This essay written by Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku, Shirley Tamihana, Julie Glamuzina and Alison Laurie was first published in Women together: a history of women's organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Alison Laurie, Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku and Julie Glamuzina in 2018.

Formal lesbian organising in Aotearoa/New Zealand began in the 1970s. Lesbians faced discrimination and hostility if they were open about their sexuality and chosen way of life, at least as far as the mainstream Pākehā culture was concerned. [1]

The various informal groups and networks which existed prior to the 1970s may be seen as emerging from contacts between individual women. Before the Second World War, lesbians found it difficult even to meet each other, let alone organise. The only ways groups could form were through employment, under the cover of a common interest such as sports or drama, or through working for political goals such as suffrage and temperance. It is almost impossible to obtain information about such groups, especially if no oral sources now exist, and tracing them is beyond the capacity of this essay. Until at least the 1960s, lesbian groups were obliged to pretend to be something other than they were, even if all the members were aware and conscious of their lesbian identification.

The situation improved as a result of the liberation movements of the early 1970s. Lesbians grouped to establish social networks which would provide support and friendship in a hostile society, venues where women could socialise safely and be open in their lives without fear of violence or abuse, and the opportunity to work for social change. However, many of the earlier problems remained, and anti-lesbian attitudes and outright attacks made it difficult for these groups to operate. Until the late 1970s, newspapers refused to carry advertisements for lesbian groups or events, and telephone listings were denied. Access to venues was problematic. Women leaving known lesbian clubs and venues could be physically or verbally attacked, and lesbians demonstrating publicly risked arrest and hostility. It is not surprising, then, that many lesbians did not want to be involved in formal, overtly lesbian groups.

This section discusses a representative range of groups and networks up to 1993. It includes separate entries only for groups and organisations which clearly identified themselves as lesbian. By 1993, the range of organisations was broad – from small, often informal groups which met to develop political theory, provide support or work on a specific project, to larger, more formal groups. Their agendas included health and welfare issues, cultural and sporting activities, as well as specific political, social and economic goals. For a variety of reasons, many formal lesbian groups were short-lived.

Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku and Shirley Tamihana describe Māori lesbian organising in particular detail. Māori lesbians were active in almost every group and network discussed here. Non-Māori lesbians included women of various ethnicities – Chinese, Dutch, English, German, Indian, Pacific Islands and those with origins in the territories of the former Yugoslavia, for example; and together these groups included lesbians of different classes, ages, abilities and interests.

Maori lesbians

Taku hiahia e kare

Kia awhi ai taua

Kia puawai nga wawata

Te aroha

E te tau, e [2]

The existence of Māori lesbians in pre-European times has been confirmed from a number of sources. The Royal Commission on Social Policy stated in 1988 that:

Of specific concern to Māori lesbians however is the claim sometimes made that homosexuality was introduced by Pākehā and that it had no place in traditional Māori society. There is no evidence to support this claim. Kuia and Kaumatua have suggested to the Commission that on the contrary homosexuality – female and male – was not uncommon in pre-European times and that it was in fact more readily accepted than today. [3]

Telling the story of Māori lesbian groups in Aotearoa brings up many memories; focuses on the faces of many personalities long since gone. What makes up a group? Or an organisation? Is it a gathering of people for a specific task or purpose, with a shared goal? Ours was simply survival.

Within the rural community, before the migration to work in the city, androgynous figures, usually in plus-fours heaving a shovel, or sweating black-singleted in the shearing shed, were not uncommon. They were simply there; they laughed and often loved; they despaired too, and, of course, they died. They left a legacy of intriguing stories, and more than a few broken hearts. Often, with a more feminine partner who was sometimes the biological mother, but more usually a biological aunt, they raised children – generations of them. And they contributed hugely to the whānau, and marae community, in a variety of ways. They were simply there; they were valued, for what they brought; but their sexuality, their lesbianism, was generally unnoticed, and if noticed, then seldom discussed. It was simply not good form. Yet that is not the same as saying they were invisible, because they most certainly were not.

From the 1940s onwards, the move to the towns, away from the comfort and security of whānau support and kinship networks, brought huge changes. Occupational ghettoes formed, in hospital laundries and support services, the post office and tolls exchange, psychiatric nursing or van driving – all jobs that guaranteed, often for the first time, solid financial security.

Groups congregated at certain hotels, or met in private homes. In Auckland, a network of sportswomen and their supporters emerged – playing softball in summer, darts and eight-ball in winter, holding regular, well-watered card evenings in garages and rumpus rooms throughout the suburbs. In Wellington, a specific group of kamp Māori women were meeting in the 1960s. And of course on the ships, a staunch sorority of Māori lesbian women looked after their femmes, watched out for themselves, and led a rather vigorous life.

By 1970, with a buoyant economy and plenty of money around, the stage was set for a more organised social environment. Pubs such as the Alex in Parnell (site of Mary's Bar), Gleeson's in Auckland, and the Bistro in Wellington, welcomed kamp (gay or lesbian) trade. But in winter 1971, a small group of Auckland women, brought together by a young Auckland hospital haemotology technician, met to plan a social club. This group included a sixties-plus retired dancer, a famous artist/film producer, and three Māori women – two ex-armed services, the third a student. The club was to be called the Phoenix Society. Its first function was held in the university arts centre in Grafton Road; it was a night to remember, with big butch Māori bouncers, and a singularly Māori presence everywhere. After a few more evenings, energy drained away, and the main organiser suddenly went to Australia, leaving behind a withdrawal to private homes and hotel bars again – until the founding, in the summer of 1971-72, of the KG Club, at the Symonds Street end of Karangahape Road.

