This essay written by Sandra Coney was first published in Women together: a history of women's organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Margaret Sparrow in 2018.

1880s–1993

The one almost universal distinguishing feature of women's health groups has been a preoccupation with well women. Women's health work tends to be preventive. Its primary focus is to encourage and maintain a state of health or wellness, rather than provide services for the sick. Even where women's health groups have organised around 'illness', such as the modern groups providing support for women damaged by medical devices, they have also worked to prevent such mishaps occurring again, by warning women of the risks and lobbying for regulatory action.

Many groups arise because women perceive a lack within the formal social and medical services, and set out to rectify this. However, they then find that this involves being drawn into political action, since they are challenging those responsible for these services.

A central feature of all women's health work is providing information to women, so that they can take more control of their lives. The maxim 'knowledge is power' was as current in the nineteenth century as it has been among the women's health activists of the last 20 years. However, the kind of information provided has varied according to the social beliefs of the day. Because it is so intertwined with notions of morality and women's role in society, women's health work is deeply affected by current social ideology. As freedoms have been won, women's lives have changed, and aspirations have altered, the focus has shifted; yet there are often striking historical parallels, and persistent areas of concern.

The first stage of organising around health, from the 1880s to about 1905, was concerned with establishing women's basic right to health, for example through exercise, and with raising the moral tone of society, through 'clean living' for both sexes. In the second stage, from around the formation of the Plunket Society in 1907 until the mid–1920s, 'social purity' remained important but eugenic themes also came to the fore. Groups formed in the third period, between 1930 and 1970, concentrated on reproductive issues and physical health.

But as social expectations alter, the changes fought for by one generation of women may be experienced as restrictive by the next. This is illustrated by women's organising around birth. In the 1930s, women's groups agitated for hospital birth to be available for women as of right, and for all women to be offered pain relief in childbirth. By the 1950s, the almost universal hospitalisation of women for birth and routine use of analgesics led to a reaction, and women's groups began to organise to allow women more choices.

The organisations formed in the third period arose out of the community, did not have an authoritarian style, and were less moralistic than their predecessors. In these respects they foreshadowed the groups of the fourth period, the early 1970s to the 1990s. Often focusing on a single issue, such as abortion, birth, or occupational health hazards, most of these groups saw themselves as part of a loosely defined 'women's health movement', and their work was deeply influenced by the ideologies and organisational methods of the feminist movement.

For much of the twentieth century, 'women's health' was largely synonymous with 'maternal health' for governments, health system officials and many women's groups. In the 1970s and 1980s, this tendency was challenged by some Pākehā feminist health groups, who argued that women should be seen not solely as mothers or potential mothers, but as individuals.

Such arguments were related to the underlying theme in most women's health organising: women's bodies and who owns them. Organising often incorporated the tension between the way society expected women to use their bodies, and what women themselves wanted to do. Thus it contained both radical and conservative elements which were sometimes in conflict. Some women's groups sought to reinforce rather than challenge social expectations, seeing women's social role as superseding individual rights. Others, while accepting the expected female role, organised to improve the conditions under which women carried this out. Others again struggled to ensure that women had individual autonomy over how their bodies looked, how they used them, and how they expressed their sexuality and controlled reproduction.

A basic right to health: 1880s to 1905

In the late nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth, there were very few groups which could be defined as women's health groups. However, women's social action and welfare groups, such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) and National Council of Women (NCW), were strongly concerned with the health of women and girls. In the nineteenth century, women's normal biological functions were commonly believed to make them especially vulnerable to ill health, and menstruation was seen as a sickness. Women's supposed biological inferiority was used to justify their dependence on men and exclusion from much of the public sphere.

The early feminists challenged this stereotype. They argued that in woman's biological role lay her power, and that menstruation and maternity were natural rather than incapacitating functions. Women had a basic right to good health and could enjoy it if they followed simple rules for pure living.

Nineteenth-century New Zealand feminists were influenced by the progressive ideas of the American Popular Health Movement and the Grimke sisters. They had read Frances Power Cobbe's pamphlet The little health of ladies, which argued for a more active outdoor life for women, and Dr Alice Stockham's Tokology, which said that menstruation, pregnancy and childbirth were natural events which did not require women to be treated as if they were ill. [1] In 1894, May Yates, founder of the British Food and Bread Reform League, visited New Zealand and travelled the country talking to groups of interested people about healthy eating, with less meat and more vegetables. [2]

The general platform of these reformers was that people should adopt a lifestyle which was as 'close to Nature' as possible. Through temperance, fresh air, sunlight, exercise, vegetarianism, personal cleanliness and copious drinking of clean water, the body would be kept clean and pure. These concerns were all discussed in The White Ribbon (the WCTU newspaper), which published regular health articles, often written by Ada Wells of Christchurch. The remedies for disorders she suggested were firmly 'alternative'; they aimed at treating the whole person rather than the ailment, and restoring a natural 'balance'.

The medical profession had not then attained the monopoly over health care it would later achieve, and many people had recourse to home remedies, patent medicines, and alternative healing methods such as hydropathy and electric therapy. This was reflected in the attitudes toward health care expressed in The White Ribbon and the feminist newspaper Daybreak, and in papers given at NCW conventions. The widespread suspicion of the medical profession and the treatments it offered was shown in the opposition to the Medical Practitioners’ Bill, introduced in 1901, which would have made it an offence for anyone other than doctors to treat the sick. The White Ribbon declared: 'What has contemptuously been termed "quackery" has as much claim to our consideration as the methods which find most favour in the medical school.' [3] Drugs and surgery – called 'vivisection' or 'the knife' [4] – were seen as brutal, harmful treatments; even compulsory vaccination was roundly condemned by Margaret Sievwright as unnecessary in New Zealand, and as an invasion of parental rights. This perspective had parallels with the 'holistic' approach adopted by one strand of the modern women's health movement from the 1970s.

The conditions of women's lives in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries could cause health problems. Many women, especially the married, did not have the benefit of physical activity. Upper-middle-class women could lead relatively idle lives – hence the stereotype of the languid, decorative society matron, prone to the vapours – while working women, such as factory and shop workers and domestic servants, spent long hours on their feet. The heavy nature of housework, coupled with frequent child-bearing, meant that women with no household help were as prone to occupational health hazards as domestic servants. Prolapsed uteruses, back injuries, varicose veins and 'housemaid's knee' were common ailments, and patent remedies for them were frequently advertised.

Some of the earliest organising around health addressed these issues. The YWCA had as one of its three central aims the physical well-being of girls. Its focus was primarily young working women who spent long hours in factories or shops. In Dunedin, recreation classes were held from 1883, and in Auckland, gymnasium work was provided from an early date.

