, for example the Wellington Arpilleras Collective. Small hand-sewn pictures made from fabric scraps, arpilleras were:

first made in Chile by female relatives of victims of the dictatorship in the 1970s, and since then have been produced in different parts of the world. Arpilleras are simple and powerful objects. In them are threaded the affective, intimate and political realities of the arpilleristas (the makers). [53]

In 2014 a group of Latin American women formed to create their own contemporary arpilleras, stitching ‘resistance, memory and the search for a more just and peaceful world’. In 2015 they staged an exhibition in Wellington, presenting ‘tales of the dreams, joys, contradictions and sorrows we have encountered while making Wellington our home’. It included both finished and unfinished arpilleras, ‘acknowledging the messy and personal process of producing our pieces’, along with one made by the collective and two historic arpilleras. [54] A second exhibition followed in 2016.

Wellington Arpilleras Collective

Posters for Wellington Arpilleras Collective exhibitions held in 2015 and 2016 in Wellington.

A wealth of hindsight

The 125th anniversary of women’s suffrage in 2018 and the associated funding available supported a surge of relevant publications, exhibitions and events, just as the 1993 centenary had done. In arts and crafts, the history of the women’s art movement was commemorated; for example, the 1996 Association of Women Artists postcards exhibition ‘Envoys’ was remounted as ‘Envoys Onwards’, with a new generation of women artists invited to contribute. The online publication Spiral Collectives brought together ‘significant Spiral and Women’s Gallery texts and updated histories of key members and activities’. Various symposiums and panel discussions included ‘No Common Ground’, which focused on addressing histories of feminist art, mana wahine and queer practice. [55] Publications such as Femisphere also dealt with these themes, and with the continuing evidence of prejudice and discrimination.

Martha van Drunen

The Suffrage in Stitches exhibition, held at Wellington Museum in 2019, was made up of 546 individually designed and stitched fabric panels, representing the 546 pages in the 1893 women’s suffrage petition. Workshops run by St Vincent de Paul’s Vinnies Re Sew (with funding from Creative New Zealand’s suffrage anniversary fund) brought together women ranging from a handful of professional artists to some who had never sewn before to meet and create. Each panel honoured a woman who signed the 1892 or 1893 petition (in many cases related to the maker) or who had inspired them. Their displayed panels were 300 metres long, matching the length of the original petition, and included 27,000 individual hand stitches.

A 2015 statement on art and feminism can be broadened to apply to a wide range of contemporary practice by women writers, as well as arts and crafts workers:

There is still the drive to uncover institutionally overlooked women artists through original archival research; we continue the project to craft an art-critical language grounded in alternative values; representation remains a key focus as we try to do sex, desire and feminine experience differently and render the relationship between viewer and artwork more intimate; and equal-opportunity feminism’s call-to-arms still motivates.

However, in the twenty-first century:

contemporary artists and theorists have the benefit of a wealth of hindsight…. the tools of feminist critique are still yielding valuable new insights, both about historical and contemporary art, while at the same time providing sources of strength to combat the effects of ongoing social and institutional misogyny. [56]

Anne Else

Notes

[1] Joanna Russ, How to suppress women's writing, The Women's Press, London, 1984, p. 107.

[2] Julie King, 'Art Collecting by the Canterbury Society of Arts: The First Fifty Years', Bulletin of New Zealand Art History, Vol. 11, 1990, p. 42.

[3] Between 1917 and 1920, for example, Frances Hodgkins and Wanganui-born Edith Collier exhibited in London with both, and in 1921 Collier stood for the committee of the Women's International Art Club. See Germaine Greer, The Obstacle Race, Secker and Warburg, London, 1979, pp. 321–23, on nineteenth century women artists' societies.

[4] Calhoun, 1990, p. 18.

[5] The Atom Quarterly: A Magazine Written and Illustrated by the Girls of New Zealand, Vol. 3 No. 1, March 1901, p. 4.

[6] Martha Vicinus, Independent women, Virago, London, 1985, p. 298.