The original KG Club was essentially a working-class women's environment, with a strong Māori presence; feminists, 'women's libbers' and middle class 'snobs' were viewed with some suspicion. They were accepted only if they could 'hold their own' – usually at the pool table or the dart board. By the time of the shift to Hereford Street, the club had become primarily a venue for middle-class Pākehā feminists. As the 1980s began, the Māori lesbians regrouped in private homes, eight-ball clubs, the refuge movement, indoor cultural groups, basketball teams, kōhanga reo, and other venues.

The early 1980s was a period of dynamic change. Māori lesbian social and political activity remained beneath the wider umbrella of tribal or pan-tribal networks. Although lesbian women would get together and work on specific issues or tasks at events such as the Springbok tour protests, the Tuhoe Festival, Te Huinga Rangatahi (Maori Tertiary Students Association), the Kingitanga Coronation Celebrations, Bastion Point, women's haka competitions, or the Young Māori Leadership Conferences, there was no coordinated organisation as such. With the emergence of a strong Māori force for self-determination in groups such as the Nga Tamatoa movement and Te Reo Maori Society, most Māori energy, lesbian or otherwise, was being channelled into the land and language struggles.

Small enclaves would meet in Arawa, Tūhoe and Waikato. Discussions centred on issues such as kawa or gendered protocol issues, women's knowledge, waiata or song, health, karanga or women’s chant, and education. These informal study groups, occasionally facilitated by the University of Waikato's Continuing Education Centre, responded to a perceived interest, then withdrew. As with previous groups, the kaupapa was primarily to support and sustain each other, give each other strength, and learn how to help the younger ones, by drawing wisdom and knowledge from tribal roots, and from rural and iwi backgrounds. There was little hard-core analysis; most of the women came from the country, from the marae, as lesbians and as Māori. Particularly with the older women, there was a very strong sense of tribal identity, and also considerable fluency in the Māori language. Because of this, the participating women maintained contact with each other, socially or through tribal events.

Meanwhile in Auckland, a series of Māori lesbian/bisexual women's groups and activities were surfacing from an entirely different place – well-educated (in western terms), urbanised, young, articulate, often tribally dislocated women. Over a 10-year period, beginning with a hui on Waiheke, a Black Dykes organisation was formed among interested women in the three largest cities. Codes were extremely strict, and rigidly observed; the ideological basis or kaupapa appeared to be derived primarily from Black American and Marxist sources, within a structural analysis framework. There was extensive liaison with heterosexual women and with men, observing a specific political agenda. Membership included Pacific Islands women, and women of colour. Racism and Māori nationalism became the priority issues. Contact with the older, more established, Māori-speaking lesbian network was minimal; meanwhile, the informal study groups in the tribal environment sturdily laboured on.

Toward the end of the 1980s, the Black Dyke consciousness had mellowed into a more tribally focused entity that proclaimed itself 'Wāhine mo ngā Wāhine'. At this point, some of the older women became involved, although a complete merging of the earlier, 'non-political' group with the urbanised group had yet to occur. In 1989, after the Easter Lesbian/Gay Conference at Waipapa marae in Auckland, a large group socialised together, and lively discussions followed between the over-45 veterans of the pool table and pub culture, and the younger, more political generation.

Sporadic hui, held in Auckland, Wellington, Rotorua, and Christchurch, continued to reflect a nationwide need to get together, for support, social contact, and self-esteem. Other networks – from the health sector, education, visual and performing arts, and women's refuge – were also involved. They undertook their own fundraising, with some contribution from other agencies. Members also travelled to indigenous women's and lesbians' events in Australia.

In the late 1980s the Māori word takatapui or takatapuhi, 'beloved and intimate friend of the same gender', was recognised and celebrated by Māori lesbians and gays; and in 1989, this loose grouping assumed the name Wāhine Takatapui Māori o Aotearoa, abbreviated to Wāhine Takatapui.

Early groups

There are few written sources of information about lesbian individuals or groups before the 1970s. However, some of the settler women who arrived in the nineteenth century passed as men, in order to marry other women and to live their lives more freely by gaining access to male employment opportunities such as goldmining. Other means of independent economic survival for women were limited. Single women could live together and support themselves while working in occupations such as domestic service, especially in hotel or hospital settings. Among the upper and middle classes, romantic friendships of a passionate and committed nature, some of which were undoubtedly sexual, occurred between both married and unmarried women. Research into similar settler societies elsewhere has documented the existence of lesbians in all these situations.

Lesbian and gay groups socialised openly from the 1890s in Germany and some other European countries. Some lesbians who were able to travel may have left New Zealand and moved overseas, where the opportunities to live openly and meet other lesbians were greater – for example at The Cave of the Golden Calf, a London nightclub patronised by lesbians, which Katherine Mansfield frequented. The First World War brought large numbers of women together in work situations, making it easier to form lesbian relationships and establish informal networks.

The 1920s has been described as a flamboyant and exciting period in large metropolitan centres such as New York, London, Paris and Berlin. Various sources describe the lively lesbian and male homosexual meeting places and nightclubs in those cities. There were no similarly known venues here.

Nonetheless, groups and networks of lesbians by then existed here, at least in the main centres. Two women could live together without occasioning comment; providing they were discreet, they were not regarded as lesbian and could live without harassment. The poet Ursula Bethell and her companion Effie Pollen, for example, lived together for many years until Effie's death, had many friends, and were not socially ostracised.

During the Second World War, as in the First, many women again found it easier to be financially and socially independent, to form lesbian relationships and to establish networks. However, social ostracism, discrimination and direct persecution meant that throughout the first half of the twentieth century, many lesbians were afraid of discovery by the heterosexual majority.