The demand for exercise for women was couched in terms of improved health status. Members of the Canterbury Women's Institute advocated 'the physical training of women and girls' through athletics, swimming and walking. [5] The women who started the early cycling organisations, such as the Atalanta Cycling Club, argued for the health benefits of this form of exercise. The White Ribbon had a cycling column; other writers promoted the benefits of walking, not 'taken in a listless way' but 'a brisk walk in the open air, in a cheerful spirit, with shoulders back, head erect, throwing some life into it … the life current flows more freely, and every organ of the body is benefited thereby.' [6]

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/4-005994-G

These sisters, photographed in Whanganui in 1886, are all heavily corseted under their tight-fitting, strained bodices and heavily draped skirts. Characteristic of the 1880s, this style of dress was much criticised by dress reformers and women’s health advocates during the 1890s.

Victorian and Edwardian women's clothing was acutely constricting: long heavy skirts were obligatory, and tight corsets were worn by women of all classes, often even during pregnancy, to make their shapes conform to contemporary notions of the ideal female body. Some Māori women adopted this habit. [7] Women's groups condemned 'waist-compression' as injurious to women's health, causing poor appetite, feelings of weakness and withering of the trunk muscles. The apparently short-lived Rational Dress Association followed British and American groups established to promote rational dress in both under- and outer clothing. It sold patterns for knickerbockers and provided practical information on how to give up corsets and strengthen 'Nature's corset' – the abdominal muscles. It also adopted the arguments of the German Dr Gustav Jaeger in favour of wearing woollen garments next to the skin, to enable it to breathe. Although only a small group, it received much publicity, featuring in widely read magazines such as the New Zealand Graphic. Other women's groups opposed to corseting before the First World War included the WCTU, whose Hygiene Department focused on dress reform and exercise, the Canterbury Women's Institute, the Plunket Society, and the Peace Scouts.

There was a moral element to much of this health work, as in other issues concerning women during this period. The metaphor for the body was a temple, which should be as 'clean' as the mind, with all 'impure' acts and thoughts driven out. Alcohol was condemned not just because of the social damage its abuse caused, but because it was physically and spiritually polluting. The social purity ethos espoused by most early women's groups aimed to encourage women to raise the moral tone of society by setting high standards of personal and sexual behaviour, and expecting men to meet them. Temperance, sex education, and prevention of venereal disease (VD) were linked concerns. The need to space births was acknowledged; VD was known to cause sterility and gynaecological problems in women, and blindness in infants born to infected mothers. But abstinence and self-restraint in both men and women were seen as the solutions; pre-marital sex was condemned, birth control and 'preventatives' (such as condoms) were not favoured, and the goal after marriage was 'a white life for two'. [8] The Contagious Diseases Act 1869, which allowed women suspected of being prostitutes to be compulsorily detained, examined and treated, was actively opposed by women's groups, such as the WCTU and the NCW, from the 1880s until it was finally repealed in 1910. Women objected so strongly because the Act assumed a double standard in sexual behaviour, threatening women's liberty but leaving men free.

The social purity model did not view women as sexual beings with desires of their own, but as the objects of men's lust. Sex education was seen as a necessity to protect innocent women, by warning them of the consequences of sexual activity before marriage, and various women's groups attempted to provide it. In 1895, the Canterbury Women's Institute petitioned the board of Canterbury University College for lecturers in biology for women, because 'ignorance is the rock on which so many young lives are stranded'. [9] However, this type of 'sex education' was really purity education, and gave minimal physiological information.

Social purity and eugenics: 1905 to 1930s

In the new century social purity beliefs continued, boosted by increased nationalistic fervour. A pronatalist perspective resulted in concerted efforts to encourage women, especially middle-class Pākehā women, to have more children. Eugenicist ideas were also widely held. Together these approaches provided the foundation for much women's health work from the 1900s to the 1930s. They were behind such diverse initiatives as the establishment of the Otago School of Home Science and better exercise programmes for girls within the school curriculum, both supported by women's groups.

The second period was marked by constant efforts (mainly among middle-class women) to impose particular moral beliefs on women and girls in general. If necessary, moral arguments were to be backed by regulatory force. Domestic science was to become compulsory for girls at secondary school, women health patrols were to tell young women how to conduct their private lives, and Plunket nurses were to exercise surveillance over women's child-rearing. The 'unfit' were to be firmly discouraged or even forcibly prevented from breeding. [10] The discovery that many First World War recruits were unfit for service, followed by the 1918 influenza epidemic which exposed the unhealthy condition of many New Zealand homes, reinforced such eugenicist arguments.

New Zealand Free Lance, 16 August 1939, Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-7171-15

The Gisborne Provincial Plunket Conference, 1939, where Plunket committee members from the Gisborne Province met with officials from Plunket's national office in Dunedin, including Gwen Hoddinott, Dominion secretary from 1917 to 1941, and Daisy Begg, Dominion president.

The aims of the Plunket Society were based on the teachings of Sir Frederic Truby King, whose personal philosophy was decidedly imperialist and eugenicist. Similar ideas found their way into Plunket pamphlets from 1907. Groups such as the WCTU, NCW, and Society for the Protection of Women and Children made submissions to the 1925 Committee of Inquiry into Mental Defectives and Sexual Offenders; the resulting report gave full expression to eugenic ideals, calling for compulsory registration of mental defectives, a prohibition on their marrying, and sterilisation in some circumstances. However, the ensuing legislation did not carry through these draconian recommendations.

From the mid-1930s, some prominent members of the Women's Division of the New Zealand Farmers' Union (WDFU) conducted a campaign for compulsory sterilisation of the 'unfit'. This campaign was hotly contested within the WDFU, but it did allow a booklet entitled The problem of mental deficiency in New Zealand, written by Nina Barrer, a leading WDFU member, to be published under its auspices. [11]

Continuing anxiety about VD was inflamed by controversy when many First World War soldiers were invalided because of infection. Ettie Rout's practical approach earned the opposition of women's groups such as the YWCA. Untreated VD had serious consequences for women and children, but it was also a moral affront: it transplanted the corruption of the world into the supposed purity of the home, threatening motherhood and 'the race'. Nevertheless, women's groups vigilantly guarded against any attempt by government to pass legislation similar to the old Contagious Diseases Act. The Social Hygiene Act 1917 provided for the compulsory treatment of both sexes and the appointment of plainclothes women's health patrols, who were supposed to advise girls found in streets and parks of the moral danger they were in. This measure was not entirely supported by women's groups such as the WCTU and NCW, as the patrols approached only women. The solutions the women's organisations sought were sex education, free clinics for the treatment of VD, and women police with a wide range of duties, including the protection of young women. They were against compulsory notification and treatment.

Women's groups commonly invited women doctors such as Dr Agnes Bennett and Dr Daisy Platts-Mills to deliver lectures on health topics, but in Christchurch women went further and organised a service to inform women about the diseases and available treatments. Like the Plunket Society, the Social Hygiene Society, formed in 1916, marked a new style in women's organising around health: both moved beyond lobbying and proselytising to take practical action on social and health needs from a public health perspective. Health services were also moving in this direction, with the Health Act 1920 strengthening the Department of Health and emphasising preventive medicine. Both Plunket and the Social Hygiene Society eventually received some public funding.

