This essay written by Tania Rei and Rea Rangiheuea was first published in Women Together: a History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand in 1993.

Soon after the first Pākehā – mainly missionaries and traders – arrived in Rotorua in the 1830s, local Māori began to turn the inquisitiveness of the visitors to advantage by showing them the geothermal environment. The Pink and White Terraces at Rotomohana were the most popular sights, and a guide was essential. The best known were Sophia (Te Paea) Hinerangi (Guide Sophia) and Keita Rangitūkia Middlemass (Guide Kate), both of whom spoke fluent English. Selected by the local hapū, Tūhourangi, they received 15 shillings from each tour party.

A visit by Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, in 1870 promoted tourism, and during the 1870s other areas of interest were located, including Whakarewarewa. In the late 1880s, following the destruction of the Pink and White Terraces, Ngāti Wāhiao moved from Tarawera to Rotorua, and throughout the 1880s had 'complete control over the tourist traffic through Whakarewarewa. They erected a toll house at the entrance to the village, charging each tourist two shillings and sixpence, one shilling of which was a fee for the guide.' [1] The guides would meet visitors at the foot of the Pūārenga stream and piggy-back those who wished across it for 6d, then take them through the area. Guide Sophia, who had moved back to Whakarewarewa with her people, was exempted from this system and had no fixed fee. Her fame meant she was never short of customers, and she continued guiding until she retired in 1890.

Traditionally, it was the women of Tūhourangi and of Ngāti Wāhiao who acted as guides at Whakarewarewa. In the later 1890s the burgeoning forestry industry employed the majority of local men. Some of the women who remained at home could supplement their income by guiding, though it was a seasonal activity, and did not provide a steady income. The women were more appealing to tourists, and their natural flair and aptitude for the work reinforced their monopoly. Guiding was also compatible with the traditional puhi and kaitiaki role of Māori women. They grasped the opportunity to sustain themselves and their families by doing work they enjoyed.

The older guides, particularly those with moko, attracted the most customers; the younger guides learnt from accompanying the older women. All the families were related, and the tradition was handed down from generation to generation.

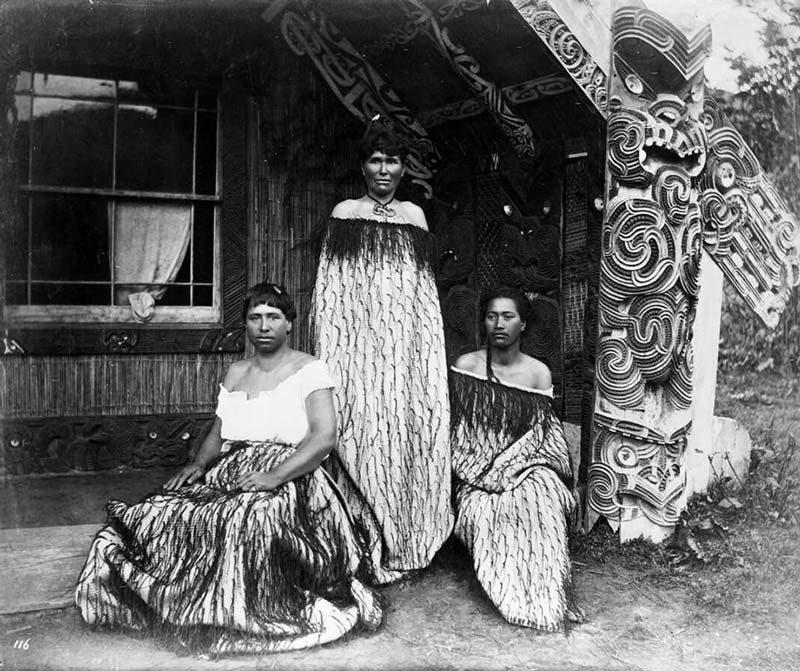

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-029217-F

Guide Sophia (Te Paea Hinerangi), pictured standing in front of the original Hinemihi at Te Wairoa in 1885. Guide Kate (Keita Rangitūkia Middlemass) is seated on the left; the third guide is unidentified. Sophia was the first of the Māori guides at the Pink and White Terraces, and later at Whakarewarewa.

The unregulated tourist industry allowed the women to work when and how it suited them. Some were accused of rushing their charges through so that they could pick up another fee, and squabbles over tour groups were not uncommon. Concerns about such behaviour, and about entrepreneurial practices occasionally bordering on extortion, prompted the government to take steps to mollify the public. Increasingly, too, land which had previously been owned by local Māori passed into government ownership. By the turn of the century most of the sightseeing areas, apart from the village of Whakarewarewa itself, were under government control. The change in ownership also precipitated changes in guiding practices.

When Guide Sophia was brought out of retirement to accompany the Duke and Duchess of York in 1901, she was assisted by the young Mākereti (Margaret Thom, also known as Maggie Papakura and Guide Maggie). [2] With her sister Bella, Mākereti did much to promote the tradition of guiding and the arts and crafts of their people.