In the post-war years a number of formal groups and organisations formed overseas. Most were mixed lesbian and gay, and were male-dominated, but some separate lesbian groups did exist: the Daughters of Bilitis started in the USA in 1955, and the Minorities Research Group began in 1962 in Britain. Even then, however, they chose ambiguous names. New Zealand lesbians who might have organised similar groups here went overseas; at least four New Zealanders were prominently involved in organising the Minorities Research Group's activities during the 1960s.

In New Zealand, rapidly increasing urbanisation during the post-war period meant that by the late 1950s there were numbers of self-identified Māori lesbians and gay men in Auckland and Wellington in particular. Some non-Māori lesbians, mainly working-class women, were a part of these circles. City life meant anonymity and freedom from oversight by family and neighbours. Women in female-intensive, live-in occupations, such as nursing and domestic service in hospitals and hotels, continued to have the opportunity to form relationships, and many networks developed in these areas. Teachers too formed networks of individuals and couples. 'Going flatting' was not common for younger women in the 1950s, but same-sex hostel accommodation was acceptable, allowing networks to take shape. Lesbian networks and friendship circles also expanded through the New Zealand armed forces despite regulations banning homosexual behaviour. [5]

From 1919 New Zealand liquor licensing laws required pubs to close at 6 pm, and prohibited food, entertainment or regular seating in public bars. There were very few pubs where women could meet, as after 1911 women could be served only in special ladies’ and escorts bars, not provided in many pubs. In later years, coffee bars were an alternative. The Ca d’Oro, in Customs Street, Auckland, opened in 1957, was a meeting place for some gay men and lesbians, as was the Tete a Tete in Wellington. From about 1962 onwards, in Wellington, a Pākehā and Māori lesbian group met in the Bistro Bar of the Royal Oak Tavern, and sometimes in the upstairs lounge bar of the Western Park Hotel. This group attempted to gain membership of the gay men's Dorian Society when it formed in 1963, but was unsuccessful until 1970. Some individuals ran advertisements in a local newspaper for a Radclyffe Hall Memorial Society, and met more lesbians in this way. Informal groups met socially for parties (often together with gay men, especially 'drag-queens'); because they were visible, they provided new opportunities for lesbians to make contact. In Christchurch a lesbian group met at the British Hotel in Lyttelton as early as the late 1950s, and from the 1960s at the Gresham Hotel in Cashel Street, Christchurch. In Auckland, from the 1960s, groups of lesbians often met at the Queen's Ferry Hotel, the Occidental Hotel, the 'Alex' (Alexandra) in Parnell and, later, the Shakespeare Hotel.

From 1967 the extension of licensing laws allowing pubs to close at 10 pm and the setting up of lounge bars in many pubs provided more opportunities for women to meet publicly. Alcohol and drinking in pubs became important features of lesbian social life. Unlike heterosexual women's groups, lesbians had few alternatives. Many lesbians felt alienated from mainstream heterosexual society and the prescribed feminine roles of the time. Drinking and smoking were experienced as aspects of claiming masculine privileges and freedoms. They were also responses to a hostile and repressive heterosexual society. Also drinking in the few hotels which tolerated the presence of lesbians were prostitutes, criminals, and a whole class of marginalised people. Unlike male homosexuality, lesbianism was not actually illegal, but many lesbians felt like criminals and they were frequently treated as if they were criminals. The police sometimes raided private parties, harassed lesbians in public bars, and noted licence plate numbers of cars parked outside known lesbian venues.

Apart from these visible semi-public groups, others, particularly networks of middle-class Pākehā women, fearful of being exposed as lesbians, met in private homes. Their fears were entirely appropriate. Older lesbians could easily lose their employment, their accommodation, and their relationships with families, friends and neighbours if their lesbianism was revealed. Younger lesbians whose parents 'found out' about them were sometimes subjected to medical treatment, which could involve involuntary committal in a psychiatric institution for electro-shock treatment and aversion 'therapy'. [6] Other young lesbians risked being defined as juvenile delinquents, labelled 'out of control', and placed under supervision. Although the majority did not suffer such extreme consequences, a few examples were enough to keep lesbians afraid and compliant. Even as late as the 1970s, these mechanisms were sufficiently effective to keep lesbians reluctant to organise openly. The majority of self-identified lesbians remained isolated and largely invisible, even to one another.

A new era in organising

The late 1960s brought an explosion of new ideas and movements, particularly from the USA. Black liberation and civil rights issues, opposition to the Vietnam War, drugs and the hippie culture, with its emphasis on personal freedom, all played a role in changing attitudes and consciousness. New Zealand society became less rigid and conformist. Widespread secondary education in the post-war period, the affluent society, and the large numbers of post-war 'baby-boomers' becoming young adults disrupted a conservative and repressive culture. New possibilities, options and ideas emerged.

By the early 1970s, a new era in lesbian organising had begun. Three influences helped to make this possible. The first came from the older visible lesbian communities: largely Māori and working class, these had developed strong networks in the major centres. The second was the impact of women's liberation. Lesbians were among the many women active in the movement; other women became aware, as they worked on deconstructing rigidly defined gender roles, that 'coming out' as a lesbian was now a possibility for them. Though lesbians from both these strands later left women's liberation groups, alienated by anti-lesbian attitudes and wanting to focus on lesbian concerns, others remained.