Dr Platts-Mills, the driving force behind the Social Hygiene Society, was also founding president of the Plunket Society in Wellington, and involved with the YWCA. Women doctors were increasingly becoming key figures in women's health issues. The opposition to orthodox medical practice which had characterised early feminist attitudes had disappeared, as doctors gained influence. Women doctors, obstructed in their ambitions to take part in mainstream medicine, concentrated on the more acceptable areas of women's and children's health. Women's health groups looked to doctors such as Emily Siedeberg, Hilda Northcroft, Maud Fere and Doris Gordon for their specialist knowledge and the advantage of their professional status in dealing with government agencies.

Reproductive issues and physical health: 1930s to 1960s

Reproductive issues – birth, abortion, contraception – dominated women's health work from the 1930s to the 1960s. Pronatalist arguments remained strong, with periodic public outcries about the falling birth rate and women's neglect of their maternal duties. Concern for the health of the nation was also evident in the increasing interest in national and individual fitness. Many new women's sporting organisations began, and physical education in schools became more systematic.

A new development was the increasing articulation of the needs and interests of individual women. During the 1920s and early 1930s, the maternal mortality rate was high and it was argued that women avoided motherhood because they feared the pain and danger of childbirth. Hospitalisation and analgesia during childbirth were seen as providing a safer, more acceptable birth experience. [12] Up until this time, birth had been largely in the hands of midwives, rather than doctors, and the concept of birth as a normal event had been supported from within the Department of Health. In 1920, 65 per cent of births took place outside hospitals.

Otago Daily Times, 19 June 1907, p. 43

Midwifery staff and new babies at St Helen’s Maternity Hospital, Dunedin, in 1907. In the centre, wearing black, is Dr Emily Siedeberg, superintendent of the hospital (and the first woman medical graduate in New Zealand).

The formation of the Obstetrical Society (later the Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society) in 1927 was a key factor in the medicalisation of birth. The society was established to protect doctors' interests in the birth area. Its chief architect was Dr Doris Gordon. Indefatigable in the pursuit of her objects, she had a strong influence on contemporary women's groups and was adept at enlisting their support for her campaigns. The Obstetrical Society argued that childbirth was a pathological event which required medical supervision. By the mid-1930s, 78 per cent of Pākehā babies (but only 17 per cent of Māori) were born in hospitals.

Women's groups backed the Obstetrical Society's arguments. In 1930, Dr Gordon orchestrated a major campaign by women and women's groups, such as the NCW, which raised £31,741 to establish a Chair in Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Otago. Groups such as the Women's Auxiliary of the Unemployed Workers' Union and the women's branches of the Labour Party supported calls for more pain relief in childbirth, especially in the St Helen's Hospitals. Representatives of 35 women's organisations sent a deputation to the Minister of Health about this in 1938. So dominant was approval of medicalisation among women's organisations that in 1930, when some women tried to prevent a proposal to allow medical students access to the midwife-controlled St Helen's Hospital in Wellington, they were defeated by a lobby spearheaded by women doctors such as Agnes Bennett and Sylvia Chapman, and supported by many women's organisations.

Two major inquiries into birth in this period had far-reaching consequences for women. In 1923, a Royal Commission investigated the deaths from puerperal sepsis of five women at an Auckland private hospital, and in 1937 a Committee of Inquiry into Maternity Services heard submissions from many women's groups. The 1923 inquiry resulted in the introduction of rigid techniques for asepsis in public hospitals; the second led to the first Labour government introducing provisions, via the Social Security Act 1938, for free antenatal and hospital care under the doctor of a woman's choice. Women's organisations were generally well satisfied with the outcomes of these inquiries, and felt that for once, women's wishes had been heard.

Another inquiry, this time into abortion, was held in 1936, occasioned by the number of women (most of them married) dying from septic abortions during the Depression years. Women's groups who made submissions included the Dominion Federation of Women's Institutes, Mothers' Union, NCW, Plunket Society, WDFU, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, Working Women's Movement, Women's Service Guild and Labour Party women's groups. While these organisations generally took the same pronatalist line as the committee of inquiry in condemning abortion, they were also concerned about the position of individual women, especially overburdened housewives. They almost universally argued for a motherhood endowment or family allowance which would enable mothers to have babies without financial strain, and maternity allowances to cover the costs of confinement. Some supported the establishment of birth control clinics for married women so that they could space their children, stating that this would if anything increase rather than reduce the population. They argued, perhaps for the first time, for 'the mother's right to say when she will bear children'. [13] In the event, the committee recommended against any liberalisation of abortion law, gave only lukewarm support for hospital birth-control clinics for married women, and appealed to women to have more children.

Prompted by the inquiry, some women had already taken the matter of informing women about birth control into their own hands. New Zealand women had become so desperate about access to contraception that some had written to Marie Stopes in Britain for help. [14] In 1936, a group of primarily left-wing women formed the Sex Hygiene and Birth Regulation Society (later the New Zealand Family Planning Association). This lay women's group unconsciously followed the model of the earlier Social Hygiene Society in providing information and referrals, although without the moralising. The society had straightforward practical aims, although it described its work in pronatalist terms. One early brochure proclaimed: 'New Zealand Needs Babies! … Women Want Babies! … Family Planning Means … Healthier Mothers. Sturdier Babies. Happier Homes.' [15] Until the mid-1970s, it would not usually provide contraception for single women.

Three other important women's health organisations were initiated the following year. The Women's Health League (WHL), a largely Māori organisation centred on Rotorua, addressed many of the same issues as Pākehā groups, particularly the health of women and children. Its aims included improving the feeding and care of Māori infants, advising about nutrition, and improving access to health care. This was not the first organisation formed among Māori women to foster improved standards of health. The Māori branches of the WCTU, formed in many parts of New Zealand from 1894, concentrated on social purity issues such as the abuse of alcohol and smoking. In 1902, there was a Raetihi non-smoking club whose members bound themselves 'to wean Māori wahine from smoking, by example and precept'. [16] The impetus for both the WCTU groups and the WHL came from Pākehā women, but Māori women took control of the WHL and made it their own.

The New Zealand Women's Food Value League continued women's interest in food reform, this time based on new scientific knowledge. The motivation for its formation was the poor health status of New Zealanders in the inter-war period and the failure of the Department of Health to address nutrition. The league aimed to improve the health of families by sharing information with its housewife members. The Health and Beauty Movement was interested in some of the same issues as the nineteenth-century dress reformers and early cycling clubs, although without their feminist motivation. It supported pronatalism and contemporary goals of racial fitness by providing classes to achieve good health for women, including one to 'promote safer and easier motherhood'. [17] But it was thoroughly modern in reflecting changed ideals of women's bodies and female beauty in the inter-war period.