[7] Catchpole, 1984, p. 113. Until the 1940s, most members of the independent groups also maintained working membership of their local arts society.

[8] Evelyn Page, interviewed by Prisciila Pitts, Wellington, May 1982; quoted in Catchpole, 1984, p. 3.

[9] Catchpole, 1984, p. 12.

[10] Robin Hyde, 'The New Zealand Woman in Letters', in Boddy and Matthews (eds), 1991, p. 189.

[11] Harding, 1990, p. 41.

[12] Dennis McEldowney, 'Publishing, Patronage and Literary Magazines', in Sturm (ed.), 1991, p. 563.

[13] Greer, 1979, p. 7.

[14] Harding, 1990, p. 24.

[15] Iris Hughes-Sparrow, 'The Taniko Weavers – Sybil and Josephine Mulvany', The Web, June 1984, p. 22. See also Janet de Boer, 'The Mulvany Sisters', Textile Fibre Forum, Vol. 6 Issue 1, No. 18, 1987, p. 44.

[16] Other early enthusiasts included Mrs Carling, a skilled weaver who emigrated to Nelson from England in 1918, and taught Perrine Moncrieff; and Mary Noble, who had studied at the Royal School of Needlework and London School of Weaving. When Hamilton Technical High School opened in 1920 with 27 pupils, she began 25 years of teaching handcrafts, including weaving, spinning, dressmaking and needlework, 'on the girls' side of the institution' (Weekly News, 23 May 1945, p. 10).

[17] Dominion, 4 November 1937.

[18] C. E. Beeby, The biography of an idea, New Zealand Council For Educational Research, Wellington, 1992, p. 141.

[19] Beeby, 1992, p. 141.

[20] New Zealand Crafts, No. 6, July 1983, p. 25.

[21] Anna Keir to Women's Art Archive, 8 April 1979.

[22] 'Rachel McAlpine', in Mediawomen, Celebrating women: New Zealand women and their stories, Cape Catley, Whatamongo Bay, 1984, pp. 181–82.

[23] Roszika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Old mistresses: women, art and ideology, Pantheon Books, New York, 1981, p. 3.

[24] The creative arts category covers qualifications in various aspects of arts and crafts, including Ngā Toi art forms, creative writing, design and communications.

[25] By 1996, for example, Victoria University of Wellington (VUW) was receiving 150 applications each year for the 12 creative writing course places available.

[26] This was especially true of creative writing MA courses, first offered by VUW in 1997: except for script-writing, in 2015–2018 women made up roughly three-quarters of enrolments.

[27] In 2018, average annual income from writing (mainly fiction, non-fiction and children’s books, with writers having 18 years’ experience on average) was $15,400 for women and $10,400 for men. See Horizon Research, Writers’ earnings in New Zealand, November 2018 (PDF).

[28] Hunt, Elle, ‘Write or wrong? The rise in the number of aspiring Kiwi writers’, NZ Listener, 9 July 2015

[29] Between 2003 and 2018, of the 16 sets of Prime Minister’s Literary Awards for outstanding long-term achievement, 8 for fiction went to women (as did 5 for poetry and 3 for non-fiction). In 2018 all but one of the 8 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards (down from 15 in 2008) were won by women, as were 6 of the 9 awards in 2019; more than half the winners had been female in 6 of the previous 10 years.

[30] Linda Burgess, personal communication; Barbara Brown, Book Discussion Scheme statistics, personal communication.

[31] The first female editor of Landfall, founded in 1947, was Chris Price, 1993–2000, followed in 2017 by Emma Neale.

[32] Chris Else, Janet Frame Memorial Lecture, 2018 (PDF).

[33] By 2019, for example, Mary McCallum’s Mākaro Press had published acclaimed works of fiction by New Zealand women, as well as autobiography and poetry. Bridget Williams Books and Awa Press (headed by Mary Varnham) focused on a wide range of non-fiction.