The third influence was the Gay Liberation Movement. The New York Stonewall riots of 28 June 1969 sparked what has been called a powder trail which had been laid throughout the 1960s. [7] That night the visible lesbians and gay men who frequented the Stonewall Bar in Greenwich Village, New York, fought back against the police when the bar was raided. Gay and lesbian activists were able to use these events to publicise the new ideas of gay liberation. Within days the Gay Liberation Movement had been formed; branches spread around the USA, then the world, within the following year.

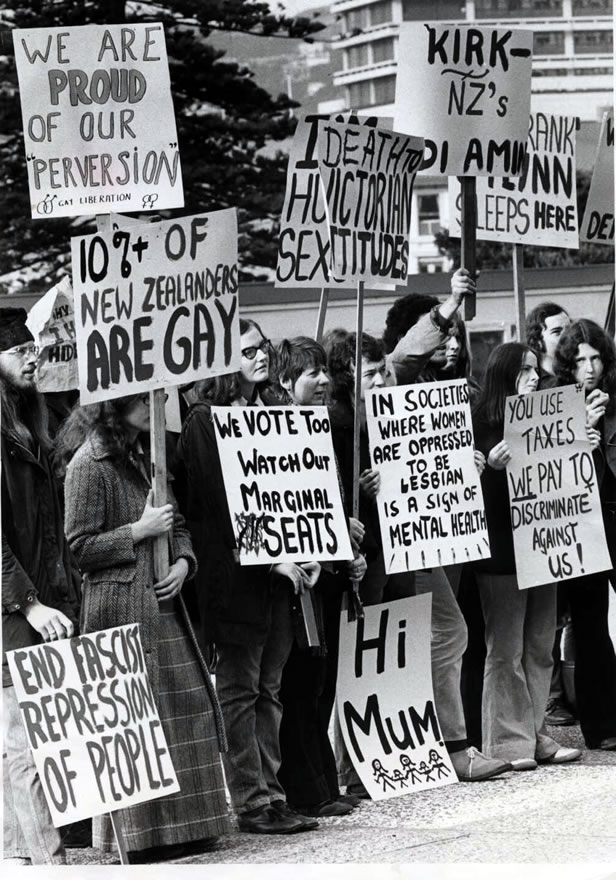

Gay Liberation was started here in 1972 by Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku and five others at the University of Auckland. Later many lesbians left to form lesbian-only groups; they found that the sexism of the men, with their differing goals and agendas, made co-operation difficult. Others, such as Rae Dellaca in Wellington, continued to work in the mixed Gay Liberation groups. In rural areas lesbians co-operated more closely with gay men, and for a longer period, because of their small numbers and the isolation of their communities.

Alexander Turnbull Library, PAColl-7327.

Lesbians taking part in the Gay Liberation Movement protest outside Parliament in 1974.

The first lesbian organisation of the 1970s was Auckland's KG Club – the Karangahape Road Girls' Club, or the Kamp Girls' Club. While its purpose was to provide a private social space for lesbians, its very existence represented a bold political act – an expression of a self-conscious lesbian community. In the next few years, small political and support groups formed in Auckland: in March 1974, for example, the Gay Feminist Collective started as a breakaway group from Gay Liberation, and throughout 1977 and early 1978, a collective discussed theory and produced Juno newsletter.

In Christchurch and Wellington, the first autonomous lesbian political organisation, Sisters for Homophile Equality (SHE), formed in 1973. SHE was an important development. The communities it arose from, and was sustained by, changed as a result of its wide range of activities. Lesbians' views of themselves changed too, as they shared their experiences and developed analyses of patriarchy and heterosexism. Club 41, started and owned by four members of Wellington SHE, Porleen Simmonds, Marilyn Johnston, Liz Hutton and Jan MacFarlane, was the forerunner of a number of collectively run Wellington lesbian clubs. Wellington SHE's tenacity in persisting with projects such as Circle magazine, and in keeping the interests of lesbians to the fore despite opposition and ridicule, strongly influenced the character of the developing lesbian communities there. A staunch lesbian consciousness and awareness persisted into the 1990s, despite political shifts.

The first feminist printing press in Aotearoa, Herstory Press (1974-80), was started in Wellington by Jill Hannah and Robyn Sivewright. It developed communication links among lesbians, printing many feminist and lesbian publications, including Circle, and distributing lesbian books from the USA. In April 1977 the radical lesbian feminist theory group, Lesbians Ignite Fire Brigade, began regular theory meetings. This small but influential group was responsible for several protests during 1977, and presented significant papers on lesbian feminist politics at the Piha Radical Feminist Caucus (1978). [8]

There were conflicts between lesbians and straight feminists at Piha and at the United Women's Conventions (1977 and 1979); after each of these, more lesbians began to organise separately. Like SHE, these groups had a self-consciously lesbian agenda and organisation. In 1978 several groups were formed in Wellington; they included a working-class group, a self-help therapy group and the Lesbian Project, which focused on organising regular social events and raising funds to open a lesbian centre. Breathing Space, a discussion and social group for women who were 'coming out' as lesbians, held regular fortnightly meetings during 1979 and 1980. The Wellington Lesbian Network, formed following the April 1979 United Women's Convention, met at regular intervals, organised many political and social events, and produced a newsletter.

In November 1979, the first Lesbian Centre opened in rooms in Boulcott Street, sublet from premises rented by the Women's Resource Centre. The actions organised from the centre included street marches, Lesbian Liberation Week (October 1980), a campaign against the Wellington City Council, which had refused to carry advertisements for the centre on its buses, and a campaign for inclusion of lesbians and gay men in the Human Rights Commission Act 1977. In 1982 another Lesbian Centre was started in upper Cuba Street, as part of a complex which included the Women's Place Bookshop and tearooms.