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-C-16171-F

Members of the Christchurch Harrier Club out for a run, July 1935. There was a marked increase in women’s participation in sporting activities during the 1920s and 1930s.

The women's health groups established in the 1930s set an enduring style for such work, one which emphasised sharing information, support, and a self-help approach to enable women to gain more control over their lives. Action was based on a commonality of experience and interest. Women identified gaps in services and information through their own life experiences, then organised to fill them.

Although the Second World War weakened several of these organisations, as women turned their attention to the war effort, the post-war period saw growth in several areas. The Family Planning Association (FPA) opened its first clinic in Auckland in 1953. Parents Centres began as a Natural Childbirth Association in 1952, in reaction to the medicalisation of childbirth – an example of the way women have frequently had to undo the work of previous generations of women in the health area. Similarly, the La Leche League, formed here in 1964 to encourage women to breastfeed infants, was a response to the prevalence of bottle-feeding, a practice encouraged in the post-war years within obstetric hospitals and, to some extent, by the Plunket Society. Both Parents Centres and the FPA encountered a good deal of opposition to their work from individual doctors and the New Zealand branch of the British Medical Association, who saw these organisations as taking business away from their members, and opposed lay women meddling in medical matters.

Health in the feminist era: 1970s to 1990s

From 1930 on, women were progressively channelled into the medical system. In the 1970s, this medicalisation became a rallying point for modern women's health activists. Like their nineteenth-century counterparts, they insisted that female physiology and bodily functions were in themselves perfectly normal and healthy.

Women organised to lobby for changes in the way medical services were provided for women, and address issues of patients' rights, product safety and medical power. Other groups turned their backs on the mainstream health system and emphasised non-medical alternatives to women's needs and complaints. These two strands coexisted and overlapped. Issues of concern included eating disorders (the modern equivalent of the corset), smoking, alcohol dependence, miscarriage, damaging forms of contraception, new reproductive technology, mental health, and cosmetic surgery. Many groups were very small, local initiatives, often relatively short-lived. But all tended to see themselves as part of a larger women's health movement, and there was considerable networking among them.

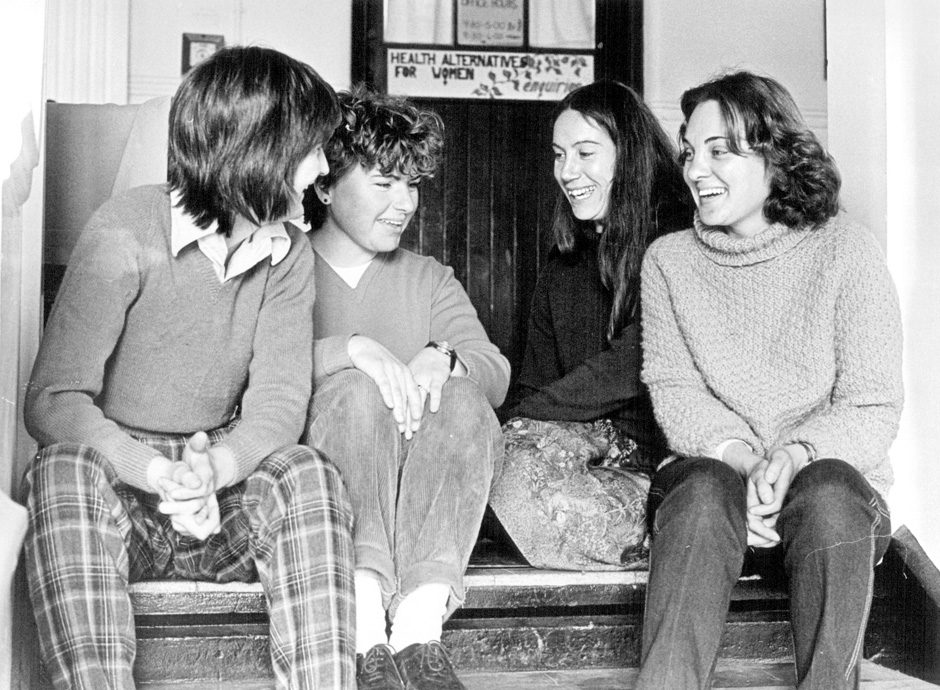

Stuff Limited

Four members of the Health Alternative for Women collective outside their Christchurch office, August 1983. From left: Dianne Ross, Ann Carrie, Christine Bird, and Linda Zampese.

The early groups were strongly influenced by developments in America. The work of the feminist health clinics established there was well known within New Zealand feminist circles. The women's health 'bible', Our bodies, ourselves, was published by the Boston Women's Health Book Collective in 1971 and soon became widely available in New Zealand. However, attempts to establish clinics along American lines, as the Auckland Women's Health Collective tried to do in the late 1970s, were not successful in New Zealand, with its tradition of free or cheap medical care. Groups such as The Health Alternatives for Women (THAW) which tried to provide even minor 'medical' services, such as pregnancy testing or cervical smears, also encountered opposition from health authorities.

The key concepts of what became known as the women's health movement were information, self-help, and women's autonomy over their bodies. Feminist women's health workers tended to see themselves as part of a long line of female healers and midwives suppressed by the church, state and medical professionals. The medical system was a 'powerful instrument of social control', and women had to wrest access to medical technology from the profession, whose victims they had been, while opposing its 'sexist ideology'. [18] Images of the witch and the Mother Goddess were frequently used, despite their Eurocentrism and dubious relevance to women living in the Pacific.

Though many of the issues addressed by the modern groups had preoccupied women for decades, the solutions they proposed were often startlingly different. In self-examination groups, with the aid of a speculum and mirror, the cervix was revealed and monitored. In 1973, Lorraine Rothman of the Feminist Health Centre in Los Angeles toured New Zealand at the invitation of the Organisation for Women's Health, demonstrating self-help techniques and menstrual extraction.

By this time the oral contraceptive pill and the injectible contraceptive Depo-Provera were on the market, as well as the Dalkon Shield IUD, and women began sharing information about their ill-effects. Thrush became almost epidemic among users of the high-dose pill, and women's health groups experimented with yoghurt and other home remedies. Defying legal restrictions on sex education, women's groups held seminars for schoolchildren and handed out pamphlets outside school gates. In 1972 in Auckland and 1973 in Dunedin, Knowhow groups were established, with counsellors providing information for single people by telephone. In the 1980s the FPA became a major provider of sex education programmes in schools, working within the law. Some conservative women's groups opposed such liberalisation, insisting that information promoted experimentation.