[34] Emma Neale, personal communication, 2018. Online writing groups included Airing Cupboard Poets; Brilliant and Amazing; and Kath Beattie’s Writing Group, starting in 1993, which went on to set up the Otago Writers’ Network.

[35] NZSA, ‘New Zealand Society of Authors (PEN NZ Inc) Te Puni Kaituhi o Aotearoa Supports Women Writers’, media statement, 17 August 2018.

[36] Jo Torr, Museum of New Zealand statistics, Association of Women Artists newsletter, Nov/Dec 1994.

[37] Between 2010 and 2017, in two years one woman won a main Wallace award, and in two years more than one did so. In the other four years men won all the main awards. In 2018, five of the six main awards went to women.

[38] Jack, 2018, p. 12.

[39] Miles, Anna, contribution to Women and the Arts panel, Culture Matters, Art History Society Symposium, Auckland, 16 Sept. 2018.

[40] Jack, 2018, p. 12.

[41] Millner et al., 2015, p. 144.

[42] Introduction, Femisphere 1, 2017. Issues 1 and 2 were free, thanks to funding from the Chartwell Trust and a private benefactor; in 2019 Creative NZ gave a Suffrage 125 Fund grant for later issues.

[43] Baker, 2018.

[44] Gordon-Smith, Inoa, ‘From the Margins to the Mainstream: Pacific Sisters at Te Papa’, Pantograph Punch, 18 April 2018. Available from: https://www.pantograph-punch.com/post/pacific-sisters

[45] The Knitographer, ‘The Knitographer Interviews… Spinning A Yarn’, 31 May 2014; Margaret Stove: Lace and Knitting as Art’, https://margaretstove.nz/books/publications/

[46] John Ireland, ‘Sticking to her knitting at craft event’, Napier Courier, 23 August 2017.

[47] The Neonatal Trust, ‘The support we provide’, https://www.neonataltrust.org.nz/about-us/support-we-provide

[48] Little Sprouts Craft Angels Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/groups/LittleSproutsCraftAngels/

[49] Te Roopu Raranga Whatu o Aotearoa, Māori Weavers New Zealand.

[50] Associate Professor Joyce Campbell, personal communication, 2018; Indigo Poppelwell, quoted in Tess Redgrave, ‘Four Generations of University Women’, Ingenio, Spring 2018, p. 26.

[51] Gordon-Smith, 2018.

[52] Gordon-Smith, 2018.

[53] See https://www.arpilleraswellington.com/about-arpilleras.html

[54] Ibid. See also https://nzhistory.govt.nz/women-together/introduction and https://nzhistory.govt.nz/women-together/theme/immigration-and-ethnic-groups

[55] ’No Common Ground’, Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, 7 July 2018. These websites indicate the range of arts-related events, etc. for Suffrage 125: Suffrage 125 Community Fund (Ministry for Women); Wāhine art projects boosted by suffrage fund (Waatea)

[56] Millner et al., 2015, pp. 144, 148.

Unpublished sources

Barrie, Lita, Women's Art Archive Interview Project, 1982–1984, E. H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Burgess, Linda, interviewed by Anne Else, Wellington, 2018

Catchpole, Julie Anne, 'The Group', MA thesis, University of Canterbury, 1984

Crabb, Helen ('Barc'), MS papers, ATL

Curnow, Betty, interviewed by Fiona McKergow, Auckland, 1991

Curnow, Betty,

Duffy, Mary Jane, 'The Christchurch Artists' Collective', MA thesis, University of Canterbury, 1989

Evans, Marian, 'The Women's Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand, Overview of Operations', typescript [n.d.], QEII Arts Council

Eyley, Claudia Pond, MS papers, ATL

Neale, Emma, phone interview by Anne Else, 2018

Paul, Janet and Kate Coolahan, interviewed by Anne Else, Wellington, 1992

Stirling, Heather, 'A History of the Development of the New Zealand Studio Potters' Movement, As Reflected in the New Zealand Potter Magazine', special-study, Brighton Polytechnic, 1979, AIM