Other main centres had their own distinctive forms of organising. In smaller centres, lesbians usually worked in organisations with feminists, or with gay men, for mutual support in both political and social activities – for example in MAGRA (Manawatu Gay Rights Association), established in Palmerston North in 1977. Individuals acted as contacts in smaller centres; in 1980, for example, Circle listed contacts for Ashburton, Gisborne, Wanganui and Wairarapa.

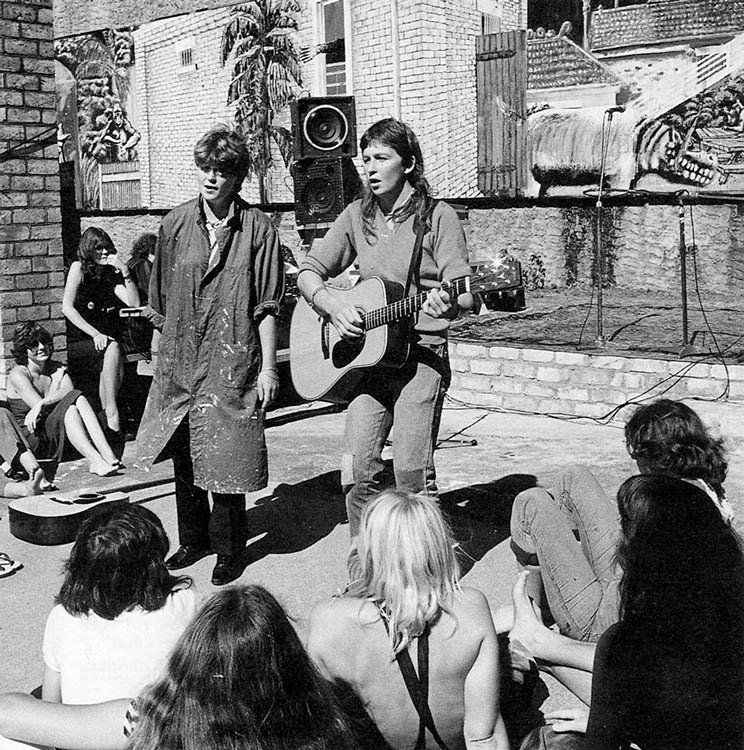

Gill Hanly

The Topp Twins, muscians who have become internationally successful, performing at a women’s concert held at Outreach, Auckland, in 1982.

During the 1980s groups and organisations grew in numbers and scope, as lesbian communities became more open. Political activities became more organised, and publications and services expanded.

Lesbian phone lines were started on a regular basis in various cities in the 1980s. Phone services have always been extremely important for lesbians; they enable women becoming aware of their feelings for other women to seek information and support cautiously and anonymously, sometimes years before they feel ready to join a lesbian community. Early in 1981 a Christchurch group established a 'lesbian line' telephone service; a similar service was set up in Wellington in 1983, and in Dunedin and Timaru in 1984. By 1990 services operated in Nelson, Palmerston North, Timaru, Wanganui and Hamilton, as well as the four main centres.

Lesbian radio broadcasting started in Wellington on Access Radio, followed by Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin. The Christchurch programme, Wāhine Takatapui/Soundwomen, broadcast on Plains Radio FM; Dunedin used the student radio station. Radio has been a way to disseminate information and ideas and promote discussion through many sections of the lesbian communities.

During the early 1980s, several lesbian newsletters or magazines were produced, including Behind Enemy Lines (1981), Dykenews (Auckland, from 1982), Lesbian Lip (Wellington, 1982), and Glad Rag (Wellington, 1983). Hamilton lesbians produced a magazine in 1980; Dunedin had a monthly newsletter, Against All Odds (1985-86). As was the case overseas, such publications were enormously important for lesbian community development. For isolated and closeted lesbians in particular, receiving a magazine or newsletter helped them feel that they were part of a wider community. This was also true for all lesbians who wished to keep up with the development of ideas, theory, actions and campaigns elsewhere. Little of this information was available through the mainstream press, or even through feminist magazines. Lesbian publications, like those of other women's interest groups such as temperance and suffrage, often functioned as organisations in their own right, with a loyal and active readership.

Education was another important area of activity. Lesbian studies courses were offered through the WEA in Auckland and Wellington, through Continuing Education and Women's Studies at Victoria University of Wellington, and through Nelson Polytechnic. Although not directly involved in running these courses, the Lesbian Caucus of the New Zealand Women's Studies Association, formed at Blenheim in 1984, served as a support for such initiatives.

Lesbian writers and artists became more organised from the mid-1970s. Members of Christchurch SHE were also active in the women's art movement, and in the expansion of women's literature. Wellington's Women's Gallery was supported by many lesbians and was an important venue for the expression of lesbian culture. A Hamilton-based lesbian writers' group, Scratching the Surface, began in 1990; its core group involved 10 to 15 Māori and Pākehā writers of varying ages and class backgrounds, contributing to a steadily growing volume of local lesbian fiction and non-fiction.