Birth remained a major issue, but unlike the earlier Parents Centres, which largely worked to humanise the hospital experience, groups in the 1970s and later – such as the Home Birth Association (1978), Save the Midwives (1983) and Maternity Action (1984) – worked mainly to promote the alternative of home birth, improve pay and conditions of domiciliary midwives, and restore the autonomy midwives had progressively lost. From the 1970s, the government and hospital boards closed small rural and urban maternity hospitals, including St Helens hospitals; this was vigorously opposed by such groups and by women in their local communities, though their efforts met with only partial success. [19]

However, women's access to safe legal abortion was the dominant issue of the 1970s. The more radical groups, such as the women's liberation groups and the Women's National Abortion Action Campaign (1973), supported the calls for total repeal of existing abortion laws and 'a woman's right to choose'. Other groups, such as the National Organisation for Women (NOW), wanted only liberalisation of the law, and there was some controversy in the Auckland branch of NOW when a small number of women opposed any stand in support of women's abortion rights.

Majority opinion was well ahead of Parliament: the Dunedin Collective for Woman's 1972 survey revealed that 75 per cent of the public wanted liberalised laws, and a 1973 Christchurch NOW survey of its own members found that 85 per cent wanted them. The first of several National Women's Abortion Action Conferences was held in 1973.

The opening of New Zealand's first private abortion clinic in Auckland in 1974 catapulted abortion into the public domain. There were police raids, court cases, and arson attempts. Women from Auckland Women's Liberation provided many of the counselling staff in the early days, and a plethora of women's groups formed to support the clinic politically. They included the Auckland Anti-Hospital Amendment Bill Committee (which organised a huge petition with 318,820 signatures), CORAL (Campaign to Oppose Repressive Abortion Law), and Co-Action. There were midnight poster-pasting campaigns, 'bus-ins' to Parliament, and in 1976 the Backstreet Theatre group toured New Zealand presenting the abortion struggle in dramatic form. Meanwhile women opposed to abortion, mainly on religious grounds, had formed Feminists for Life (later Women for Life) and were also involved in Pregnancy Help, set up by the Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child (SPUC) in 1975.

The government responded to all this controversy by establishing a Royal Commission on Contraception, Sterilisation and Abortion (1975–76), to which numerous women's groups made submissions. The outcome was a more restrictive law, the Contraception, Sterilisation, and Abortion Act 1977; it included prohibitions on the provision of contraceptive advice and information to under-16s, first passed in 1954, that were not lifted until the 1990s. The new law closed the Auckland abortion clinic, and feminists responded by organising a network of Sisters Overseas Service (SOS) groups which helped women fly to Australia for abortions. By September 1978, the Auckland group alone reported that it had assisted 1000 women. These groups progressively wound up after the clinic reopened a year later, and other abortion facilities found ways to work within the law; but in areas where access to abortion was difficult, SOS groups continued into the late 1980s.

The abortion campaign gave rise to new women's health projects. In Christchurch, THAW, formed as an outgrowth of the local SOS group, proved one of the most enduring. In Auckland, SOS work also developed into a health centre opened by the Auckland Women's Health Collective in 1979, emphasising alternative health approaches to health problems.

The first Wellington Women's Health Centre (1975) lasted for three days – the city council, which owned the premises, withdrew its support. It was followed by Hecate, which opened a Hot and Cold Doctor file to provide women with information on local doctors, a strategy also adopted by some of the groups which formed elsewhere in the 1980s and 1990s, for example in Palmerston North and Dannevirke. From 1977 to 1992, the New Zealand Women's Health Network published a newsletter which was distributed widely to women's health groups.

Two major conferences were held in this period: the government-organised Women and Health Conference (1977), and the National Women's Health Conference (1982). At the second, Māori women accused Pākehā health workers of racism in concentrating on uterine issues to the exclusion of more pressing issues for Māori, such as land ownership and a nuclear-free, independent Pacific.

Māori women had always had a broader definition of health issues than Pākehā groups, encompassing unemployment, housing, monoculturalism and poverty. The major health risks for Māori women up to the 1990s included lung cancer and heart disease, for which their rates were among the highest in the world. Like Pākehā groups, they preferred a preventive model of health, and worked at both community and political levels. Their concerns were usually directed towards the health of all members of the family, and in particular toward women as mothers. There was also an emphasis on nutrition and discouraging smoking. Some Māori women's groups formed in the 1980s and 1990s were outgrowths of hui (a Black Women's Day Health Hui was held in Otara in 1982). Others were community- or marae-based health initiatives to provide particular services such as cervical screening, testing for diabetes or immunisation. Within existing health services, special facilities were organised: for example, the Whānau Room at National Women's Hospital in Auckland, set up by Te Ūmere branch of the Māori Women's Welfare League to provide a whanau atmosphere for young expectant mothers, operated from 1987 to 1990.

Rapuora: health and Maori women, 1984, p. 14

Left to right: Elizabeth Rehu Murchie, research director of the Rapuora survey of Māori women’s health, Māori Women’s Welfare League president Georgina Kirby, and Miria Simpson, one of the Rapuora writers.

The league had a long-standing interest in health, starting with its housing survey in the 1950s. In the early 1980s it undertook a major survey of Māori women to measure their health status, covering diet, physical activity, smoking, weight, knowledge and use of traditional healing, and the interrelationship between life circumstances (such as employment) and stress. This ground-breaking study, conducted using new methods based on Māori cultural practices, was published by MWWL in 1984 as Rapuora: health and Māori women. [20] One direct outcome of the report was Whare Rapuora, a Glen Innes women's health clinic run by Māori women.

In 1984–86, two groups, THAW and Fertility Action, took action to initiate a Dalkon Shield removal programme, led by the Department of Health, and to take cases of New Zealand women injured by this IUD to the American courts. Fertility Action developed as a major voice for the women's health movement in the late 1980s and early 1990s. There had been challenges to the medical establishment before: they included the short-lived Action Group for Improved Medical Services (Auckland, 1975); the Campaign Against Depo-Provera (Auckland, 1979), which came into conflict with the FPA (one of the main users of this contraceptive); and the Christchurch Patients' Rights Group (1980), prompted by 'the many instances of upsetting and humiliating experiences' women had reported from the main women's hospital in Christchurch. [21] But the Dalkon Shield campaign marked a turning point for Pākehā health groups: it took Fertility Action and THAW into areas of drug regulation, medical discipline, medical misadventure, and the control of drug trials and other research. Patients' rights issues became central because of the difficulty women had in gaining access to their medical files (a necessity for court cases), and because of the many reports from women of poor treatment by medical staff. This work led to the exposure, by Fertility Action members, of an unethical trial related to cervical cancer at National Women's Hospital in Auckland, resulting in the Labour government setting up an inquiry in 1987.

The Cartwright Report and later developments

The subsequent report, known as the Cartwright Report, came out in 1988. Incorporating the findings and recommendations of the presiding judge, Silvia (later Dame Silvia) Cartwright, it became the guiding document and a source of strength and support for many women's health groups over the next five years. [22] It highlighted patients' rights issues, legitimated women's complaints about their treatment within the health system, and validated the importance of their work. For a few years after the inquiry it became easier for women's health groups to have an official voice, via the new area health boards, which were required to consult with their communities.