In 1908 the guides were first issued with a licence and a black armband (later replaced by a numbered pin). But according to the best known of all the guides, Rangitiaria Dennan (Guide Rangi), guiding continued to be:

a hit and miss affair until 1910 when the Department of Tourist and Health Resorts began to license Māori guides and operate the government reserve on a more business-like basis. Guides had to be eighteen years old, pay . . . [an] annual licence fee, speak good English, produce character references and provide a photograph of themselves with their application. [3]

A road was put through the village and the chief, Mita Taupopoki, insisted that all guides be from Whakarewarewa, the exceptions being 'friends' of the families. The guides were subjected to a rigorous selection process, followed by a two-year probationary period. During the trial, they were periodically assessed by the Tourist Department and the senior guides. After Te Arawa Trust Board was established in the late 1920s, a board member tested the guides on Māori general knowledge.

Guide Rangi commenced guiding in 1921, and continued until she retired in 1965. When she began, she recalled, 'the reputation of some of the guides was not high. Some didn't care much about their appearance, or were unpunctual.'[4] She devoted her time to improving the image of her people, preserving their traditional knowledge and crafts, and educating others about her unique environment. People from all over the world asked to be guided by her.

To supplement their income, which was still seasonal, the women made piupiu and poi, and performed in evening concert parties, for which they recruited audiences from among the tourists they guided. A party of 40 toured Australia and England in 1910–11, with Mākereti as group leader and Bella in charge of the concert party itself. The uniform for this tour – white tussore silk blouse, red skirt and scarf, and piupiu for special occasions – became the official guide uniform. Elsie Rāponi recalls that when she began guiding in the early 1930s, all the guides had to belong to a concert party.

The Depression years gave rise to the practice of 'touting' for tourists. The guides coined the term 'vulture' for those touters who were over-zealous, seeking custom by jumping on the running boards of passing cars and other undignified behaviour. However, the strong bonds of kinship among them helped them through those difficult years. By the late 1930s, the average number of guides was 30.

In 1963 the Māori Arts and Crafts Institute was established, and in 1965 it established a ticketing system for tourists, which enabled it to take control by rostering guides. It paid dues to the owners of the Whakarewarewa reserve for permitting tourists access through their land. The guides continued to freelance as before.

By the late 1960s many of the older guides had retired, leaving a shortage. A number of young girls, many still at high school, were put through an intensive course arranged by the Institute, where they learnt the fundamentals of guiding and the importance of tourism. Although the course attracted favourable media attention, many of the girls were available only for vacation work, and the shortage persisted. In 1971, a pilot scheme with an emphasis on youth was organised, and a framework was developed to ensure adequate guide facilities. Both trainees and existing guides attended lectures, for example on vulcanology. This scheme was successful, and in 1972 ten guides were employed full-time. The older guides continued to freelance, but their numbers diminished as they reached retirement age. Tours set off every half hour, and this suited tour agencies better, as they knew guides would be available.

In 1983 the Institute evaluated the work of the guides. It was acknowledged that expertise in guiding lay not only in the ability to provide visitors with detailed background information on what they were seeing, but also in skills in traditional arts and crafts. The guides later received instruction from distinguished craftswoman Emily Schuster.

The formalisation of guiding eliminated the entrepreneurial character of the old ways. By the early 1990s many of the guides, unlike their predecessors, lived away from the village, and this too changed the nature of the work and the group.

Tania Rei and Rea Rangiheuea

Notes

[1] Waaka, 1982, p.89.

[2] Asked her 'Māori surname' by a tourist as she was standing beside the famous geyser Papakura, Mākereti answered 'Papakura'.

[3] Dennan, 1968, p. 73.

[4] Dennan, 1968, p. 74.

Unpublished sources

Māori Arts and Crafts Institute Annual Reports, 1963–1992

Rangiheuea, Rea, interview with Elsie Rāponi, Rotorua 1992

Rangiheuea, Rea, ‘The Social, Cultural and Economic Experience of A Māori Woman of Whakarewarewa During the Period 1942–1952, Merekorama’, BA research essay, University of Waikato, 1991

Rei, Tania, interviews with Emily Schuster and Guide Bubbles Mihinui, Rotorua, 1992

Te Awekōtuku, Ngāhuia, 'The Sociocultural Impact of Tourism on the Te Arawa People of Rotorua', PhD thesis, Waikato University, 1981

Waaka, Peter Kuru Stanley, 'Whakarewarewa: The Growth of a Māori Village', MA thesis, University, of Auckland, 1982

Wikitera, Keri-Anne, ‘Whakarewarewa Tourism Development: A Critical Analysis of Space and Place’, Masters thesis, Auckland University of Technology, 2006

Published sources

Dennan, Rangitiaria, with Ross Annabel, Guide Rāngi of Rotorua, Whitcombe & Tombs, Christchurch, 1968

Further information

Te Ara essay: ‘Te tāpoi Māori – Māori tourism’: https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-tapoi-maori-maori-tourism

Community contributions