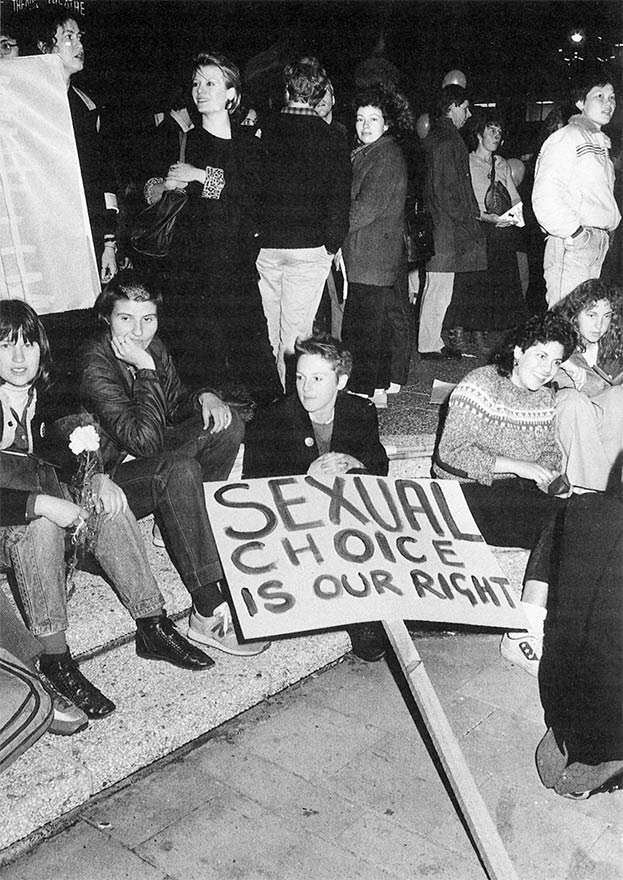

Gill Hanly.

Women gathering for a rally in support of the Homosexual Law Reform Bill in Aotea Square, Auckland, 1985.

Lesbian organisations were a significant force in the struggle for homosexual law reform. [9] Although lesbianism has never been a criminal offence in this country, the criminalisation of male homosexuality up until 1986 had strong implications for lesbians. After Fran Wilde MP introduced the Homosexual Law Reform Bill in 1985, some lesbians worked with gay men in organisations such as the Gay Task Force and the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, or in coalitions with heterosexuals, such as the Coalition for the Bill. Others formed separate organisations, such as the Lesbian Coalition in Wellington and Auckland, and took action against the petition opposing the bill. However, the relationship between lesbians and gay men was difficult, with Pākehā gay men's support for lesbian feminist and anti-racist initiatives remaining insubstantial.

The first national lesbian conference was organised by SHE in Wellington in March 1974; two others followed, in 1975 and 1978. Through the 1980s several more national and regional gatherings were held, including the Auckland Lesbian Festival (1986). Some were initiated by Lesbian Alcohol and Drug Action (LADA, formed in 1985) to focus on health and addiction. The Lesbian Caucus of the women's refuge movement also held its own national meetings to discuss violence in the lesbian community. Representatives from New Zealand attended international conferences and gatherings, particularly for the International Lesbian Information Service, and the International Lesbian and Gay Association, which included member organisations from over 30 countries. From 1986, the Ministry of Women's Affairs funded a number of consultations with representative groups of lesbians, ranging from issues as broad as pornography and broadcasting policy, to those of specific concern to lesbian groups with regard to child custody, immigration, next-of-kin, health policy, and disability. [10]

Lesbians of Colour (with members mainly of Pacific Islands and Asian descent) were active too, particularly in Wellington. By the early 1990s, lesbian occupational groups were widespread. Lesbians in the Public Service, formed in Wellington in 1988, met regularly; also active was the Lesbian Caucus of the Equal Employment Opportunities Practitioners Association. Similar groups existed among primary, secondary and tertiary teachers. In some years, including 1986, 1988 and 1993, national combined Lesbians and Gay Men in Education conferences were held.

In the 1990s new groups continued to form, for example at the Whanganui, Hutt Valley and Kapiti Women's Centres. In Wellington, the Overland and Cafe Club arranged outdoor walks and tramps; in Christchurch, groups met to learn ballroom dancing. Young lesbians organised with young gay men, for example in the Association of Lesbian and Gay Youth (ALGY) in Auckland, and held national conferences. In Wellington (1988) and Christchurch (1990), Lesbian Action for Visibility (LAVA) groups were formed to focus on political issues, particularly human rights legislation. The wording put forward by MP Katherine O'Regan in an amendment to the 1993 Human Rights Bill, which would add 'sexual orientation' to unlawful grounds of discrimination, specifically mentioned lesbians.

In Auckland, a collective organised an annual Lesbian Ball from 1983, regularly attracting over 700. The proceeds funded the Lesbian Education and Support Organisation, which by 1993 had run support groups and other services for 12 years. Another Auckland group, Proud Older Lesbians Like You (POLLY), organised social events and discussions for older lesbians. Regular mixed lesbian and gay conferences were held, for example at Carrington Polytechnic in 1989; opened by a lesbian Māori, this had a particular anti-racism focus. From 1981, anti-racism work became a strong feature of the lesbian movement.

Looking back from the perspective of 1993, many lesbians believed that the gains of the mid-1960s to late 1980s would need to be defended. A harsh economic climate was resulting in the return of earlier fears. For the lesbian community, such circumstances made organising more important than ever.

Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku, Shirley Tamihana, Julie Glamuzina and Alison Laurie

1994-2018

After 1993, as would be expected, there were many changes in lesbian organising, some stemming from the passing of legislation which removed longstanding forms of discrimination and widespread changes in social attitudes generally. By 2018 there were significantly fewer lesbian groups and organisations than in the earlier period. Legal changes meant that a number of women were living within their family systems and no longer appeared to need lesbian groups as support or for socialising. However, new groups did also form, often covering or formalising new areas of activity.

A number of law reforms improved the lives of lesbians over this period. The Human Rights Act 1993 consolidated and amended the Human Rights Commission Act 1977, adding five new prohibited grounds of discrimination, including sexual orientation. Introduced by Katherine O’Regan, National MP for Waipa, the term ‘lesbian’ was specifically added to the definition of sexual orientation.