Important organisational developments also followed. A major women's health conference was organised in Auckland on the first anniversary of the report's release by the Auckland Women's Health Council; this group was formed in 1988 in response to the inquiry and to the establishment of area health boards, as a regional umbrella organisation with a membership of small local health groups and interested women. By 1993 there were 23 such councils or affiliated regional groups, including provincial areas such as Tauranga, Rotorua, Napier, West Coast and Southland; all belonged to the Federation of Women's Health Councils of Aotearoa/New Zealand, launched in 1990. It concentrated on political lobbying, providing consumer representatives on government and other bodies, and policy statements on women's health.

The cervical cancer inquiry and report also encouraged Māori and Pacific groups. Funding, always difficult to obtain in the women's health area, was provided (in the short term) for community-based screening programmes, and many area health boards appointed Māori and Pacific co-ordinators and educators who interpreted their briefs more widely than simply working on cervical screening. Pacific health groups had existed from the mid-1980s, but the inquiry legitimated their concerns, which included the lack of interpreters in hospitals, and the need for educators on health matters to work with church and women's groups in Pacific communities.

The dissolution of elected area health boards in 1991 under the new National government virtually halted the consultative process that had been developing between health authorities and community groups. The proposed implementation of a market model of health-care provision also threatened to undermine the progress that had been made on ethical and patients' rights issues. In the early 1990s, most women's health groups felt under extreme pressure, juggling the needs of individual women clients with lobbying to ensure that a restructured health system would have the capacity to listen to women and provide services meeting their requirements and concerns.

Sandra Coney

1994–2018

A greater emphasis on consumer rights developed after 1993, as a consequence of the Cartwright Report and determined lobbying by women’s organisations. The Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994 established the role of Health and Disability Commissioner, a Code of Consumer Rights, and a consumer advocacy service. The District Health Boards (DHBs) which replaced area health boards also had consumer representatives.

Yet lack of consultation or effective communication was still a recurring problem, giving rise to many of the concerns dealt with by women’s organisations after 1993. Sadly, Sandra Coney’s warning that lobbying would be needed ‘to ensure that a restructured health system will have the capacity to listen to women and provide services meeting their requirements and concerns’ was insufficiently heeded. This was mainly because the reforms introduced a business model in which the government contracted with a range of providers who competed for funding.

The National Advisory Committee on Core Health Services had been established in 1992 to rank health services and advise the Minister of Health on which should be regarded as those ‘to which everyone should have access, on affordable terms and without unreasonable waiting times’. [23] Defining ‘core health’ proved too complex a task, and no such list was developed.

Several major changes to the health system had occurred in 1993, and more followed. The establishment of the Ministry of Health as a streamlined version of the Department of Health resulted in a significant loss of institutional expertise. The Pharmaceutical Management Agency (Pharmac) was created as a Crown Health Enterprise to actively manage government spending on medicines. The Public Health Commission was set up as a separate public health purchasing agency, but was then disestablished in 1995 when it did not align with other aspects of government policy. [24] Under the Health and Disability Services Act 1993, four Regional Health Authorities (RHAs) were established and the 14 Area Health Boards were reconfigured into 23 Crown Health Enterprises (CHEs); but in 1998 the four RHAs were combined to become a single Health Funding Authority, and the 23 CHEs became 24 Hospital and Health Services.

In 2001, after Labour’s return to power, 21 District Health Boards were formed; Pharmac came under the same legislation. In 2002 Primary Health Organisation (PHOs) were developed to manage primary care, including general practice.

In 2010 a Health Quality and Safety Commission (HQSC) was established to advise the Minister, with the aim that it would work with clinicians, providers and consumers to improve health and disability support services. This could have become the ‘go-to’ organisation for women’s health issues; but, apart from the Perinatal and Maternal Mortality Review Committee, women’s health was subsumed in other categories, with no attempt to coordinate all of its aspects. All these changes were meant to improve health outcomes, increase accountability and efficiency, and rein in escalating health expenditure, but they generated much dissatisfaction.

This period saw the growth of a number of single-issue women’s health groups. The Breast Cancer Aotearoa Coalition (BCAC) formed in 2004 as an umbrella organisation representing 32 breast cancer support groups, including Māori and Pacific. By 2018 the Coalition had two additions: Gift of Knowledge, set up in 2010 for women with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer; and Shocking Pink, formed in 2014 for young women with breast cancer. BCAC relied on a mix of public, private and charitable funding, and had a long, varied list of supporters. Competing for funds was another large charity, Breast Cancer Foundation NZ, with mainly corporate sponsors. This organisation was started in 1994 by doctors and had a wider brief than BCAC, including professional education.

Endometriosis New Zealand, started in 1985 as a support group by three women in Palmerston North, became a charitable trust in 1994. With the help of donors such as Pub Charity and Lotteries, it became an example of a small women’s group which transitioned to a large organisation, providing a range of services for the one in ten women and girls suffering from endometriosis. Education programmes were an important component of its work, ranging from schools to medical professionals.

By 2018 the Early Menopause Support Group, started in the 1990s as an email group by a male specialist concerned about the lack of support for patients, was run by women volunteers. Because this condition is less common than endometriosis, the group underwent less expansion.

Mesh Down Under was formed in 2012 to expose problems with surgical mesh used for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Consumer advocacy played an important role in changing professional practice and gaining accident compensation for the affected women. The MOH announced in December 2017 that mesh would no longer be available for this pelvic organ prolaspe after January 2018, but support for those affected was still needed.

Despite the Report of the Cervical Cancer Inquiry 1988, which had been pivotal in raising awareness of how not to treat women and women’s health issues, medical mismanagement of cervical smears re-emerged in Gisborne/Tairāwhiti. After numerous complaints concerning a pathologist and 16 women, in 1999 the government set up a committee to conduct the Gisborne Cervical Cancer Inquiry. Its 2001 report confirmed serious deficiencies not only in the local service, but also in the delivery of the national cervical screening programme. [25]

Two women’s organisations founded in 1988, and involved in both inquiries, were still advocating for women in 2018. The Auckland Women’s Health Council was by then the main contributor to the Federation of Women’s Health Councils (no longer registered as an incorporated society). The Cartwright Collective was a resolutely independent group composed of the original protagonists on behalf of the women affected. It ensured that the key documents relating to the inquiry were available online.

Another organisation formed after the Cartwright Inquiry, the Well Women and Family Trust, like many other groups changed its name as it evolved. In 1989 it was known as WONS (Well Women’s Nursing Service). By 2018 it was giving priority to running free cervical smear clinics in the Auckland area and providing training courses for smear takers. It also belonged to the BCAC.