Women's Art Archive collection, 1979–1980, Te Papa, Wellington

Woodall, Kate, 'Canterbury Women and the Arts and Crafts Movement 1906-1930s', BA (Hons) research paper, University of Canterbury, 1991

Published sources

Baker, Kirsty, ‘Before Words Get in Between’, Pantograph Punch, 28 September 2018, https://www.pantograph-punch.com/post/before-words

Batten, Juliet, 'Emerging From Underground: The Women's Art Movement in New Zealand', Women's Studies Conference Papers '8I, WSANZ, Auckland, 1982, pp. 67–74

Boddy, Gillian and Jacqueline Matthews (eds), Disputed ground: the journalism of Robin Hyde, Victoria University Press, Wellington, 1991

Calhoun, Ann, 'This, That and the Other: Donors, Women and Art Education', in Bequest to the nation, New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts, Wellington, 1990, pp. 17–19

Calhoun, Ann, ‘New Zealand Women Artists Before and After 1893', Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 4 No. 1, September 1988, pp. 54–67

Calhoun, Ann, The Arts & Crafts movement in New Zealand 1870–1940: women make their mark, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2000

Else, Anne, '"Not More Than Man Nor Less": The Treatment of Women Poets in Landfall, 1947–61', Landfall 156, 1985, pp. 431–64

Else, Anne, ‘The Daffodil Doyley’, Women's Studies Association Conference Papers, Dunedin, August 1987, WSANZ, Dunedin, 1988, pp. 47–52

Evans, Marian, Bridie Lonie, and Tilly Lloyd (eds), A women's picture book: 25 women artists of Aotearoa (New Zealand), GP Books, Wellington, 1988

Ewington, Julie, 'Past the Post: Postmodernism and Postfeminism', Antic One, 1986, pp. 5–21

Jack, Fiona, ‘Three Women One Day in March in the Year 2018’, Femisphere 2, pp. 8–13, reprinted from Counterfutures 5, http://counterfutures.nz/journal.html

Graham, Jeanine, 'Emily Harris: The Artist as Social Commentator', Historical News, No. 39, October 1979, pp. 6–10

Grattan, Kathleen, Sixty lively years, Penwomen's Club, Auckland, 1985

Harding, Brenda J., Women in their time: seventy-five years of the Otago Women's Club 1914-1989, Otago Women's Club, Dunedin, 1990

Kirker, Anne, New Zealand women artists, Reed Methuen, Wellington, 1986

Lewis, Margaret, Ngaio Marsh: a life, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 1991

Millner, Jacqueline, Catriona Moore and Georgina Cole, ‘Art and Feminism: Twenty-First Century Perspectives’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2015, 143–149

Nicholson, Heather, The loving stitch: s history of knitting and spinning in New Zealand, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 1998

Oliver, W.H., 'The Awakening Imagination', in W. H. Oliver and B. R. Williams (eds), The Oxford history of New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Wellington, 1981, pp. 430–62

Paul, Janet, 'Women Artists in New Zealand', in Phillida Bunkle and Beryl Hughes (eds), Women in New Zealand society, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1980, pp. 184–216

Roberts, Heather, Where did she come from? New Zealand women novelists 1862–1987, Allen & Unwin/Port Nicholson Press, Wellington, 1989

Spiral Collectives: an open research project, 2016–, https://medium.com/spiral-collectives

Sturm, Terry (ed.), The Oxford history of New Zealand literature in English, Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1991

Thompson, C. Hay, 'New Zealand's Women Writers', Cassell's Magazine, February 1909, pp. 307–11

Vinnies ReSew, Suffrage in stitches, Wellington Museum, 2–31 August 2019, https://suffrageinstitchesnz.tumblr.com/?fbclid=IwAR2auDqQML6cwR7zxBYIxYLbpPtG3gXUgP3rf-ijMVPgbTVQ5odJNX0UFhQ

Webby, Elizabeth and Lydia Wevers (eds), 'Introduction', Happy endings: stories by Australian and New Zealand women, 1850s–1930s, Allen & Unwin/Port Nicholson Press, Wellington, 1987