Changes to immigration policy from 1991 allowed same-sex partners to gain residence. The Civil Union Act 2004 allowed same-sex legal partnerships. The Relationships (Statutory References) Act 2005 provided legal consistency for same-sex couples. The Births, Deaths, Marriages and Relationships Registration Amendment Act 2008 allowed both lesbian mothers and their partners to be named on the birth certificates of their children, whether conceived through assisted reproductive technology or donated sperm. Finally, the Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Act 2013 allowed same-sex couples to marry.

Thus, by the early 2000s, more women could live public lesbian lives, including living openly with women partners and raising children in lesbian households. After same-sex marriage was legalised, married lesbian couples could adopt jointly; but for those in de facto relationships or civil union partnerships, only one partner could adopt, while the other partner could become a guardian. Single people could also adopt (subject to the restrictions in the Adoption Act 1955).

Changes also occurred because of the development of the internet, which improved possibilities for lesbians to meet and communicate. National and local websites, as well as international websites, offered chat rooms. [11] Local web pages were set up for Wellington, Palmerston North, Hamilton, and Hawke’s Bay. [12] Other lesbian organisations formed for specific groups, including the Auckland Lesbian Business Association (ALBA) [13] and groups for lesbian elders. [14] Lesbian Studies courses continued to be taught in the Women’s Studies Programme at Victoria University of Wellington, at Nelson Polytechnic, and in other programmes; these courses became more general in the twenty-first century. Well-attended Lesbian Studies Conferences were held in Wellington in 1994 and 1995.

Prue Hyman.

Prue Hyman (right) taking part in Pride 2018 to promote Wellington Lesbian Radio, which has been broadcasting on Wellington Access Radio since 1984.

National news for lesbians became available at Lesbian News Aotearoa, the national online daughter of the Tāmaki Makaurau Lesbian Newsletter, published monthly in Auckland from September 1990. [15] The Lesbian Community Radio Programme in Wellington also set up its own internet site. [16]

A wide range of local lesbian groups also formed, including book groups, walking groups, such as the Wellington-based Lesbian Overland and Café Group, and potluck dinner groups, such as one on the Kāpiti Coast, plus regular events in Dunedin, Nelson, Whāngārei and other towns. Information about these activities was made available through lesbian internet sites.

In the twenty-first century, many younger and some older lesbians were choosing to join mixed groups or organisations, some under the umbrella term LGBTIQQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, questioning). Some preferred to identify as 'queer' and attend regular events held by Rainbow Wellington and other mixed organisations. Other mixed groups included choirs, such as Gay and Lesbian Singers (GALS) in Auckland [17] and the Glamaphones in Wellington [18], which were popular among many lesbians. Mixed public events attended by lesbians included Wellington’s annual Out in the Square, Auckland’s Hero Parade, and Pride parades and events in a number of other towns. Numbers of Māori women identified as takatāpui, and joined Tiwhanawhana in Wellington [19] and other takatāpui Māori organisations.

Lesbian history became better recorded after 1993. LAGANZ, the Lesbian and Gay Archives of New Zealand, housed at the Alexander Turnbull Library, preserved the histories of earlier lesbian groups and organisations. Their collections covered manuscripts, oral histories, memorabilia and published materials, including newsletters and magazines. Oral histories included the Club 41 project, with interviews from some of the founders and those who frequented this first Wellington lesbian club (1973–1977); and the Amazons project, with interviews from lesbians who played softball for this Wellington lesbian sports club (1977–2011).

Lesbians also began collecting their own archives. One significant new national organisation was LILAC, the Lesbian Information, Library and Archives Centre in Wellington. [20] Established in 1994, with centrally located premises and regular opening hours, it assembled a collection of lesbian literature and DVDs, and held events such as book launches and talks. In addition, Dr Miriam Saphira, Nicola Jackson and Christine Hammerton established the Charlotte Museum, Auckland, in 2007. It too opened its own premises with regular opening hours, preserved lesbian artefacts, books, magazines, manuscripts and oral histories, mounted exhibitions, and hosted other special events. [21]

Another important organisation began in 2001. The Armstrong and Arthur Charitable Trust for Lesbians, the first such organisation for lesbians in Aotearoa, was established by Bea Arthur (1915–2002), to assist lesbian community groups in the Wellington region. The Trust was named for Bea and her partner of 57 years, Bette Armstrong (1909–2000). It funded various lesbian projects and activities in Wellington, including the Lesbian Community Radio Programme Programme, LILAC, art exhibitions, theatre performances, and lesbian dance competitions. [22]

The archival collections, websites, and written histories, such as this publication, ensure that knowledge about past lesbian organising remains accessible to women in future years. Should the future bring a range of new circumstances requiring specific lesbian organising, it could thus be informed by knowledge of the past.

Notes

[1] There is little agreement about what the term 'lesbian' denotes. In this essay we define lesbians as women whose primary commitments and emotional/physical relationships are with other women. For further discussion, see Lillian Faderman, Surpassing the love of men: romantic friendship and love between women from the Renaissance to the present, William Morrow, New York, 1981; Sheila Jeffries, 'Does it Matter if They Did It?', in Lesbian History Group (eds), 1989; and Liz Stanley, 'Romantic Friendship? Some Issues in Researching Lesbian History and Biography', Women's History Review, Vol. 1 No. 2, 1992. This 1993 essay was far from exhaustive, and much research remains to be done. Not all of the material we had access to or knowledge of could be included. We would like to thank all lesbians who contributed to and assisted with this project.