Although no women’s groups were directly involved, there was also a major advance in the prevention of cervical cancer which would benefit future generations. Research had shown that Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) was the principal cause of cervical cancer. In September 2008 the MOH introduced HPV immunisation for girls and women; in January 2017 this was extended to everyone, male and female, aged nine to 26.

Maternity care changed a great deal over this period. From 1996, women were required to choose one lead maternity carer (LMC) for support during pregnancy, birth and the first six weeks after birth. LMCs received a lump sum for these maternity services. As a result of these funding changes, GPs abandoned maternity care to midwives. Private specialists were less affected because they could charge fees for their private patients, as well as provide specialist care in public hospitals when there were complications. The Maternity Services Consumer Council, a consumer-based organisation made of up 31 community groups with an interest in the provision of maternity care, was registered as a charity in 2008.

Other new organisations providing independent advice on reproductive health formed around issues of postnatal and perinatal distress. The Christchurch-based Postnatal Depression Family/Whanau NZ Trust was established in 2007 by a group of medical professionals and consumers concerned about postnatal and perinatal distress. Perinatal Anxiety and Depression Aotearoa (PADA), formerly Perinatal Mental Health New Zealand, started in Wellington in 2011 to eliminate the stigma around perinatal mental health. The PND Marlborough Charitable Trust was established in 2005. Well Women Franklin, a support group for women with perinatal distress, grew out of a pilot programme conducted by Counties Manukau DHB. Through Blue, formed in Wellington around 2005, provided support for women with depression, not necessarily related to birth. Thrive, a teen pregnancy support trust, was set up in 2010 as a result of the successful Auckland Women’s Centre Teen Parent Project.

Breastfeeding was another maternity-related issue of concern. Numerous breastfeeding networks were publicised through Women’s Health Action. Mother to Mother breast milk sharing started in Christchurch in 2009. The Auckland Women’s Centre set up 26 Weeks for Babies, which coordinated a successful campaign for increased parental leave: the new Labour-led government quickly passed legislation in November 2017 supporting 22 weeks’ leave from 1 July 2018, and 26 weeks’ leave from 1 July 2020, for those who qualified.

Other organisations focusing on mothers’ health and wellbeing began in the 1990s or earlier. TABS (Trauma and Birth Stress) was started in 1998 to support mothers after a stressful delivery, as distinct from postnatal depression; by 2018 it was no longer a registered charity and the website provided information only. Miscarriage Support, beginning in Auckland in 1985, was registered as a charity in 2008. Another support group for parents but led mainly by women, Sands, provided support for Pregnancy, Baby and Infant Loss; in 1986 it had been known as Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Support.

Stuff Limited

Ardas Trebus, left, and Ariane Hollis-Locke of the Christchurch’s Women’s Centre in 2016, when the centre was threatened with closure after 30 years, despite dealing with high demand as a result of the 2010–2011 Canterbury earthquakes. Funding was found and the Centre reopened in 2017.

Other groups offered health-related programmes in addition to a wide range of other support services promoting women’s empowerment and wellbeing. Many of them went back to the 1980s, and had adapted to meet women’s changing needs. As well as those covered in separate entries, the Women’s Centre, a Christchurch community organisation, started in 1986 and reopened in 2017 in new premises, after almost closing down due to the earthquakes (which forced THAW to close). The Wellington Women’s Health Collective, a drop-in centre started in 1987, offered among other things free pregnancy testing, condoms and menstrual cups. The Palmerston North Women’s Health Collective, dating back to 1984, collaborated with many other health organisations in the MidCentral DHB.

Several themes emerge from this overview of women’s health organisations after 1993. First, the contracting-out environment changed the way women’s health groups operated. Public funding meant formal accountability, with performance reviews, annual reports, measurable outcomes and targets to reach. The inevitable power imbalance bred mistrust. Advocacy groups were particularly disadvantaged. However, some organisations, such as Family Planning, did flourish in the new environment.

Commercial and corporate sponsorship helped many organisations grow, but this could be at the expense of core values. The success of this co-operation depended on the alignment of goals. Organisations often existed with a complex mix of public/private/charitable funding which could be time-consuming to manage and sustain. Being a registered charity also involved duties and responsibilities. From 2005 a Charities Commission oversaw the registration of charities, with the aim of ensuring their validity and good governance. Charitable fundraising using the internet became an accepted source of income.

Meanwhile the medicalisation of well-women care increased, especially in childbirth, contraception and sexual health. Sometimes this provided a perceived benefit; for example, in 2001 medical abortion, as opposed to surgical abortion, became an option for New Zealand women, with the required drug, mifepristone, imported by a not-for-profit company, Istar Ltd. This enabled Family Planning to introduce a new medical abortion service in one of its clinics. At other times medicalisation carried greater risks; for example, the World Health Organisation recommended a caesarean section rate of between 10 and 15 per cent, but in New Zealand by 2015, the rate was 25.5 per cent. [26]

Women’s Health Action advocated for natural birth and also for breastfeeding. Natural treatments for menopausal symptoms were also advocated by Women’s Health Action and other groups, especially after a large menopause treatment trial in the USA was stopped in 2002 because hormonal therapy was linked to an increased risk of stroke, heart attack and breast cancer. The risks and benefits of hormonal treatment were still under review in 2018. Also under review was the 1977 abortion legislation, with the government exploring options for removing abortion from the Crimes Act and making it a women’s health matter.

Some professional organisations, such as the New Zealand Nurses Organisation and the New Zealand College of Midwives, took up women’s health issues, However, most medical professional organisations incorporated women’s health into general health, for example in fields such as heart disease, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, immune disorders, diabetes, and osteoporosis. These conditions all affected women significantly but not exclusively, and attracted public funding.

Volunteering of all kinds became less evident between the 1990s and the 2010s, as more women were in demanding paid employment as well as caring for others in the home. Moreover, many organisations in the not-for-profit sector became or were forced to become more professional and less dependent on volunteers. The market-driven ethos affected some of the passion for volunteer work in the area of women’s health.

Finally, the powerful influence of the internet completely changed the way groups communicated. The groups mentioned above all had their own website or Facebook page, or were listed by coordinating groups such as Women’s Health Action or the BCAC. Many communicated via email, Facebook, blogs, newsletters and chat groups. Other groups masqueraded as ‘women’s support groups’ but were in fact commercial ventures. Some groups existed solely online. Personal one-to-one or group contact was still valued, but was less evident.

In 2001 the Labour-led government, under Prime Minister Helen Clark, recognised the tension between the state and the voluntary sector, and issued a Statement of Government Intentions for an Improved Community-Government Relationship. The statement promised ‘a future where the state performs its role as a facilitator of a strong civil society based on respectful relationships between government and community, voluntary and iwi/Māori organisations’. [27]

This was followed in 2003 by the establishment of an Office for the Community and Voluntary Sector, providing a channel for information-sharing and co-ordination between government departments and the non-profit sector. It was administered by the Ministry of Social Development until February 2011, when it became part of the Department of Internal Affairs. In the absence of large-scale philanthropic foundations in New Zealand, government assistance for community health organisations would clearly be needed in the foreseeable future, but further changes and tensions were inevitable.

