Coalition for Equal Value Equal Pay (CEVEP)

1957 –

Theme: Employment

Known as:

- Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity (CEPO)

1957 – 1977 - Coalition for Equal Value Equal Pay (CEVEP)

1987 –

This essay written by Margaret Hutchison was first published in Women Together: a History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Linda HIll in 2018.

1957 – 1977

The aims of the Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity (CEPO) were 'to bring about as soon as possible the full implementation of the principles of equal pay for equal work (or the rate for the job) and equal opportunity for women in all spheres of employment in New Zealand'. [1] Its membership included major unions, especially the North Island Electrical Workers' Union, the New Zealand Federation of University Women (NZFUW), the Māori Women's Welfare League, the National Council of Women (NCW), the New Zealand Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs (NZFBPW), and the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

In 1956 the Public Service Association had been involved in sometimes bitter disputes with the Public Service Commission and the government over the employment conditions – particularly pay and promotion – of its women members. In November that year the PSA equal pay committee called a meeting of representatives of women's organisations and trade unions to discuss forming a national body to work toward equal pay in both the public and private sectors. Dan Long, PSA secretary and convenor of the committee, pointed out the need for research into New Zealand and overseas experience of equal pay, and also the value of co-ordinating the activities of organisations concerned.

Those attending agreed to take the proposal back to their parent organisations. A further meeting on 10 April 1957 formally established the Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity, and adopted the constitution drafted by Long and Patricia Webb of the NZFUW. Each member organisation was entitled to two representatives on the council. The first president was Challis Hooper, a retired nurse connected with both the YWCA and the NZFBPW; Margaret Brand (later Long), an activist in the PSA's equal pay campaign, became its first secretary. The PSA offered the use of its meeting room and office services.

The council began by organising a series of talks on the social, financial and industrial implications of implementing equal pay in New Zealand. These were then circulated among members for further study. As 1957 was a general election year, CEPO concentrated on writing to political parties, asking questions at candidates' meetings, and issuing press statements. Although the Labour Party in opposition had expressed support for equal pay, it proved less enthusiastic when in office. So for the next three years, led by its second president Grace du Faur, CEPO lobbied politicians, produced pamphlets and generally created maximum publicity, with women's organisations and trade unions working in close co-operation.

When the Government Service Equal Pay Act was finally passed in 1960, many people expected that equal pay would automatically extend to the private sector. While CEPO kept a sharp eye on the public service, trade unions pushed for progress toward equal pay in their awards, and also took cases to the Arbitration Court. But it soon became obvious that this was not sufficient.

In the early 1960s, CEPO struck trouble. Du Faur had moved to Tauranga; Brand had married Dan Long in 1960 and resigned in 1962. Her successors had not stayed long in Wellington, and Olive Smuts-Kennedy, the next president, found it impossible to combine that role with being the secretary too. The publicity programme and series of articles for trade union journals planned for 1963 lapsed, and CEPO was in danger of disintegrating. After Smuts-Kennedy resigned in December 1965, vice-president George Hobbs carried on until the November 1966 AGM, when Rita King of the Wellington BPWC became president. A qualified accountant, she had been a staunch supporter of equal pay for many years, and had recently resigned as chief accountant to a large commercial organisation following her marriage. For the next six years she devoted her time, energy and ability to CEPO. Under her leadership the council reactivated its quarterly meetings, with speakers and study themes, designed and distributed new pamphlets, again lobbied politicians, asked questions of candidates at election times, and supported and followed up trade union initiatives.

CEPO's constitution was amended in November 1968 to provide for district committees, which would promote the council's aims within their own area. Committees established in Auckland and Christchurch generated further publicity, with Auckland secretary Connie Purdue of the Clerical Workers' Union proving a particularly effective campaigner.

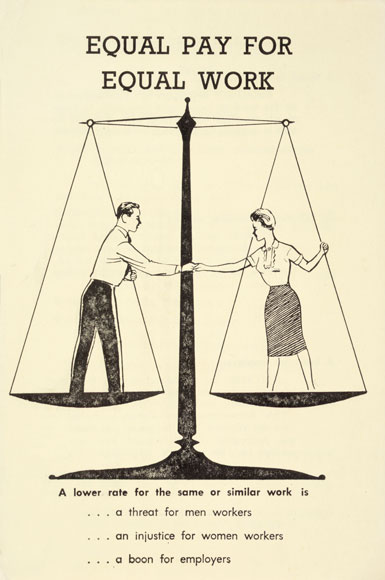

Cover of the Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity’s first national newsletter, April 1969. (ATL, Eph-A-WOMEN-1961-01)

The government set up a commission of inquiry in 1971 to report on 'how best to give effect in New Zealand to the principle of equal pay for male and female employees'. [2] The five-person commission included one woman, Miriam Dell, a member of the CEPO executive. CEPO made submissions to the commission and to the select committee on the Equal Pay Bill the following year; both were written and presented by King.

In 1972 the Equal Pay Act was finally passed; equal pay was to be introduced in approximately five equal steps, so that by 1 April 1978 there would be one rate of pay for all workers employed in any one job. The council promptly issued a pamphlet for women explaining the Act and their rights. It also set up five sub-committees – Education, Watchdog, Publication, Opportunity and School Curriculum – to monitor the progress of the Act and promote the idea of equal opportunity.