[2] Anon., song lyric, c. 1990.

[3] Royal Commission on Social Policy, 'Women and Social Policy Part I - Māori Women', Section 2.2.38, The April Report, Volume II, 1988, p. 167.

[4] See BNZW, pp. 90-93. Such 'passing' continued into the early twentieth century.

[5] See Glamuzina and Laurie, 1991, Chapter 10; and Julie Glamuzina, 'Purple Hearts', in McPherson et al. (eds), 1992, pp. 100-111.

[6] See Glamuzina and Laurie, 1991, p. 158.

[7] See Andrea Weiss and Greta Schiller, Before Stonewall: the making of a gay and lesbian community, Naiad Press, Tallahassee, 1988.

[8] See Lesbian Feminist Circle, Nos 26 and 27, 1978.

[9] See Glamuzina and Laurie, 1991, for a full discussion of homosexuality and the law in New Zealand.

[10] Lesbians with disabilities became the target of an ill-informed media campaign following the Ministry's attempt to survey services available to them through disability organisations. See Chris Atmore, 'Out of Reality: The Media and Disabled Lesbians', Sites, No. 19, Spring 1989, pp. 76-95.

[11] For example, Lesbian Aotearoa New Zealand at http://www.lesbian.net.nz and NZ Lesbian Community Site at http://lesbian.co.nz/

[12] http://wellington.lesbian.net.nz/; https://www.malgra.org.nz/ (Palmerston North); http://www.decodivas.co.nz/ (Hawke’s Bay).

[13] http://www.alba.org.nz/;

[14] For example, Lesbian Elders Village

[15] https://lesbianaotearoa.wordpress.com/about/

[16] http://wellington.lesbian.net.nz/radioshow.html

[17] gals.org.nz

[19] http://www.tiwhanawhana.com

[20] https://lilac.lesbian.net.nz/

[21] http://charlottemuseum.lesbian.net.nz

[22] http://www.armstrong-arthur-trust.nz

Unpublished sources

Charlotte Museum, Auckland

Lesbian and Gay Archives of New Zealand (LAGANZ), ATL

LILAC, Lesbian Information, Library and Archives Centre, Wellington

Waxing Moon collection, LAGANZ (formerly in possession of Zoe Windeler, Hamilton)

Published sources

Circle, 1973-1974; Lesbian Feminist Circle, 1974- 1985

Du Plessis, Rosemary et al. (eds), Feminist voices: Women's Studies texts for Aotearoa/New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Auckland, 1992

Faderman, Lillian, Odd girls and twilight lovers: a history of lesbian life in twentieth century America, Columbia University Press, New York, 1991

Glamuzina, Julie, Out front: lesbian political activities in Aotearoa, 1962-1985, Lesbian Press, Hamilton, 1993

Glamuzina, Julie and Alison Laurie, Parker and Hulme: a lesbian view, New Women's Press, Auckland, 1991

Hall, Sandi, 'A Different 10 Years', Broadsheet, No. 101, July/August 1982, pp. 42-45

Jackson (Saphira), Miriam, 'Should Feminists Support Gay Men?', Broadsheet, No. 80, June 1980, pp. 32- 33

Laurie, Alison, 'Lesbian Worlds', in Cox (ed.), 1987, pp. 143-56

Laurie, Alison, 'Lesbianism—a Review of Oppression', Sites, No. 15, Spring 1987, pp. 59-67

Laurie, Alison, 'Katherine Mansfield—A Lesbian Writer?', Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 4 No. 2, December 1988, pp. 48-69

Laurie, Alison, ‘From Kamp Girls to Political Dykes', in Julia Penelope (ed.), Finding the lesbians, Crossing Press, New York, 1990, pp. 69-84

Laurie, Alison J., ‘ Filthiness became a theory: an overview of homosexual and lesbian organising from nineteenth century Europe to seventies New Zealand’, in Alison J. Laurie and Linda Evans (eds), Outlines: lesbian and gay histories of Aotearoa, LAGANZ, Wellington, 1993, pp. 10-18

Laurie, Alison J. (ed.), Lesbian Studies in Aotearoa/New Zealand, The Harrington Park Press, New York, 2001

Laurie, Alison J., ‘”We were the Town’s Tomboys”, an Interview with Raukura ‘”Bubs”Hetet’, Journal of Lesbian Studies, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2010, pp. 381-400

Laurie, Alison J., ‘Lesbian Nation in Aotearoa/New Zealand’, Sinister Wisdom, No. 70, 2007, pp.27-33.

Lesbian History Group (eds), Not a passing phase: reclaiming lesbians in history, 1840-1985, The Women's Press, London, 1989

McPherson, Heather et al. (eds), Spiral 7: a collection of lesbian art and writing from Aotearoa/New Zealand, Spiral, Wellington, 1992

Rankine, Jenny, 'Dykes in the Dailies', Broadsheet, No. 174, December/January 1989, pp. 27-31

Rankine, Jenny, ‘Lesbians in Teaching’, Broadsheet, No. 133, October 1985, pp. 26-28

Rosier, Pat, 'The Only Ones?' Broadsheet, No. 153, November 1987, pp. 24-29

Saphira, Miriam, Amazon mothers, Papers Inc., Auckland, 1984

Smith, Jan, 'Lesbianism and Mental Health', Broadsheet, No. 53, October 1977, pp. 18-21

Te Awekōtuku, Ngāhuia, Tahuri, New Women's Press, Auckland, 1989

Te Awekōtuku, Ngāhuia, Mana wāhine Māori: selected writings on Māori women's art, culture and politics, New Women's Press, Auckland, 1991