Margaret Sparrow

Notes

[1] See White Ribbon, June 1897, p. 11.

[2] New Zealand Mail, 7 December 1894.

[3] White Ribbon, November 1901, p. 11.

[4] See, for example, White Ribbon, September 1898, p. 11; August 1903, p. 11.

[5] Christchurch Press, 3 December 1892.

[6] White Ribbon, December 1902, p. 11.

[7] See AJHR, Vol. 3, H-31, 1902, p. 64.

[8] Anna Stout, 'The New Woman', Citizen, December 1895, p. 153.

[9] Canterbury Times, 11 April 1895.

[10] See, for example, Dr W.A. Chappie, The fertility of the unfit, Whitcombe & Tombs, Christchurch, 1903; also the views of Dr MacGregor, Inspector of Hospitals, AJHR, H-22, 1897, p. 1.

[11] See Nina Barrer Papers, ATL.

[12] For one expression of this, see AJHR, Vol. III,, H-31, 1937–38, pp. 9–10.

[13] AJHR, Vol. II, H-31 A, 1937–38, p. 18.

[14] See Barbara Brookes, 'Housewives' Depression: The Debate over Abortion and Birth Control in the 1930s', NZJH, Vol. 15 No. 2, 1981, pp. 117–18.

[15] Pamphlet, c. 1940, Ephemera Collection, ATL.

[16] Auckland Weekly News, 3 April 1902, p. 12.

[17] Health and Beauty News, April 1939, p. 1.

[18] See, for example, Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, Complaints and disorders: the sexual politics of sickness, Writers and Readers Publishing Co-operative, London, 1973.

[19] See Sandra Coney, 'From Here to Maternity', Broadsheet, No. 123, October 1984, pp. 4–6.

[20] Elizabeth Rehu Murchie, Rapuora: health and Māori women, Te Rōpu Wāhine Māori Toko i te Ora [Māori Women's Welfare League],

[21] Broadsheet, No. 95, December 1981, pp. 22–23.

[22] Committee of Inquiry into Allegations Concerning the Treatment of Cervical Cancer at National Women’s Hospital and into Other Related Matters, The report of the cervical cancer inquiry, 1988, Government Printing Office, Auckland, 1988. https://www.moh.govt.nz/notebook/nbbooks.nsf/0/64D0EE19BA628E4FCC256E450001CC21/$file/The%20Cartwright%20Inquiry%201988.pdf

[23] Minister of Health, the Hon. Simon Upton, Your health and the public health [Green and White paper], Government Print, Wellington, July 1991.

[24] For an account of how and why the Public Health Commission was dismantled, and the roles played by industry lobbyists, see David Skegg, The health of the people, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2019.

[25] See Duffy, A.P. et al., Report of the ministerial inquiry into the under-reporting of cervical smear abnormalities in the Gisborne region [April 2001]. http://www.moh.govt.nz/notebook/nbbooks.nsf/0/a79b9e52f04d57e5cc256a9f006f1687/$FILE/csireport.pdf

[26] In 2015, only one in three women giving birth had what was classed as a normal birth. See Ministry of Health, ‘Report on Maternity’, https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/report-maternity-2015

[27] Steve Maharey, ‘Improving the Community - Government Relationship’, 4 December 2001. Retrieved 25 October from https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/improving-community-government-relationship

Unpublished sources

Fleming, P. J., 'Eugenics in New Zealand 1900–1940', MA thesis, Massey University, 1981

Griffiths, Shelley, 'Feminism and the Ideology of Motherhood in New Zealand, 1986–1930', MA thesis, University of Otago, 1984

O'Donnell, Jean-Marie, 'Female Complaints: Women's Health in Dunedin 1885–1910', MA thesis, University of Otago, 1991

Parkes, Charlotte, 'Silent Labour: Women's experience of childbirth in Auckland 1920–1940', MA thesis, University of Auckland, 1992

Published sources

Bird, Christine, 'Health Alternatives for Women', Race, Gender, Class, No. 4, December 1986, pp. 5–9.

Boston Women's Health Book Collective, Our bodies, ourselves, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1971

Brookes, Barbara, 'Reproductive Rights: The Debate Over Abortion and Birth Control in the 1930s', in Brookes, B., Macdonald, C. and Tennant, M. (eds), Women in history: essays on European women in New Zealand, Allen & Unwin/Port Nicholson Press, Wellington, 1986, pp. 119–36

Bryder, Linda (ed.), A healthy country: essays on the social history of medicine in New Zealand, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 1991

Bunkle, Phillida, Second opinion, Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1988

Calvert, Sarah, 'Knowledge is Power: Reasons for the Women's Health Movement', Broadsheet, No. 80, June 1980, pp. 26–30

Calvert, Sarah, Healthy women, New Women's Press, Auckland, 1982

Committee of Inquiry into Allegations Concerning the Treatment of Cervical Cancer at National Women’s Hospital and into Other Related Matters, The report of the cervical cancer inquiry, 1988 [The Cartwright Report], Government Printing Office, Auckland, July 1988. https://www.moh.govt.nz/notebook/nbbooks.nsf/0/64D0EE19BA628E4FCC256E450001CC21/$file/The%20Cartwright%20Inquiry%201988.pdf

Coney, Sandra, The unfortunate experiment: the full story behind the inquiry into cervical cancer treatment, Penguin NZ,

Coney, Sandra, 'A Living Laboratory: The New Zealand Connection in the Marketing of Depo-Provera', and 'The Exploitation of Fear: Hormone Replacement Therapy and Menopausal Women' in Peter Davis (ed.), For health or profit?, Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1992, pp. 119–43, 179–207

Coney, Sandra, Standing in the sunshine: a history of New Zealand women since they won the vote, Viking/Penguin NZ Ltd, Auckland, 1993

Coney, Sandra, Unfinished business: what happened to the Cartwright report?, Women's Health Action,

Fenwick, Penny, and Margaret McKenzie, 'How Helpful is Self-Help?' Broadsheet, No. 68, April 1979, pp. 24–27

Gordon, Doris, Backblocks baby-doctor, Faber & Faber, London, 1960

Manson, Cecil and Celia, Doctor Agnes Bennett, Michael Joseph and Whitcombe & Tombs, London and New Zealand, 1960

Maxwell, Margaret (ed.), Women doctors in New Zealand: an historical perspective 1921–1986, IMS (NZ), Auckland, 1990

Mein Smith, Philippa, Maternity in dispute, New Zealand 1920–1939, Historical Branch, Department of Internal Affairs, 1986