In 1977, when equal pay was supposed to be a reality, the second of the council's two aims was also apparently won with the passing of the Human Rights Commission Act, which outlawed discrimination in employment on the grounds of sex. Soon afterwards, the district committees disbanded, and the parent council went into recess.

1987 – 1993

In 1987, after an adverse ruling by the Arbitration Court in 1986 revealed inadequacies in the legislation, CEPO was revived. With Elizabeth Orr as president and Margaret Long returning as a vice-president, the council joined the Coalition for Equal Value Equal Pay (CEVEP) in a strong campaign for an Employment Equity Act. The legislation was passed by the Labour government in 1990, but was repealed later that year following a change of government.

In the 1990s the council was waiting to see what effect the Employment Contracts Act would have on women's wages, and was ready to revive the campaign for equal pay and employment opportunity should the need arise.

Margaret Hutchison

1994 – 2018

After repealing the Employment Equity Act in 1990, the National government established an EEO Trust to encourage private sector employers to adopt equal employment opportunity policies. However, women within opposition political parties continued to work towards strong pay equity policies. When a Labour/Alliance coalition won the 1999 election, discussion documents and a taskforce led to the setting up of a Pay & Employment Equity Office and a programme of pay reviews across the public service, health and education.

Part of this policy approach was a view that pay equity claims were not possible under the 1972 Equal Pay Act. CEVEP, including CEPO, disagreed. It successfully lobbied women MPs and others not to proceed with a 2004 bill, which would have repealed the Equal Pay Act and shifted equal pay for women and men in the same job to the personal grievance section of the Employment Relations Act. This would have meant that there was no longer any legislation on equal pay for work of equal value in jobs done exclusively or predominantly by women, as required by international conventions.

In 2013 CEVEP’s position was vindicated when rest home caregiver Kristine Bartlett and the Service & Food Workers Union (which became E Tū) took a successful pay equity test case. [3] CEVEP assisted the Employment Court as an ‘intervening party’. By then CEVEP had become a small expert group, part of a wider union-led Pay Equity Coalition (PEC) with hubs in Wellington, Auckland and other centres.

The next stage of court action was sidestepped by the then National-led government establishing a joint working group of unions and employers led by the State Services Commission to develop pay equity principles. Women’s organisations were excluded, but made written submissions. A second joint working group was established to negotiate Bartlett’s claim. Although no detailed gender neutral job evaluations were undertaken, her work and pay were broadly compared with 14 male-dominated jobs in the health sector, Corrections and Customs. The eventual outcome was substantial pay equity increases for more than 55,000 rest home, health and disability carers and 5000 mental health carers, to be implemented over five years. A series of other pay equity claims were also lodged.

In 2017 CEVEP, as well as PEC, other women’s organisations and the unions, lobbied against a bill drafted by the National-led government that would have undermined the new case law. Although it briefly became law in late 2017, it was immediately repealed when the political parties that opposed it won power and formed a new Labour-led government. In 2018 this government consulted women’s organisations, including CEVEP and PEC, on pay transparency issues, and began working on updating the Equal Pay Act, with a Bill expected in late 2018.

Linda HIll

Notes

[1] Constitution of Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity, p. 1.

]2] Commission of Inquiry into Equal Pay: Terms of Reference, Government Printer, Wellington, 1971, p. 5.

[3] The Employment Court judgment in Bartlett & SFWU v Terranova Homes & Care [2013] NZEmpC 157 was ‘a clear and strong ruling that claims for equal pay for work of equal value can indeed be made under the Equal Pay Act’ (Hill, 2013, p. 27). The Court also stated that, in order to identify male comparators whose rate of pay was unaffected by discrimination in female-dominated workplaces or sectors, ‘it may be necessary to look more broadly, to jobs to which a similar value can be attributed using gender neutral criteria’ (cited Hill, 2013, p. 27). When Terranova appealed, the Appeal Court confirmed the first judgment. Terranova’s attempt to appeal to the Supreme Court was rejected. The government set up the Joint Working Group, negotiations followed, and legislation was passed so that the new pay rate won by Bartlett would apply to all employers of residential carers. The new pay scale began on 1 July 2017.

Unpublished sources

Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity records, 1956–1970, Dan Long Union Library, PSA, Wellington

Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity records, 1971–1977, 1987–1992, NZEI Library, Wellington

Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity, Auckland branch records, 1969–1977, ATL

Rita King papers, in possession of Elizabeth Orr, Wellington

Published sources

CEVEP, Kristine Bartlett and Service & Food Workers Union vs. Terranova Homes & Care Ltd, July 2017, accessed 17 July 2018: http://cevepnz.org.nz/What's%20happening/Bartlett%20vs%20Terranova.htm

Hill, Linda, ‘Equal pay for equal value: The case for care workers’, Women’s Studies Journal, Vol. 27 No. 2, December 2013, pp. 14–31, accessed 17 July 2018: http://www.wsanz.org.nz/journal/docs/WSJNZ272Hill14-31.pdf

Community contributions